NASA’s New Horizons Spacecraft Leaves Hibernation To Perform Historic Deep-Space Flyby

After whizzing past Pluto in July 2015, NASA’s New Horizons space probe has been taking deep-space naps by going into hibernation and minimizing the use of essential instruments. The move, aimed at preventing wear and tear, last time occurred in December 2017, but now mission controllers have stated that the probe has woken up and is cruising through the Kuiper Belt, more than 3.7 billion miles (6 billion km) away from Earth, to fly by its next target – an icy space rock named Ultima Thule.

On June 5, mission operators at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory received radio signals confirming that the spacecraft successfully executed the commands provided to leave the autopilot-backed hibernation mode. All the systems came back online as the team expected, indicating the whole thing is working normally and is in good condition.

With that, the New Horizons team has started a series of experiments aimed at prepping the spacecraft for the rendezvous with Ultima Thule at the edge of the solar system, or approximately a billion miles further away (1.6 billion km) from Pluto.

As part of the pre-flyby preparations, the New Horizons team will collect navigation tracking data via NASA’s deep space network. Then, over next two months, they’ll send a series of commands aimed at performing housekeeping work on the spacecraft such as issuing memory updates, checking subsystems and science instruments of the probe and retrieving the scientific data it captured during or before going into hibernation.

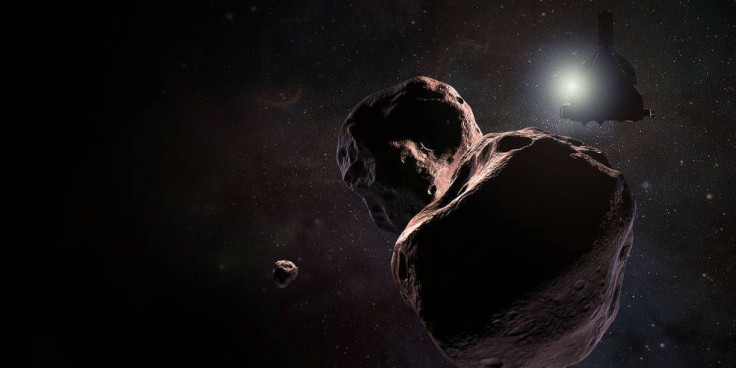

Once all of that is done, the probe will be commanded to initiate a series of observations and take images of Ultima Thule, which would provide a first good look at the icy space object and allow scientists to correct the course of the spacecraft to fly by it. The probe is currently 162 million miles (262 million km) away from the target and covering 760,200 miles (1,223,420 km) every day. According to the team, at this pace, it should reach there by the end of this year and perform the flyby, touted as the farthest planetary encounter in history, scheduled for New Year’s Day 2019.

"Our team is already deep into planning and simulations of our upcoming flyby of Ultima Thule and excited that New Horizons is now back in an active state to ready the bird for flyby operations, which will begin in late August," mission’s Principal Investigator Alan Stern said in a statement.

That said, it is also worth noting that New Horizons won’t be going into hibernation anytime soon again. The space probe will take observations from the flyby and until all of that data, including other science observations from the Kuiper belt, is successfully transmitted (expected to take more than a year), it will remain active.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.