New Investor Protection Rules Expose An Industry War For Americans’ Retirement Assets

The biggest regulatory battle to face the financial industry since the Dodd-Frank Act passed a milestone Wednesday as the Department of Labor released a final rule addressing the conflicts of interest endemic to the retirement advice industry.

The new guidelines, which require financial advisers to disclose conflicts, and compel them to act in the best interests of their clients, didn’t come without a fight. Lobbyists for Wall Street broker-dealers and insurance companies spent millions of dollars in an attempt to convince the Labor Department — and Congress — to alter or delay the rules.

But the reforms have been greeted with open arms by registered investment advisers, fee-only planners and other players in the retirement industry who are currently held to a fiduciary standard — a requirement that advisers put clients’ interests first.

These businesses are optimistic that the new rules will push more clients from traditional brokers to other models, from fee-only planners who charge a flat rate on assets overseen to robo-advisers that use algorithms to cheaply invest clients’ savings.

“There’s going to be a spotlight put on fees that’s going to drive demand for low-fee products,” John Blood, chief executive of Efficient Advisors, said. Blood, whose company operates under a fiduciary standard with clients, hopes the new regulatory regime pushes investors from establishment broker-dealers to a new crop of tech-savvy fiduciaries like himself.

It could be also be good news for robo-advisers like Betterment and Wealthfront, which have cornered an increasing share of the asset management market as investors reject the kinds of fees charged by traditional brokerages. This class of adviser has seen assets grow from virtually zero in 2012 to a projected $300 billion by the end of the year.

The Labor Department rule aims to protect the retirement savers who roll some $300 billion in assets from 401(k)s into individual retirement accounts, or IRAs, every year. The Obama administration has held that advisers overseeing these rollovers earn billions of dollars in extraneous fees and commissions every year, eroding the returns of retirement savers.

The new rule largely preserves previous incarnations of the guidelines, requiring steep disclosures of conflicts of interest and making advisers sign a legally enforceable contract with clients promising to work in their best interests. Investor advocates like Americans for Financial Reform and the Consumer Federation of America, which lobbied extensively for the reforms, celebrated Wednesday’s announcement.

The release did contain some concessions on matters that industry groups had argued were unworkable. Advisers will still be able to sell proprietary products and variable annuities, and they will have more leeway in approaching and advertising to clients without signing a fiduciary pledge. Paperwork requirements were diminished.

But despite the compromises, industry analysts expect that the new guidelines, which take full effect January 2018, will deeply affect companies like Wells Fargo and LPL Financial — firms that have faced the dual threats of regulatory pressures and competition from low-cost digital advisers.

“The full-service investment advisory industry is undergoing a historic shift, driven by an actively engaged investor population,” a forthcoming J.D. Power study asserts. “Fewer and fewer investors are putting blind faith in their advisers’ investment recommendations.”

In essence, the increased scrutiny of investors and regulators has threatened the basic business model of broker-dealers who sell mutual funds and other products. A study by Morningstar found that the Labor Department’s restrictions on fees and commissions alone could cost the industry a combined $19 billion.

On Tuesday, International Business Times reported on the changes looming for Edward Jones, whose business model still rests largely on commissions on the sale of products like variable annuities and mutual funds, whose third-party providers pay handsomely for Edward Jones to promote the products.

Edward Jones has argued, along with many in the industry, that the new rule could constrain their ability to serve less affluent clients, particularly those with less than $50,000 in the bank. They point to studies of similar measures introduced in the U.K., where new regulations caused “advice gaps,” according to consulting firm Oliver Wyman, purportedly affecting advisers’ “ability to profitably serve smaller investors.”

“The brokerage community needs to make certain fixed-dollar amounts to be profitable for a smaller account,” Mitch Tuchman, managing director of Rebalance IRA, said. “The smaller the account, the more then need to find commissions and loads to break even.”

As one former annuity salesman wrote to the Labor Department, “I worked with many types of clients, most of whom were middle-class individuals, and 100 percent of my compensation was in the form of commissions.”

The new rules do not bar commissions but require brokers to provide additional disclosures and promise that their advice is truly in the best interest of clients. The fiduciaries with whom IBT spoke expected the new mandates to raise investors’ awareness of the fees and conflicts that the president’s Council of Economic Advisers has said drive $17 billion a year from the accounts of retirement savers to Wall Street. Industry groups dispute those numbers.

Currently, most investors have little idea whether their adviser is a fiduciary or even what fees they charge. As many as 60 percent of investors don’t completely understand the extent of their fees, according to the J.D. Power study.

“Although many investors don’t understand the meaning of ‘fiduciary duty,’” a 2012 Securities and Exchange Commission report found, “investors generally treat their relationships with both broker-dealers and investment advisers as relationships of trust and expect that the recommendations they receive will be in their best interests.”

Until now, that has been a mistaken assumption. “Consumers and clients really don’t understand this,” Blood said. “They hate the fact that a fiduciary standard is even necessary. They feel like it should be the expectation that a financial adviser is acting in their best interest at all times.”

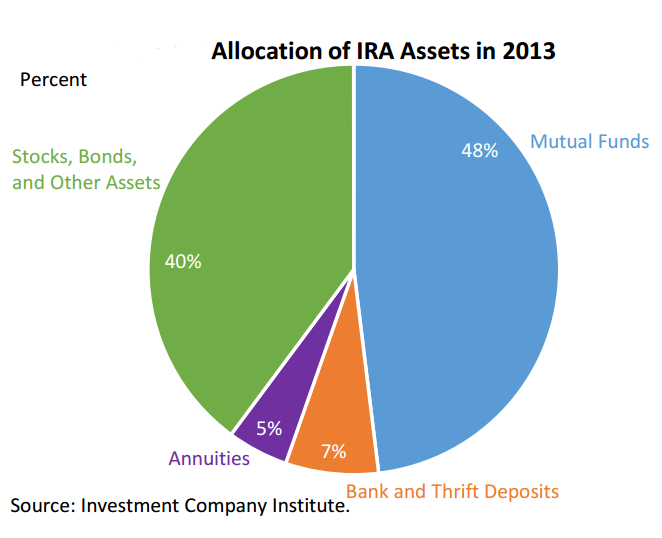

While advisers who oversee pensions and 401(k)s must abide by a fiduciary standard, brokers who deal with IRAs aren't required to act solely on their clients' behalf. As retirement assets have slowly shifted to IRAs in the past several decades, this inconsistency has grown more apparent.

Though industry groups support a type of best-interest standard, they have greeted the Labor Department’s new rule cautiously. “We continue to believe the department's methodology is greatly flawed and lacking sufficient empirical basis,” the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, an industry lobbying group, said Wednesday. Like other groups, Sifma said it was still reserving final judgment as it examined the new rule at length.

The Chamber of Commerce has threatened to sue the government over the rule, and Jaret Seiberg, a policy analyst with Guggenheim Securities, doubted that stance would change. “Litigation stills seems inevitable,” he said in a note to clients Wednesday.

Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America, who has applauded the new regulations, doubted the industry would back down. “They will soon have a list of reasons why they can’t possibly comply with those rules,” she said. “Their desire was to maintain the loopholes that allow them to act as advisers without being regulated as advisers.” Those loopholes have been narrowed by the rules.

Tuchman, whose firm Rebalance IRA uses a mix of index fund strategies and in-person advising to provide low-fee investment services, welcomed the fight. To him, the changing regulatory landscape represents healthy industry disruption at work. “It’s what happens in capitalism.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.