New Seafloor Map Reveals Thousands Of Uncharted ‘Seamounts,’ Other Mysteries Of The Deep Ocean [PHOTOS]

When it came to drawing maps of the ocean floor, scientists were stuck with crayons when the task required Photoshop. Now, improvements in satellite radar have brought every nook and cranny of Earth’s seafloor to life with twice the precision of previous models, according to a new study published Friday in the journal Science.

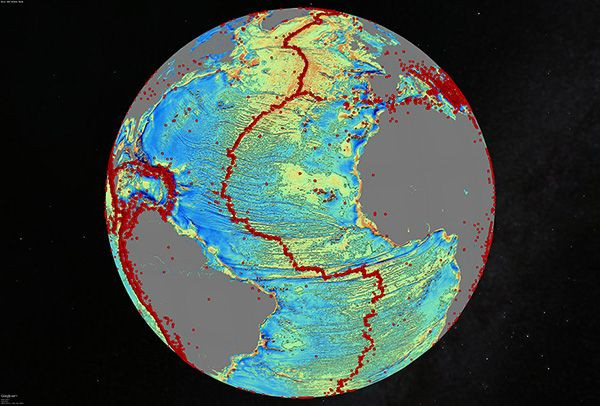

The new satellite data offers a window into Earth’s geological past and has uncovered thousands of previously uncharted seamounts, hidden ridges and unknown tectonic plates. The images, stitched together by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, have implications not only for fisheries and conservation groups, but also for understanding how oceans transfer heat and influence climate, according to researchers.

“We know much more about the topography of Mars than we know about Earth’s seafloor,” Dietmar Muller, a geophysicist from the University of Sydney and one of the project’s researchers, told the Guardian. He said the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 underscored just how little scientists know about what’s at the bottom of the ocean. Roughly 80 percent to 90 percent of the planet’s seafloor is uncharted, in part because using ships equipped with sophisticated acoustics to map it would cost between $2 billion and $3 billion and would take years to complete, the Guardian noted.

Researchers used a technique for mapping seafloor topography known as the gravity model, which employs satellites fitted with radar to take detailed images of the contours of Earth’s ocean floor. It's based on the fact that water follows gravity and is pulled into highs above tall seamounts and dips into depressions over deep trenches. Previous maps of the seafloor have relied on this method, but advances in the technology have greatly improved its accuracy, according to BBC News . Many of the ocean floor’s features only became visible with new gravity data because they remain covered by deep sediments.

“The team has developed and proved a powerful new tool for high-resolution exploration of regional seafloor structure and geophysical processes,” Don Rice of the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences, which partly funded the research, said in a statement. “This capability will allow us to revisit unsolved questions and to pinpoint where to focus future exploratory work.”

The newly identified seamounts measured at least 1.5 kilometers, or nearly one mile, tall. Previous models only detected seamounts taller than 2 kilometers. “The kinds of things you can see very clearly now are abyssal hills, which are the most common land form on the planet,” David Sandwell, lead author of the study, said.

Among other things, the new data showed a mid-ocean ridge in the Gulf of Mexico and a massive scar in the South Atlantic Ocean formed by an ancient hotspot that cracked the Earth's crust wide open. The maps could help geologists pinpoint new natural gas reserves and other resources.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.