More Than Half Of All Mega-Mergers Disappoint Investors. Why Are They Booming?

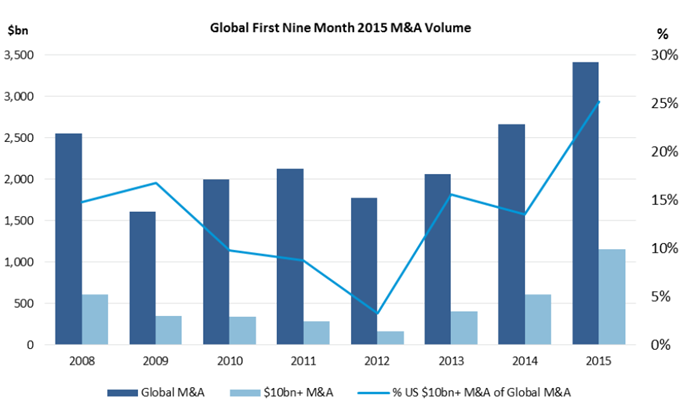

Anheuser-Busch InBev's massive deal to acquire SABMiller would bring 30 percent of the world’s beer market into one firm and comes in a year that is on track to rival 2007 for the highest value of mergers and acquisitions on record. But as CEOs jostle to join the party, experts in dealmaking warn that success is hard to come by.

“More often than not, these things don’t deliver what people expected at the outset,” said Andrew Waldeck, a partner at the global consultancy firm Innosight.

Studies have shown that between 50 and 80 percent of all mergers miss the marks set by management. It’s a sobering track record for a field that is expected to see a record $4.7 trillion in global dealmaking, driven in part by a narrowing window for accessing cheap credit before the Federal Reserve lifts interest rates from zero.

As management teams rush to enter the market for fear of missing out on the next great deal, the likelihood of poor decisions increases. And for every blockbuster merger, the evidence suggests there is at least one dud. The dismal experiences of DaimlerChrysler and AOL-Time Warner, for instance, still weigh heavily on investors’ minds.

Leverage vs. Reinvention

But not all mergers are the same.

Waldeck explains that companies seek out strategic acquisitions for two basic reasons. On one hand, a firm might pick a suitor whose qualities complement its existing business model. That could mean expanding into new geographies or buying a firm that represents a link in the supply chain. In a 2011 Harvard Business Review article, Waldeck and his coauthors called that strategy “leverage my business model.”

The deal between AB InBev and SABMiller -- the top two beer manufacturers in the world -- falls largely into this category.

AB InBev press materials in advance of the deal’s announcement trumpeted the two companies’ “largely complementary geographical footprints and brand portfolios.” SABMiller has its roots in Africa, providing a foothold for InBev that the acquirer has called a “key piece” of the deal.

On the other hand, an acquisition may be more about reinvention. A company facing a transforming market environment may seek to remake itself through a deal that introduces a totally new business model. Or a successful firm could go out on a limb and seek to actively transform not just itself but the entire industry.

Of course, these two strategies carry divergent risks and rewards. Expanding your existing business might not generate enormous returns, but neither does it carry the risks of a complete reinvention.

Those latter deals, Waldeck said, have the potential of meeting managers’ soaring rhetoric but also a greater potential to fall short. “It requires the organization to throw out some of its historical success formula -- that’s incredibly hard to do,” Waldeck said.

In a deal that seems to align more with the reinvention model, the privately held computer maker Dell surprised the tech world this week with its $67 billion takeover of data storage company EMC, the largest tech deal ever.

Dan Bulens, CEO of the software company Unidesk, called the deal an “epic transaction” in an interview with the Boston Globe. Michael Dell, Bulens said, had reinvention in mind: “If he can pull this deal off, he will have remade Dell.”

Still, Waldeck said the majority of transactions that have taken place in 2015 fall on the side of building leverage rather than remaking a firm’s core model. That means diminished odds of outright failure, but less chance of success.

All About Strategy

A host of complications bedevil any proposed mega-merger, from forging cultural harmony between two disparate organizations to navigating complex antitrust regulations.

The latter concern is sure to prove an obstacle to the beer conglomerate, which will likely have to jettison its stake in MillerCoors to pass muster with U.S. regulators -- and that’s not to mention the Justice Department’s reported probe into AB InBev’s aggressive maneuvering in American beer-distribution markets.

Investors also may want to look at how executives are compensated to estimate how a deal will turn out. Multiple studies have found that executives compensated chiefly in stock options and incentive pay tend to pick deals that increase shareholder value. Though steep incentive pay has come under criticism for encouraging short-term thinking, investors often benefit when CEOs see an upside from a big deal.

At AB InBev, where executives receive fat stock packages, the stars may be aligned. But the messy process of joining two vast corporate empires has yet to begin.

In the end, Waldeck said, successful deals generally align with a company’s natural business style: “It all links back to strategy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.