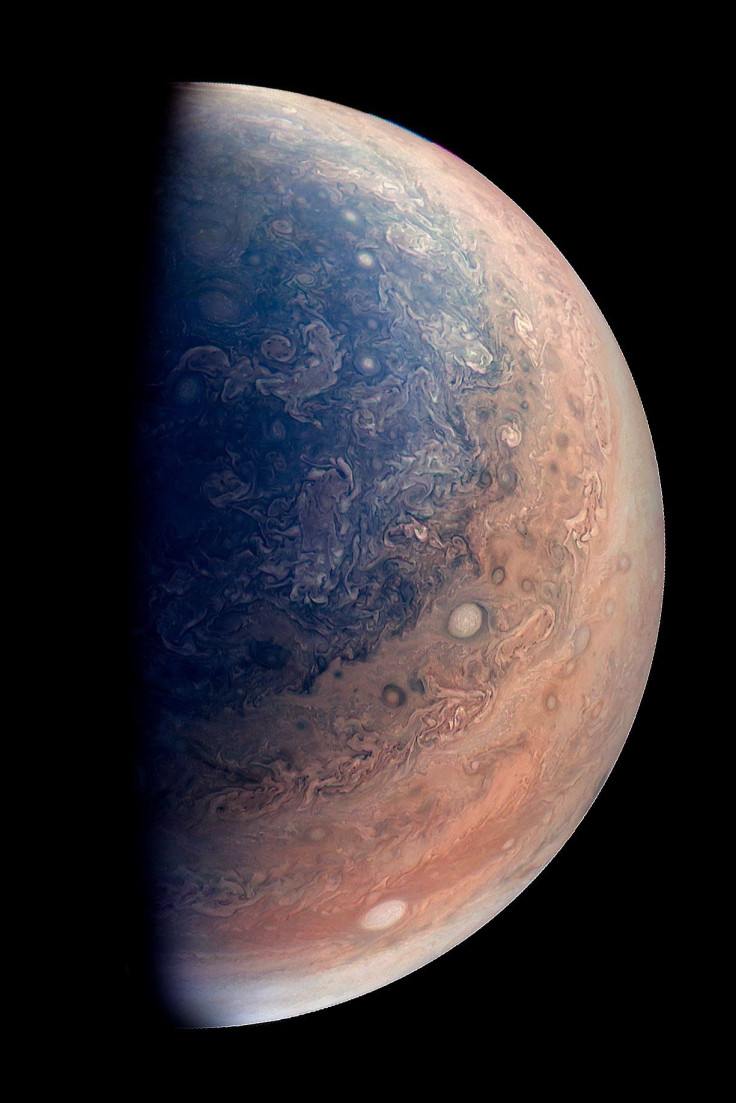

NASA's Juno Reveals Swirling Clouds And Giant Storms Over Jupiter's South Pole

The swirling cloud-tops of Jupiter have been revealed in their full glory in a new image snapped by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. The image, released by the space agency on Friday, was taken by the JunoCam instrument — a high-resolution color camera specially designed to work on a spinning spacecraft — from an altitude of about 32,400 miles above the gas giant’s atmosphere.

“This enhanced color view of Jupiter’s south pole was created by citizen scientist Gabriel Fiset using data from the JunoCam instrument on NASA’s Juno spacecraft,” the space agency said in a statement accompanying the image. “Oval storms dot the cloudscape. Approaching the pole, the organized turbulence of Jupiter’s belts and zones transitions into clusters of unorganized filamentary structures, streams of air that resemble giant tangled strings.”

Read: Hubble Snaps Stunning New Image Of Jupiter

A previous image of the south pole, captured when the spacecraft was roughly 58,700 miles above the polar region, shows that unlike the belts and zones found in the equatorial regions, the region is mottled by clockwise and counterclockwise rotating storms of various sizes.

Friday's photograph was released almost a year after Juno beamed back the first-ever images of Jupiter’s north pole — taken during the first of its three dozen flybys. The images, captured last August, show storm systems that are unlike anything seen on the other gas giants of our solar system.

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before,” Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a statement at the time. “It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to -- this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

Juno, which completed its most recent flyby of Jupiter (which was its fourth science orbit) on March 27, was launched in 2011. The primary goal of the mission is to investigate whether the biggest planet in the solar system has a solid core, and whether there is water in the planet's atmosphere.

So far, in addition to snapping stunning images of turbulent weather systems in Jupiter’s dense atmosphere, the solar-powered spacecraft has also revealed that the planet’s magnetic fields and aurora are bigger and more powerful than originally thought.

On the gas giant, solar winds carrying charged particles known as coronal mass ejections compress Jupiter’s magnetosphere, shifting its boundary inward by more than a million miles. This gives rise to energetic X-rays in Jupiter’s aurorae, which cover an area bigger than the surface of Earth.

Juno’s next close flyby is scheduled for May 19.

“Juno is providing spectacular results, and we are rewriting our ideas of how giant planets work,” Bolton said in a statement released in February.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.