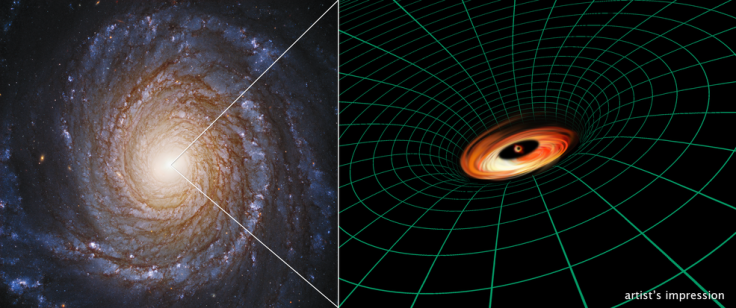

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope Detects Unexpected Black Hole In Spiral Galaxy

Using the NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers discovered a thin disk of material around a supermassive black hole in a galaxy about 30 million light years away.

The disk, however, should not be there because its presence defies current astronomical theories.

The black hole was found in the spiral galaxy NGC 3147. Black holes in these types of galaxies tend to be malnourished since there is not enough gravitationally captured materials to feed them regularly.

The researchers chose to study NGC 3147 to validate the models about lower-luminosity active galaxies which harbor starving black holes. The models predict that an accretion disk is formed when there is enough amount of gas that is trapped by the gravitational pull of a black hole.

This infalling materials emit lots of light, and in the case of well-fed black holes, produce a bright quasar. The quasar starts to break down and becomes fainter when there is less material being pulled into the disk.

The researchers were trying to confirm that the accretion disk does not exist anymore below certain luminosities, but instead, they found a disk normally seen in objects that are 1,000 or even 100,000 times more luminous.

Study researchers said that these observations failed predictions of current models for gas dynamics in very faint active galaxies.

“This result questions the very existence of true type 2 active galactic nucleus (AGN),” the researchers wrote in their study, which was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, which was published on July 11.

“Moreover, the detection of a thin disc, which extends below 100 rg in an L/LEdd ∼ 10−4 system, contradicts the current view of the accretion flow configuration at extremely low accretion rates.”

Using Hubble’s Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) to observe matter that swirl deep inside the disk, the researchers were able to observe dynamic processes close to a black hole. The researchers said that the discovery offers a unique opportunity to test Albert Einstein's theories of relativity.

“This is an intriguing peek at a disk very close to a black hole, so close that the velocities and the intensity of the gravitational pull are affecting how the photons of light look,” said study researcher Stefano Bianchi, of the Università degli Studi Roma Tre, in Rome.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.