NASA Explains What Happens When Two Black Holes Collide In Space

KEY POINTS

- Black holes are dense space objects with strong gravitational fields

- When two black holes collide, they eventually form a larger black hole

- There could be evidence of light being produced by a black hole merger

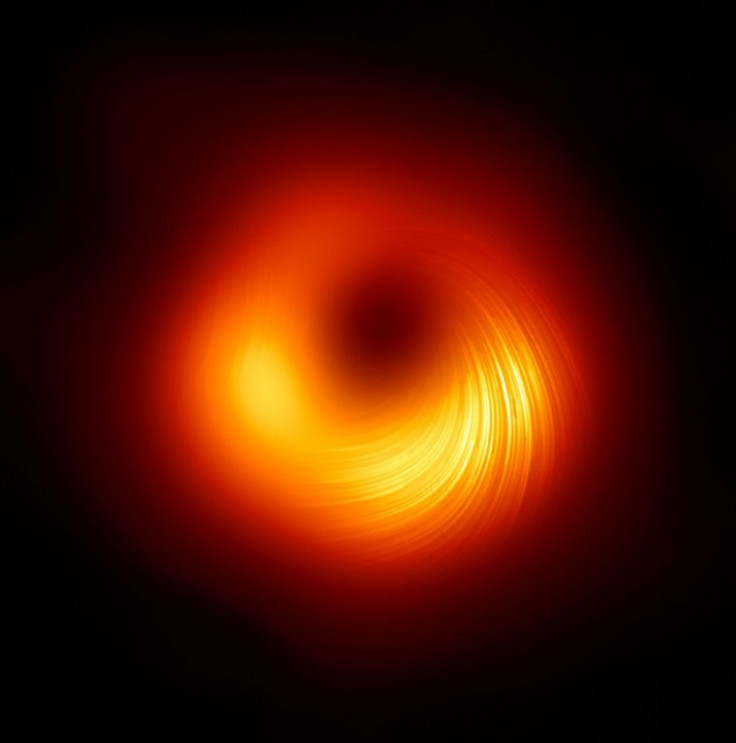

Black holes have been a source of constant wonder for many as there is so much mystery surrounding them. Contrary to what most may think, black holes are anything but space. Black holes consist of a colossal amount of matter packed into a very small area. This ultra-dense area then results in a gravitational field so strong that nothing can escape it -- not even light. But what happens when two black holes collide?

In a video posted by Simulating Extreme Spacetimes (SXS) Collaboration, a computer animation of a black hole merger explains how such an event occurs. The video features the final stages of a merger and highlights the effects that take place in the background starfield.

"The black regions indicate the event horizons of the dynamic duo, while a surrounding ring of shifting background stars indicates the position of their combined Einstein ring. All background stars not only have images visible outside of this Einstein ring but also have one or more companion images visible on the inside," NASA explains in the clip.

Eventually, the two black holes spiraling each other come together, forming an even larger black hole, as shown in the video.

In June of 2020, NASA astronomers reported about a merger that allowed them to detect light signals from two black holes. According to the site, when two black holes spiral around each other and ultimately collide, they send out gravitational waves or ripples in space and time that can only be detected by extremely sensitive instruments.

Because black holes and mergers are completely dark, these events cannot be seen with telescopes and other light-detecting instruments. However, scientists have come up with theories on how these mergers occur and how light can be produced by such mergers.

This theory was recently given possible evidence when scientists spotted what may have been such a scenario. The scientists made use of Caltech's Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) located at Palomar Observatory near San Diego. If confirmed, their observation would be the first known light flare from a pair of colliding black holes.

The results procured from the ZTF were detailed in the scientists' study published in the journal Physical Review Letters. In the study, the authors explained the possibility of two partner black holes orbiting a third black hole, which has a mass that is millions of times more than that of the sun. This supermassive black hole is surrounded by a disk of gas and other material, the scientists said.

The merger of the two smaller black holes then caused the formation of a new, larger black hole that shot off in a random direction, plowed through the disk of gas and caused it to light up.

"There's a lot we can learn about these two merging black holes and the environment they were in based on this signal that they are sort of inadvertently created," said Daniel Stern, co-author of the study and an astrophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

"The detection by ZTF, coupled with what we can learn from the gravitational waves, opens up a new avenue to study both black hole mergers and these disks around supermassive black holes," Stern added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.