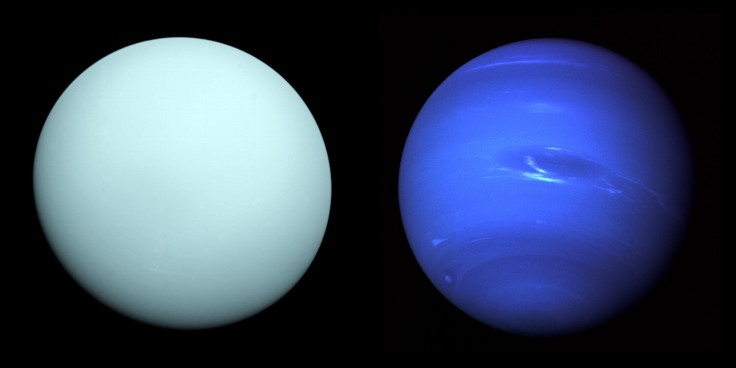

NASA Releases Uranus, Neptune Mission Concepts To Study Mysterious ‘Ice Giants’

Only one spacecraft in about 60 years of human space-faring, the Voyager 2, has ever come close to Uranus and Neptune, during flybys in 1986 and 1989 respectively. The comparative dearth of information about the two outermost planets in the solar system has long rankled astronomers and scientists, and to address that, NASA on Tuesday unveiled a study of future mission concepts that will explore the so-called “ice giants.”

Despite the colloquial tag used for them, Uranus and Neptune are thought to contain little solid ice now, though conditions could have been different at some point in the history of the solar system. The NASA study “identifies the scientific questions an ice giant mission should address, and discusses various instruments, spacecraft, flight-paths and technologies that could be used,” the space agency, which sponsored and led the study, said in a statement following its release.

Mark Hofstadter of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, one of the two co-chairs of the science team that produced the report, said in the statement: “This study argues the importance of exploring at least one of these planets and its entire environment, which includes surprisingly dynamic icy moons, rings, and bizarre magnetic fields.”

Read: Scientists Guess That Uranus Probably Smells Pretty Bad

The study discusses a number of possible missions that could study the strange worlds, including flybys, orbiters and probes. A probe could study the atmosphere of Uranus by diving into it, and a camera could take pictures of the planets and their many moons (Uranus has 27 moons we know of, while Neptune has 14).

“We do not know how these planets formed and why they and their moons look the way they do. There are fundamental clues as to how our solar system formed and evolved that can only be found by a detailed study of one, or preferably both, of these planets,” Amy Simon of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the other co-chair behind the study, said in the statement.

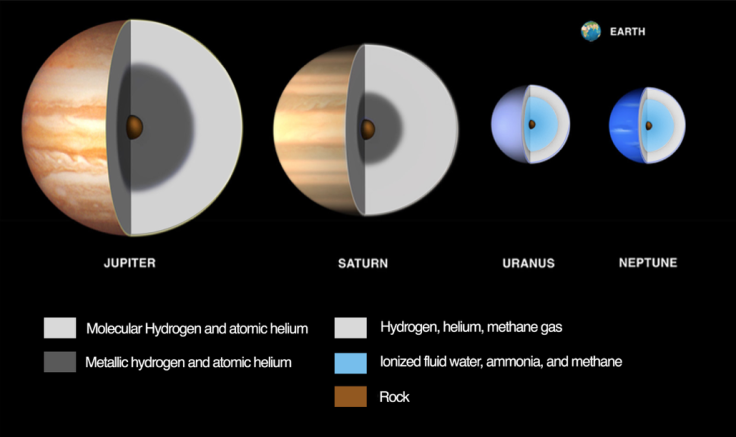

Compared to terrestrial planets like Earth and Mars, which are almost 100 percent rock, or the gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn, which are about 85 percent gas by mass, the ice giant planets are thought to have a sub-surface liquid ocean that accounts for about two-thirds of the planets’ mass. We do not know at present “how or where ice giant planets form, why their magnetic fields are strangely oriented, and what drives geologic activity on some of their moons.”

However, there are many exoplanets, orbiting stars outside the solar system, that appear to be similar to the ice giants we are familiar with. A month ago, scientists announced the discovery of a “warm Neptune” with a primitive atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. In March, a Neptune-sized planet was found in a star system 3,000 light-years away. And therefore, studying Neptune and Uranus could help improve our understanding of the universe, and how planets like them form.

The entire study (529 pages) can be found here, while a shorter executive summary is available here. The European Space Agency also participated in the study.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.