This New Tech Is Making Prison Inmates Flush Their Smuggled Cell Phones Down Toilets

They come in through the mail, tucked in babies’ diapers on family visits and sneaked in by prison guards. Police say inmates use cell phones to plan gang attacks or coordinate hits on the outside, and prison officials are desperate to keep them out. California, for instance, has spent considerable resources to remove more than 30,000 phones from inmates since 2012.

Still, thousands of phones are still out there. New technology may help change that.

A new device to block or monitor cell phone use in prisons will be on display at the National Sheriffs' Association's annual conference, which kicks off today in Baltimore. The event is a sort of Consumer Electronics Show, but for police and prison officials.

Cell phone-monitoring technology might be legal for prison and jail officials. And it might certainly make the environment safer on the inside. But it's worth considering the implications of what could happen if this technology is used elsewhere in law enforcement or intelligence gathering. There is little stopping the tech being used in prisons today to be used on those merely suspected of having committed a crime.

At this conference, however, the scope of this technology will be more limited.

"The problem with cell phones permeates every correctional facility,” says Debra Kurtz, a marketing manager for Metrasens, maker of the Cellsense. The Cellsense is 7-foot wand-like device that uses ferromagnetic detection to root out cell phones on an inmate’s body or in a cell. Kurtz says that the wand is more effective than a traditional metal detector or hand-held wand, and that it can detect a cell phone or small razor blades hidden inside an inmate’s body.

Yes, anywhere in their body.

Cellsense is one of the few devices endorsed by the National Sheriffs' Association. Kurtz says it is currently used in correctional facilities in every state, but would not comment on exact figures.

Whole Networks Monitored

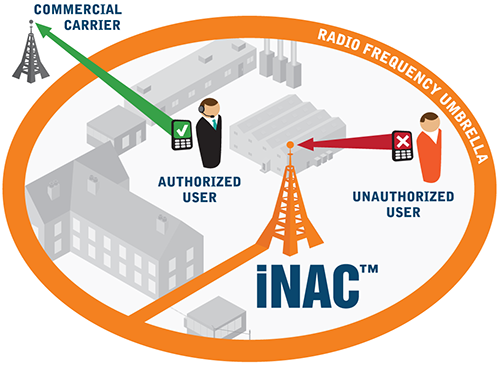

Other providers take a more comprehensive approach. Maryland-based Tecore Networks has provided a patented “Managed Access System” to prisons and jails around the country since 2010. The system takes over the jail’s entire cell phone network to selectively permit or deny specific numbers from being transmitted through the airspace.

A company representative, Markie Britton, explains that Tecore leases local airwaves from companies like Sprint and Verizon. When an inmate tries to place a call or send a text from within the jail walls, the communication is blocked, and a recording plays informing the inmate that they are breaking the law.

Tecore Networks has contracts with three jails -- two in Baltimore and one in Mississippi. Britton says thousands of calls have been intercepted.

In fact, she says, the system is so successful that the jails have begun experiencing a new problem altogether: plumbing issues. Because the system renders the cell phones useless, many inmates, she says, try to flush them down the toilet.

'You Are Making An Unauthorized Call'

The technology is not perfect. Last February, the Baltimore Sun reported that people walking near the Baltimore City Detention Center had their calls interrupted by Tecore’s system. "I got this recording," one person told the Sun. "It was a man's voice and it said, 'You're attempting to make an unauthorized call.’ ”

And not every type of cell phone detection is legal even within prison walls. The Federal Communications Commission, which will be represented at this week’s trade show, says cell phone jamming technologies, which are widely available, are not to be used in prisons and jails. “Cell phone jamming doesn’t just block inmate calls -- it can also interfere with mobile 9-1-1 calls and public safety communication,” the FCC noted in a recent ruling.

Harris Corp., which markets the Stingray cell phone monitoring device, will be on hand at the conference. It’s unclear if the company will be marketing the use of Stingrays for jails and prisons. A company representative did not return our request for comment.

Many critics of the Stingray say it is used by police to intercept messages from citizens who have done nothing wrong. The law is murky on whether these types of technology can be used on prisoners.

Brian Owsley, a former magistrate judge in the Southern District of Texas, denied a request in 2012 from prosecutors who wanted his permission to deploy a Stingray to find a smartphone hidden behind bars.

He said many judges simply don’t understand Stingray technology, and consequently authorize the use of a Stingray when prosecutors only asked to use a pen register, a device that records telephone numbers from a phone, a far less invasive method of surveillance.

“I think if you had five judges and asked them questions about if this is legal, you would probably get 10 different opinions,” Owsley, now an assistant professor of law at the University of North Texas Dallas College of Law, said by phone.

“Prisoners' rights are curtailed in a way that yours and mine are not, but I think there is a need for a search warrant because how much data is being taken. It’s protecting all the people around there, Stingrays affect all the guards and all the people.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.