MLK Day 2016: Black Economic Justice Agenda Inspired By Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People's Campaign Lives On

Janae Bonsu is a great admirer of the Rev. Martin Luther King, but the allure has less to do with the civil rights icon's renowned legacy of nonviolent activism and seeking a measured compromise with white oppressors. Instead, Bonsu gravitated to a different, yet related sentiment often overlooked when remembering King: “We are struggling now for genuine equality,” King said in 1968. “It's much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good, solid job.”

King, late in his 39 years of life, was working to empower blacks and the poor through the redistribution of wealth, something that Bonsu, a 24-year-old community organizer from Chicago who is African-American, has been particularly inspired by. “I’m really about uplifting radical King, who was focusing on the most marginalized,” Bonsu said days before she and a group of black youth around the country unveiled a similar economic justice initiative this past weekend for King's birthday and ahead his national holiday Monday. Their platform, dubbed the “Agenda to Build Black Futures,” builds on an idea that has been diluted in the years since King was killed.

Nearly 50 years after King launched the Poor People’s Campaign, which posited that economic justice was needed in order to cure racial inequality in the U.S., the economic gap between black Americans and their white counterparts remains sizable. Some of today's young activists protesting under the law enforcement reform-focused Black Lives Matter banner are hoping to revive King’s economic agenda that seeks jobs and labor rights for the black working class and dismantles government-supported institutions -- such as private prisons -- that have disproportionately affected blacks. While street-level protests will continue, the messages will be more nuanced, they said.

“We’re not just bodies at a rally, and we’re not just angry with protest signs,” said Bonsu, who is national public policy chair for the Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100), a national grassroots social justice organization. “We’re trying to pick up on what we see as an unfinished economic agenda.”

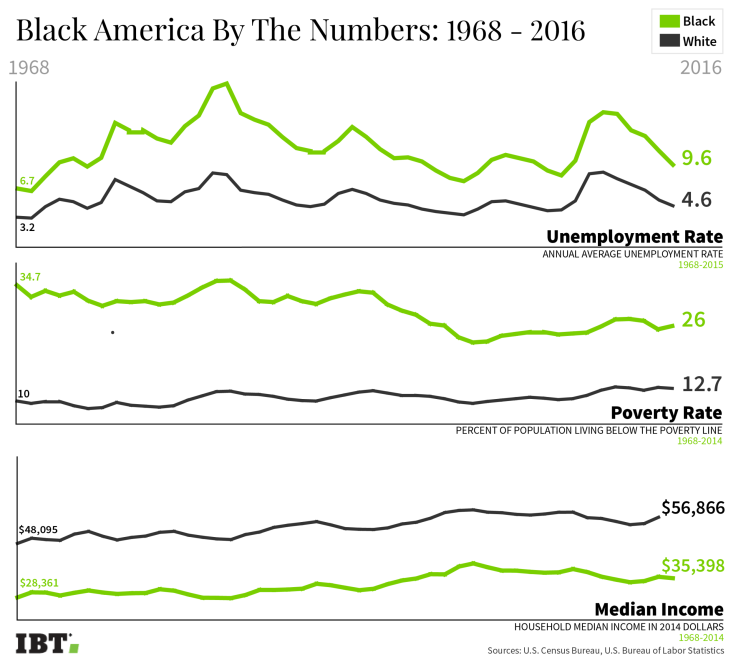

Black-white socioeconomic disparities have existed since U.S. slavery was abolished in the 19th century, but economists and activists have in recent years decried the widening or unchanging gaps between the white haves and the black have-nots. Data from the U.S. census and labor statistics bureaus reveal a particular narrative:

Even after the country climbed out of its worst economic downturn since the Great Recession a few years ago, the African-American unemployment rate stood at 8.3 percent in December, nearly double the white rate of 4.5 percent. The gap is even wider for black youth, compared to white youth, while the median income for black households was $35,398 -- almost half the white household median income of $60,256 -- in 2014.

Data on national poverty present a more troubling picture for young Americans. In 2014, there were 46.7 million people in poverty -- a term denoting annual cash earnings of $23,283 or less for a family of four. That’s about 14.8 percent of the nation’s estimated 319 million residents.

But blacks, who make up nearly 14 percent of the U.S., were lopsidedly impoverished at a rate of 26 percent, or 10.7 million people, in 2014. Whites, who are 62 percent of the U.S., were in poverty at a rate of 10 percent, or 19 million people. However, in the last couple of years, the poverty rate increased for college-educated people aged 25 and older, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“The American Dream of meritocracy has never guaranteed prosperity for black people in America,” Charlene Carruthers, BYP100 national director, wrote in the foreword of the group’s 44-page report that International Business Times reviewed ahead of its full release in February. “When added together, all black households own only a small fraction of overall wealth in the U.S., despite the fact the unpaid labor of our ancestors created the basis for much of that wealth,” Carruthers said.

The Agenda to Build Black Futures is a multipronged approach to socioeconomic justice that describes the condition of poverty as a form of violence against blacks, and reparations as a prescription for social ills, among other proposed structural changes. But the word “reparations” here isn’t a throwback to the decades-old debate about repaying the descendants of victims of chattel slavery in the U.S.

