Musicians Behind Michael Jackson's 'This Is It' Sue Sony Entertainment, Claiming Wage Theft

Musicians who recorded tracks for a wildly successful concert documentary about Michael Jackson say Sony is illegally withholding hundreds of thousands of dollars from them.

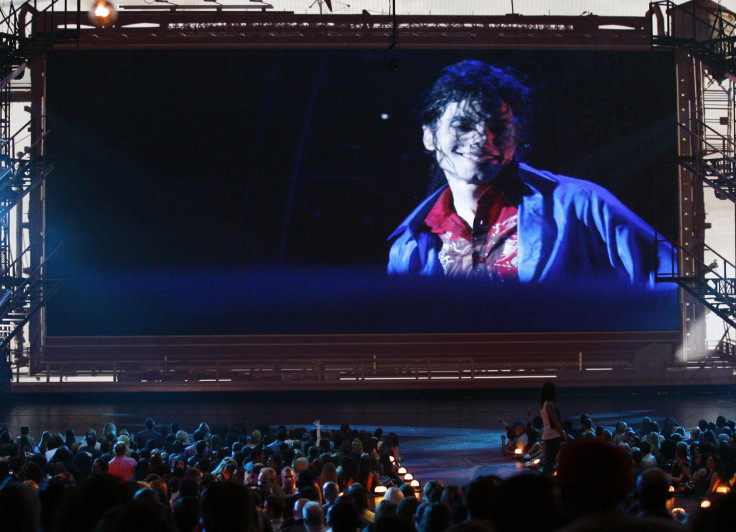

According to a complaint filed in federal court Tuesday, musicians recorded a session for Sony with the understanding their work would be used to enhance a bare-bones Michael Jackson demo from the early 1980s and would be released as a series of new, fully fleshed-out songs. The group of roughly 50 people -- including a 45-member chamber orchestra -- belongs to the American Federation of Musicians union and were paid according to the terms of a long-standing agreement with producers that covers sound recordings: anything from CDs and records to the digital files released through Apple’s iTunes. A month later, in October 2009, the song was released online. But then it appeared in an unexpected format, namely, the end credits of the Jackson concert documentary “This Is It.”

“I was kinda shocked,” says Jon Lewis when he heard the end credits of the film. “I thought something’s not right here.”

Lewis, 55, played trumpet in the September 2009 session for “This Is It” and has enjoyed a successful career in Hollywood, earning credits in scores and soundtracks for big-name titles such as “Star Trek” and “Spider-Man.” When he showed up to record “This Is It,” he says, all the musicians were told the tracks would not be appearing in the movie.

It sounds like a minor distinction, but that difference may have cost band members thousands of dollars each. The film’s worldwide gross revenue is $261 million.

A separate labor contract covers music that’s produced specifically for motion pictures, and it gives musicians a small share of the revenue that films generate over time after they leave theaters, usually around 1 percent. The sum is known as a residual wage, or a residual.

“A movie has a tail,” says Ray Hair, president of the musicians’ union. “Once it’s exited theaters, it has a long life span. You might see it on an airplane, on pay-per-view, then premium cable, then regular cable.”

The more it’s shown in these secondary markets, the more cash musicians get. “I would think this is a picture that’s going to be consumed across a lot of platforms for a long period of time,” Hair says. “What’s at stake here is the musicians’ share of that.”

But because the contract they recorded the music under doesn’t cover movies, musicians aren’t getting those additional payments. They say Sony’s cheating them out of money they’re owed: “It’s like, ‘Wait a minute, we fought hard for this 50 years ago.’ It’s not right for them to be screwing the contract,” Lewis says.

A Sony representative declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The complaint asks for an award of damages and any pay owed musicians. Union chief Hair says it’s hard to know what that amount could be, because Sony has refused to share information about the revenue the film has generated in secondary markets. Moreover, the revenue stream is ongoing. Lewis estimates he alone is probably owed several thousand dollars at this point.

In the same lawsuit, the union alleges Sony breached other, similar contractual obligations by failing to pay musicians for the “new use” of a number of other recordings: a Whitney Houston CD/DVD package, an Earth, Wind & Fire song that appears in the movie “The Intouchables,” a Tony Bennett album broadcast on TV, Pitbull's overdubbing of a Michael Jackson song and samples from the “This Is It” recording session that play in other portions of the documentary.

It’s not the first legal trouble for the song “This Is It.” Shortly after the track was released in 2009, songwriter Paul Anka told reporters he helped co-write the original song with Jackson and was exploring legal options. In that case, the Jackson estate quickly reached a settlement, naming Anka as co-author.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.