NASA Explains How Astronauts' Urine Is Turned To Drinking Water In Space Station

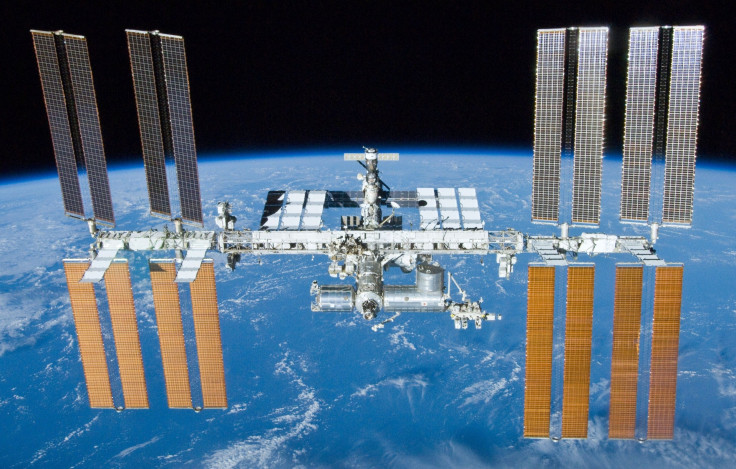

NASA officials recently discussed how the International Space Station (ISS) recycles the urine of its astronauts in a new podcast episode. Specifically, the NASA official explained how a piece of equipment aboard the ISS turns urine into drinkable water.

Inside the ISS, the survival of NASA astronauts largely depends on the systems around them. One of these is an equipment that can recycle liquids in order to turn them into safe, drinkable water. This is a vital component of the ISS since it ensures that the astronauts living on the space station always have water to drink.

Laura Shaw, the ISS’ program lead for Exploration Life Support Systems, recently explained how the station’s liquid recycling equipment works during the latest episode of NASA’s “Houston We have Podcast.”

Turning water into air & back into water (or yesterday’s coffee into today’s coffee) is all part of life on the @space_station. 💦 This week on our podcast, Laura Shaw describes how these systems work & improvements needed for future #Artemis missions. https://t.co/VyYe7vxBET pic.twitter.com/CJMt6eM5Zd

— NASA's Johnson Space Center (@NASA_Johnson) August 16, 2019

Speaking with the podcast’s host Gary Jordan, Shaw said that the space station has its very own urine processor that takes the human waste from the onboard microgravity toilet. Basically, what this does is it separates the water in urine through condensation. The extracted water is then processed further until it is safe to drink.

“It puts the urine on this surface of this rotating drum, that’s what the urine processor does,” Shaw said. “And then the heat makes it evaporate. And then we collect the humidity which is fairly clean at that point, not drinkable, but fairly clean.”

“We condense it and we send it to the next stage processor,” she continued. “The brine, which is the salts that are left behind, all the yucky stuff, we, right now put into storage containers.”

Shaw noted that after the extracted liquid goes through the next stage of the processer, it becomes drinkable.

Aside from urine, the ISS also uses other sources to make drinkable water such as humidity and sweat. Shaw noted that these other sources go through different processing methods in order to become drinkable water.

Although these systems already work fine, Shaw said that they can still be improved in order to become more efficient. NASA is hoping to use the improved versions of these systems for its future deep space missions.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.