The Music Industry Has Had It With The Digital Millennium Copyright Act

The music industry is tired of playing whack-a-mole and is appealing to the U.S. Copyright Office and Congress to help. Hundreds of artists, managers and industry organizations signed petitions sent to the U.S. Copyright Office Thursday demanding reform of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, a law they say has placed undue burdens on them to scour the internet for people and websites illegally sharing their work.

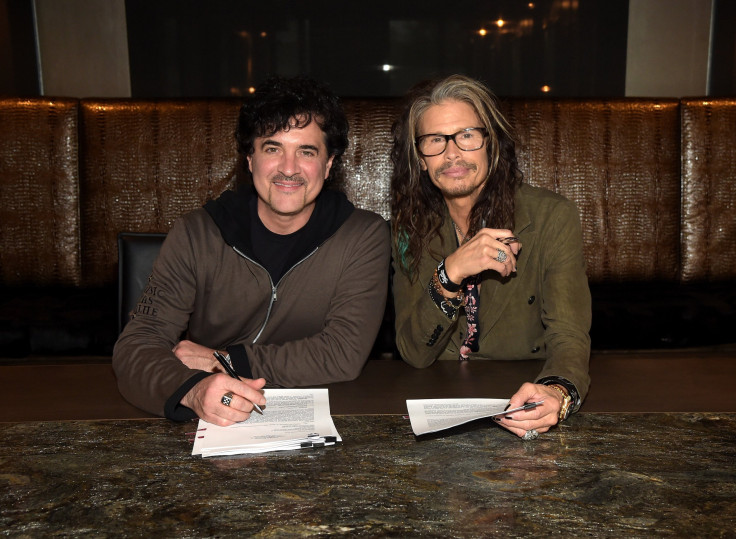

The signatories include current stars like Katy Perry and CeeLo Green, as well as iconic artists like Pete Townsend and Garth Brooks. It also includes every major music industry trade group and association, including the Recording Industry Association of America, the National Music Publishers Association and three of the biggest performance rights organizations. In addition to the petitions, the trade groups submitted a 100-page document outlining how they see the DMCA adversely affecting the industry.

“This law was written and passed in an era that is technologically out-of-date compared to the era in which we live,” one of the four petitions submitted reads. “It’s impossible for tens of thousands of individual songwriters and artists to muster the resources necessary to comply with its application.”

The Copyright Office had put out a public call for comments, the window for which closes Friday. While the Copyright Office does not have the authority to change the law on its own, it can make specific recommendations to Congress.

When the DMCA was signed into law in 1998, it was meant to keep the internet an open, innovative space where people could share information and content easily. Thanks to the law’s so-called “safe harbor” provision, websites were not responsible for figuring out whether content shared by their users or hosted on websites violated any copyright laws; they simply had to remove that content if they became aware that it did.

That provision, the music industry argues, essentially transferred the burden of detecting and thwarting copyright violations to copyright owners, a task that amounts to a full time job in and of itself. Today, there are now dozens of firms that exist purely to assist rightsholders in sending takedown requests to sites like YouTube and Tumblr.

Those firms have been kept busy. As the amount of content uploaded and shared on the internet has grown, the number of infringement notices sent by copyright owners has more than kept up. In 2012, Google alone received 54 million individual takedown requests. By 2014 that number had grown to 345 million, and this year, Google says, it has been receiving more than 17 million takedown requests per week.

Rightsholders and other artists claim this growth is proof of a dizzying responsibility that they cannot be expected to handle while continuing to make art. Yet other stakeholders frame that growth as proof the system is working.

The Computer and Communications Industry Association, a trade group that counts Google, Amazon and Yahoo among its members, filed its own comments on the DMCA this week making that exact point, saying filing takedown requests has grown easier, cheaper and more efficient.

“Takedowns are increasing because the system is effective,” Matt Schruers, the association’s vice president of law and policy, wrote in a blog post Thursday. “In short, the increasing use of takedowns shows demand for the DMCA. As notice volume increases, internet services build new tools to make it more efficient. That doesn’t mean that rightsholders are always accurate in their demands.”

The Copyright Office will hold additional hearings on the matter in Palo Alto and New York next month.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.