Natural Disasters Are Hitting Harder, And Not Because Of Global Warming

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be in the middle of a massive typhoon, the first thing you should know is that it depends entirely on where you’re standing.

“It can be terrifying, really,” said James Reynolds, a storm chaser based in Hong Kong. He was on the Japanese island of Okinawa on the morning of Sept. 16, 2012, just as Typhoon Sanba rolled in with maximum sustained winds of about 103 miles per hour and gusts reaching 127.

“We’re talking about the wind screaming so loudly that if you were trying to shout at someone 10 meters away, they wouldn’t be able to hear you," he said. "Rain so blinding you wouldn’t even be able to see across the street. Waves crashing so large they inundated my location. When you’re exposed to these elements you’re deafened, you’re blinded, water is getting everywhere and it’s a very unpleasant experience if you’re not prepared for it.”

But Okinawa was prepared for it. There was only one Japanese fatality reported during that typhoon: The victim had gone for a swim at sea. Neighborhoods temporarily lost power and there was some flooding, but no major displacement. Only hours after the worst of the storm had passed, Reynolds was able to get in his car, drive down the highway and use the Internet at his hotel.

“I came through that whole experience unscathed, due to the fact that I was in Japan," Reynolds said. "I was in a sturdy building. If I had been in the Philippines, I’d have been in big trouble.”

Less than three months later, Typhoon Bopha hit the Philippine island of Mindanao with sustained winds of 108 miles per hour and gusts up to 133 -- not much stronger than Sanba was at landfall. But this storm displaced 1.2 million families and killed at least 1,146 men, women and children.

In these two scenarios, it wasn’t the weather that made the difference -- it was infrastructural vulnerability.

This preventable problem boils down to a single paradox: Some of the world’s fastest-growing economies are finding themselves increasingly at risk, precisely because urban zones -- with their high concentrations of people and economic assets -- are swelling too quickly for safety regulations to keep up.

“Many cities, especially in developing countries, are very quickly expanding, and often expanding in hazard-prone areas,” explained Francis Ghesquiere, manager for the World Bank's Disaster Risk Management Practice Group.

He noted that climate change has certainly led to an increase in adverse weather events. But the main reason economic costs of natural disasters have tripled over the last three decades? “First and foremost, the growth of population and assets.”

Stormy Weather

Weather events of similar scale can have wildly divergent impacts from one country to the next -- it’s all a question of relative damage.

Two massive disasters serve as case in point: According to World Bank data, the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011 resulted in losses of US$210 billion. The year before that, an earthquake in Haiti incurred losses of only about $7.8 billion.

But while Japan’s disaster cost more in absolute economic terms, the Haitian tragedy was far more devastating in the long run -- its $7.8 billion in damage amounted to 120 percent of GDP. Japan’s earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown combined cost only 4 percent of GDP.

The relatively high toll of natural disasters, combined with poor societies’ inability to recover from them, puts developing countries at a distinct disadvantage.

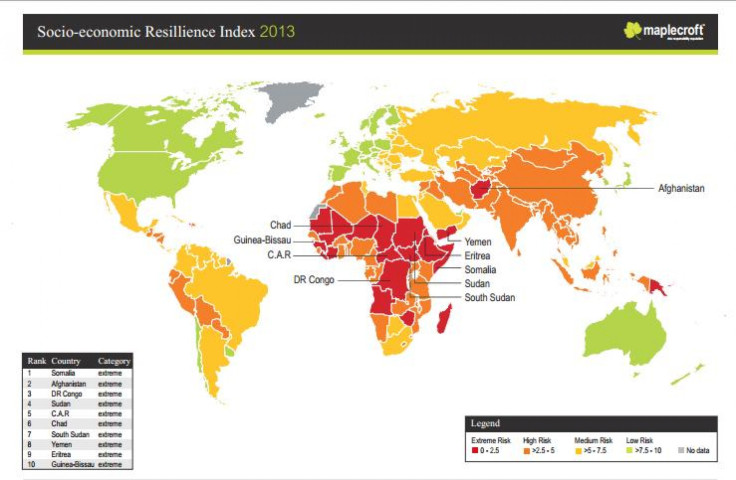

A Natural Hazards Risk Atlas compiled this year by the London-based risk analysis firm Maplecroft ranks countries according to their exposure to risk, their economic liabilities and their resiliency.

Some of the data is unsurprising. The most resilient countries are those that enjoy high incomes and well-developed infrastructure: Japan, Australia, the United States, Norway. The countries that score poorly are one that have been plagued by scourges like conflict, poverty and corruption: Somalia, Afghanistan, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, among others. A single disaster in places like these can undermine years of progress by destroying infrastructure and siphoning off scarce resources in order to fund recovery efforts.

What’s more surprising is that fast-growing economies -- places such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and the Philippines (GDP growth for each topped 4.8 percent) -- are actually the most at risk in terms of relative economic exposure, which is the value of economic assets that might be destroyed or compromised by a natural disaster, as a portion of GDP.

When Maplecroft ranked 195 countries in terms of relative economic exposure, the Philippines was listed as the most vulnerable country on earth. Bangladesh came in second and Vietnam was 12th.

The trend looks likely to continue as more and more small economies rev up.

“We’ve looked at countries which we believe have the greatest growth potential this year,” said Helen Hodge, the associate director at Maplecroft who led the hazard risk research. “Those countries are accounting for substantial proportions of economic output. But those advances in economic output haven’t yet translated into an improved climate for risk prevention over the years we’ve been investigating this issue.”