BYP100 demands that federal, state and local governments compensate the black victims of historical wrongs, including the redlining that denied blacks quality housing next to whites, the war on drugs that decimated a generation of black potential, mass incarceration policies that disproportionately doles out harsher sentences to black offenders, and police violence that has taken an untold financial and psychological toll in communities of color. The money would help blacks start a holistic repairing of their lives, the group said.

The agenda doesn’t stop there. It also calls for adoption of a national black workers’ bill of rights, which include maternity and paternity leave, sick leave, protections against employment discrimination based on criminal record, anti-discrimination policies targeting transgender individuals, and erasure of pay disparities based on race and gender in public and private places of employment. In addition, government bodies must divest from corporations that support the prison-industrial complex, reduce police department budgets and end fee regimes for petty crimes, such as jaywalking or unkempt lawns, and justice system fines, like administrative costs for probation and parole.

Its release during the King holiday weekend is part of the “Reclaim MLK” movement launched last year by a coalition of social justice groups, including Black Lives Matter and the Dream Defenders, a Florida-based black liberation group. There had been a feeling among these groups that King’s legacy -- his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech -- had been co-opted and quoted by figures who support the institutions activists sought to dismantle.

If BYP100’s wide-ranging approach sounds familiar, it’s because Occupy Wall Street, the protest movement reacting to capitalist forces that caused the 2008 economic recession, had expressed similar ideas. But Occupy’s “lack of a message that centered the experiences of Black folks was a significant impediment” to the movement's longevity, the BYP100 wrote in its agenda report. “Economic justice and racial justice in the U.S. are inextricably linked, and neither can be won unless the struggles of young black people are centered,” the group said.

#BYP100 Demands that Chicago divest from police! #buildblackfutures #ReclaimMLK pic.twitter.com/Rrkw5nEMGD

— BYP100 (@BYP_100) January 16, 2016

The agenda is the product of work that BYP100 began during the 2013 trial of George Zimmerman, the Florida man acquitted of second-degree murder in the shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. Members of BYP100’s city chapters, which include those in Chicago; Oakland, California; Detroit; New Orleans; New York City; and Washington, D.C.; sought an economic justice and policy platform that complemented the protest movement that would become Black Lives Matter.

As a movement that grew rapidly in 2014 after the police-involved killings of unarmed black men in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, Black Lives Matter became a household name. Activists’ searing condemnation of police brutality incidents against blacks -- those caught on video and looped endlessly in national news broadcasts and on social media platforms -- permeated presidential politics and jump-started criminal justice reform efforts around the U.S. But some critics of the movement, which lacks a centralized leadership structure, pointed to the seeming absence of nuance and a specificity of solutions in some protesters’ message, which King’s Poor People’s Campaign had.

“What King was proposing to do was pretty audacious,” said Clayborne Carson, a historian who directs the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. “He was essentially getting people to occupy the National Mall indefinitely” until the federal government could agree to fund an end to poverty, he said.

King’s campaign was formed at a staff retreat of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights group, in November of 1967. The civil rights leader had expressed his concerns that desegregation and voting rights granted under the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 would not lead to true equality for minorities if they are always poorer than whites.

“Poor people’s lives are disrupted and dislocated every day,” King said in a campaign brochure published in the spring of 1968. “We want to put a stop to this. Poverty, racism and discrimination cause families to be kept apart, men to become desperate, women to live in fear, and children to starve,” he said.

The problem was sizable in 1968, the year of the Poor People’s Campaign launch. The national unemployment rate was 3.6 percent. But blacks were unemployed then at a rate of 6.7 percent, compared to the white rate of 3.2 percent. There were 35 million people considered to be impoverished, or earning less than $3,130 as a family of four, $21,346 when adjusted for inflation.

King was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968, after arriving there to support black sanitation workers who were striking over inequitable wages and benefits that were offered to whites. In the years that followed King’s death, the Blank Panther Party adopted some of the ideals that King had championed, such as the free breakfast program in urban black communities, but under a more militant banner espousing black nationalism. There was a feeling that the Poor People’s Campaign was too visionary for the contemporary political climate and that the civil rights victories already won by King and others needed preserving, said Carson, the King scholar.

Many young African-Americans have said King’s assassination and the government's targeting of the original Black Panther Party had much to do with their focus on economic justice. But that didn’t deter actions coordinated over the King holiday weekend, said Cynthia Malone, a New York-based member of BYP100.

“I think what excites me most about the agenda is that it’s smart, it’s intelligent,” Malone, 25, said Friday, the day activists in New York City kicked off King-related activities. “We’re not just talking about how black youth should think about their dreams, we’re actually laying out how a real set of goals and economic changes that would uplift all black lives,” she said.

Targeting political leaders who oppose their economic changes, street marches and sit-ins at offending institutions will follow a nationwide publicity campaign around the Agenda to Build Black Futures, Malone said. Activists were expected to hold a “teach-in” Monday afternoon at the Ya-Ya Network headquarters in Manhattan.

“We’re just trying to educate and bring black people into a greater realm of knowledge and acknowledging what Dr. King actually stood for,” Malone said. “Dr. King’s vision was radical.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.