Most People Think Native Ads Are Real Articles - And They Later Feel Duped: Study

The great hope for the future of online advertising -- whether you call it sponsored content, branded content, native advertising or "branded voices" -- faces a simple and daunting problem: How do you fool people into reading native ads without making people feel fooled? Despite the labels and bylines on native ads, most readers still think they are actual articles, a study by the content marketing firm Contently indicated. And those readers are not happy when they realize they've been duped.

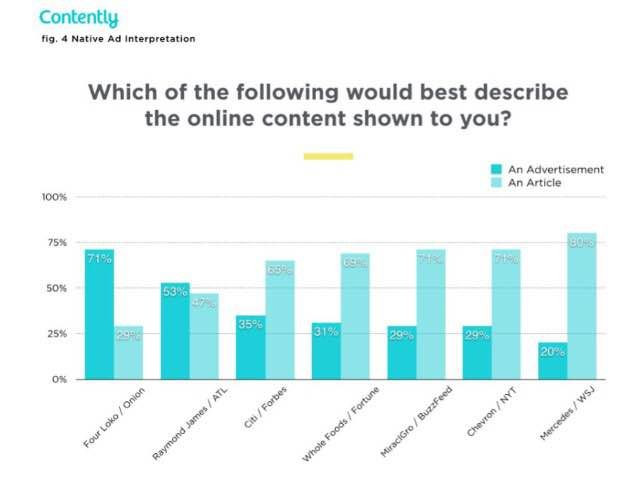

In a 10-minute online survey, Contently presented 509 consumers with native ads -- advertising dressed up as editorial content -- from BuzzFeed, the New York Times, the Atlantic, Forbes, the Onion and the Wall Street Journal. Respondents thought every ad was an article with the exception of the posts by the Atlantic and the Onion.

"On nearly every publication we tested, consumers tend to identify native advertising as an article, not an advertisement," the study said. Perhaps most surprisingly, an actual article from Fortune was less likely to be idenitified as a piece of editorial content than native ads from the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and BuzzFeed.

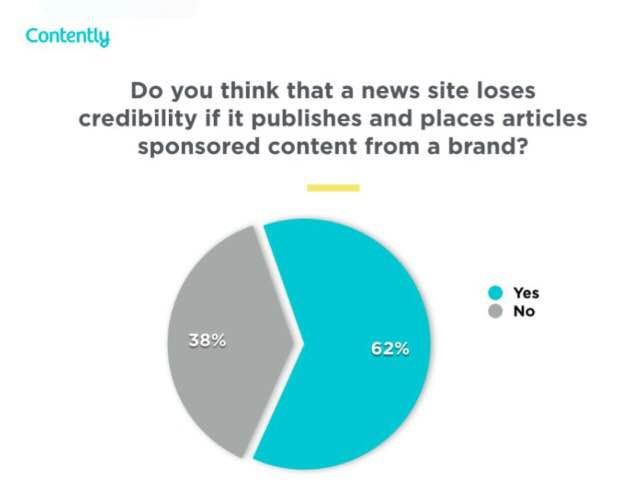

Another uncomfortable detail for publishers and brands: 62 percent of respondents thought a news site loses credibility when publishing native ads. That's up from 59 percent from a Contently study last year. Meanwhile, 48 percent felt deceived when they realized a piece of content was actually an ad they mistook for an article.

The study also found native ads aren't even that effective.

"Consumers often have a difficult time identifying the brand associated with a piece of native advertising, but it varies greatly, from as low as 63 percent [on The Onion] to as high as 88 percent [on Forbes]," it said.

To the critics of native ads, this seems to challenge the very premise of sponsored content -- if the ads don't blend in (some might say deceive), then what's the point? But Contently editor-in-chief Joe Lazauskas told International Business Times this argument ignores the potential of sponsored content to be neither deceptive nor ineffective.

"I question whether it’s valid that consumers won’t enjoy it if they know it comes from the brand," he said. "We do see Americans enjoy content from brands like Red Bull and American Express. They recognize its branded and enjoy it anyway."

He added sponsored content could still prove to be effective, arguing some publishers, such as BuzzFeed, have "shown progress on brand lift metrics, particularly for people repeatedly exposed to sponsored content."

Indeed, the minority of people who correctly identified the BuzzFeed post as an ad did rate it as a high-quality native ad. But that may suggest native ads work when executed in a certain way on certain sites, rather than working for all media and all brands across the board.

When asked why Contently -- a content marketing firm, after all -- took it upon itself to investigate the struggling state of native advertising, Lazauskas said the company wants to be as honest as possible about its business.

"We are invested," he said. "We do want to see the media world come to a better place where instead of intrusive, deceiving advertising, there’s good storytelling going on."

"At the same time we feel the responsibility to look into various issues that may not be helping to bring that world into fruition," he said. "If we can help guide everyone into better practices, that’s a win. If this study does help publishers find better ways to present native advertising, we will have contributed good to the media world we work in."

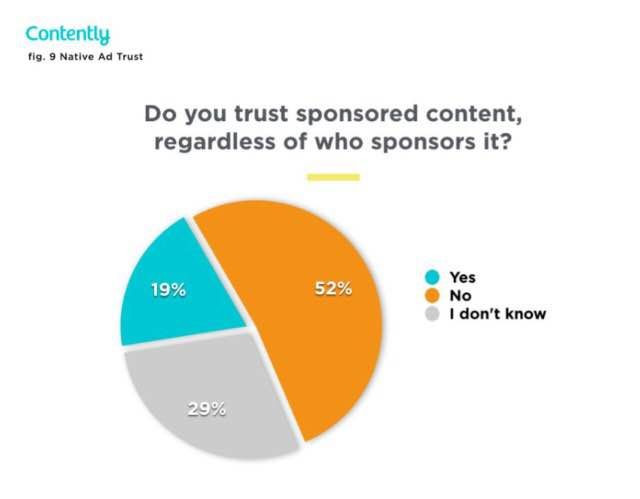

Lazauskas and the rest of the industry have some work to do. One more figure that sticks out in the study is the basis of the entire premise of sponsored content: trust. Fifty-two percent of respondents said that they don't trust sponsored content, regardless of who sponsors it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.