As a result, developing nations are often caught off-guard when disaster strikes. International donors can usually be counted on to swoop in with some extra funds as global media outlets turn their cameras on the devastating aftermath and grieving survivors.

But this reactive approach is disruptive, inefficient, and far more costly than it has to be.

Blue Skies

For global organizations that make development their mission, one big question has been emerging in recent years: Why hasn’t disaster risk management been a bigger part of the plan this whole time?

The World Bank got very serious about this problem in 2006 when it established the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, or GFDRR. Its goal is to help countries to lay down frameworks for development that include disaster risk management, which can avoid situations where poor countries go into shock each time a disaster hits.

“GFDRR is probably one of the fastest growing programs in the World Bank,” said Ghesquiere, who runs the organization. “If you look at the number of staff, we may have had 20 to 30 staff focused on disaster risk management three to five years ago; we now have more than 130, and it’s growing. It’s also growing in the number of operations on the ground, with a lot of effort in helping local authorities better understand the risks to which they’re exposed.”

Disaster risk management wonks gathered to discuss these ideas in July of last year in Sendai, Japan. The conference didn’t make headlines, but it was one of the most important events the international development community has ever convened.

“[The Sendai Dialogue] is probably the first time that the topic was really brought to such a level of attention, to more than 150 delegations from ministries of finance, with both the World Bank and the IMF insisting that this is becoming a very serious problem that needs to be addressed in the long-term development planning process, not just in the response system,” Ghesquiere said.

A comprehensive document called the Sendai Report was compiled in advance of the meeting; it outlined some of the key principles that now influence global efforts to keep development on track in emerging economies, come rain or come shine.

“The economic losses from disasters over the past 30 years are estimated at $3.5 trillion. Last year [2011] was the costliest on record, seeing estimated losses of around $380 billion," said the report, which urged a comprehensive approach to keep domestic governments fully engaged in disaster risk management indefinitely. Losing focus will be a constant danger, especially during those times when disasters fall from the headlines.

“Last year was, fortunately, one of the least deadly years on recent record for natural disasters -- that’s obviously great news,” said Maplecroft’s Helen Hodge.

“Part of the reason that occurred was because most of the major events we saw in 2012 were in developed countries. However, that does bring the risk of complacency. Once disasters fall out of people’s minds and out of decision makers’ agendas, the issue risks being sidelined.”

As a severe weather reporter, Reynolds has seen that phenomenon firsthand.

“The main focus is always on Atlantic hurricanes; it always has been,” he said. “And still to this day, when big storms pass through that region, that’s where the main media focuses. I’ve been trying to report from the areas that have been traditionally underreported – to go there and be a one-man-band, so to speak.”

But disasters in developing countries may be harder to ignore as they become more frequent, as they are likely to do as a result of climate change.

A November World Bank report notes that since pre-industrial times, average global temperatures have risen 0.8 degrees Celsius and sea levels have increased by 20 centimeters. Another 4 degrees of warming by the end of the century -- a likely scenario, according to a growing consensus of scientists -- will result in more intense storms, deadly droughts and famines, major floods and widespread disruptions of ecosystems.

But before climate change wreaks more havoc, development professionals hope to see the administrators of emerging economies set up programs that will help them face those risks head on.

Somewhere Over the Rainbow

International donor and media responses to disasters are still necessary to help fund recoveries, but history has shown that the follow-through can falter as attention spans run short. Calamities like Typhoon Bopha and the Haitian earthquake, for instance, are still ruining lives long after the news cycle has moved on.

In Haiti, more than 222,000 people died since the Jan. 2010 quake. Billions of aid dollars have been dispersed, but more than 300,000 people remain homeless. The food situation is insecure, and most people live in poverty.

In the Philippines, hundreds of people are still missing months after Bopha hit. Hundreds of thousands are displaced and living in tents and shelters. Tens of thousands are eat risk of malnutrition.

Ghesquiere notes that the World Bank is working with Philippines to establish stronger institutions that can respond more proactively to adverse weather events.

“Manila is highly susceptible to flooding, and so we’ve worked with the local authorities to design a large investment program to reduce this risk of floods, which is now finalized -- an investment program over probably the next 10 to 20 years that is estimated at about $8 billion of investments,” he said.

“Countries tend to, unfortunately, learn from disaster. The Philippines has had its fair share of adverse natural events in recent years, and you can see the system certainly coming together and the response system improving.”

If all goes well, this could be the beginning of a success story – like Japan, which has worked for decades to minimize risks. The earthquake and tsunami disaster was a tragic one that killed more than 20,000 people, but it is worth noting that early warning systems were in place, hundreds of thousands of people were evacuated in time and troops were on the ground within hours of the incident.

“I think we don’t give enough credit to the Japanese authorities,” Ghesquiere said.

“You have to realize that reaching this level of business standards is not done overnight. It has taken 150 years for Japan to change its building [methods] and to have an infrastructure that can sustain this kind of tremor.”

If the same kinds of institutional changes can be implemented around the world, perhaps rainy countries could gain the right tools to avert flood damage, drought-prone regions could avoid exacerbated famine, and communities near fault lines could build structures to withstand major quakes.

Hodge notes that this is a long-term goal – progress would come in stages.

“Being able to forecast storms is one of those steps toward building resilience that can be done on a swifter timescale, whereas improving infrastructure, improving building codes and enforcing them takes a little more time.”

In an ideal world, these sorts of measures would work side-by-side with industrialized countries’ efforts to cut down on their outsized contribution to the warming of our shared atmosphere. It’d be a win-win for everybody – the antidote to years of tragic losses.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.