New York City Considering Landmark Protections For Freelancers Who Suffer From Wage Theft

If employees get stiffed on a payment from the boss, they have a clear path for recouping lost pay: Workers can file a complaint with state or federal labor authorities. Then the government can go to court to win back pay, swallowing the legal fees.

Freelancers, on the other hand, have no such protections. Now a first-of-its-kind bill in New York City aims to plug that gap — and on Monday it saw its first hearing.

“All workers deserve to get paid on time and in full for the work they do,” said the legislation’s leading sponsor, Councilman Brad Lander of Brooklyn. “Traditional W2 employees at least have some protections from wage theft, but freelancers and independent workers don’t. [We asked] what can New York City do to provide them? And here we are.”

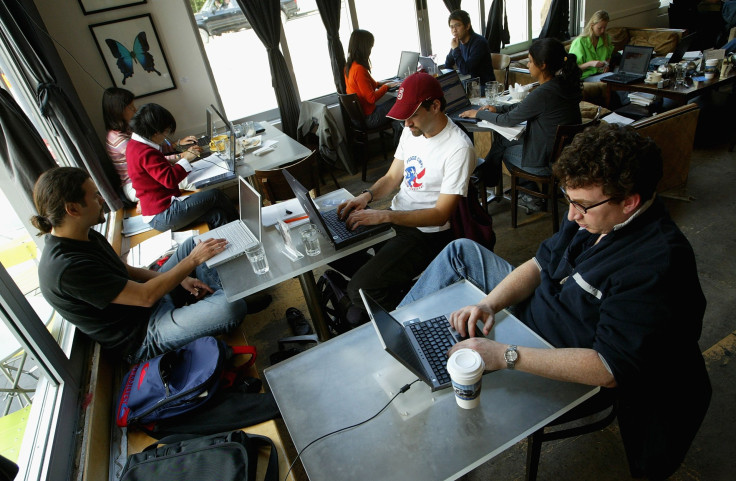

Lander introduced his bill last December after hearing from freelancer advocates like the New York City-based Freelancers Union. The group is not a traditional labor union — it does not charge any dues to members and it does not bargain with companies — but serves as a broad network and advocacy organization for freelancers. Last December, it released a study documenting the extent of wage theft for this slice of the workforce, from espresso-swilling writers and graphic designers to accountants and adjunct professors.

One in every two freelancers had trouble getting paid in 2014, according to the report, which polled more than 5,000 such workers across the country. Usually the difficulties boiled down to late payment—a problem that affected 81 percent of those who said they had payment troubles. But roughly a third of that group said they performed work for which they did not get paid at all. The average amount of income lost in 2014 was $6,000.

“For freelancers, this is one of the most important issues,” said Sara Horowitz, founder and executive director of the Freelancers Union. “We tell people to build an American dream, we tell them to be entrepreneurial, and then the group that’s doing that, we make sure to clip their wings without any security.”

Debates persist about how large a share of the U.S. workforce is actually made up of freelancers. The Freelancers Union estimates that 54 million Americans are now doing some type of freelance work. Federal data is more elusive: Surveys do not specifically keep track of freelancers, although about 15 million workers today identify as “self-employed,” according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That figure, critics say, fails to capture a full picture of the labor force such as those who do contract work in addition to a traditional job.

However many freelancers exist, research suggests their ranks are likely growing to a modest degree. And their lack of workplace protections are emphatically not up for debate. Advocates have increasingly called for new regulations to tackle the problem, from authorizing groups of independent contractors to form unions to extending minimum wage protections.

Under the current proposal, New York City-based freelancers who are not paid on time would have rights to pursue back pay that are comparable to those of traditional employees. First, the bill would require anyone who hires an independent contractor for $200 or more to create a written contract specifying the kind of work to be done and the payment date. It would then require workers to be compensated within 30 days of the specified payment date, or of the contractor completing the service, whichever comes first.

Freelancers who get stiffed on compensation would be authorized to file complaints with New York City’s newly created Office of Labor Standards, the agency in charge of enforcing the city’s new paid-sick-leave mandate. Under the proposal, the city agency would then be empowered to investigate complaints, mediate disputes and impose penalties on lawbreakers such as so-called double damages and attorneys' fees. Individuals would also be free to pursue claims on their own.

Under current law, freelancers can pursue claims against contractors for breaching contracts on their own. But the high costs and length of time lawsuits take often discourage freelancers from taking this route, critics say.

Horowitz said the bill is especially important for cities like New York that rely on work from creative professionals. She referenced the work of Richard Florida, an urban studies theorist who has written extensively about the rise of the “creative class.”

“If New York City wants to keep the people who work here, who are creative and work day in and day out, the number one thing for workers is getting paid,” she said. “We’re just putting in the very basic safeguards. I’m not persuaded this is going to cause any major disruption.”

At the hearing Monday, representatives from New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration indicated broad support for the bill’s intentions. But they also raised concerns about the city's ability to enforce the proposal as written, such as making judgments about contract disputes.

In an interview before the hearing Monday, Councilman Lander said he was open to making changes and amendments in order to pass the bill.

“This is the first time a municipality has tried to do something like this, so we’re eager for people to help us think through the implications and get it right,” Lander said. “We want to make this as straightforward and simple as possible for both employers and freelancers, but obviously we’ve got to fix the problem.”

If the city’s commerce committee votes to advance the bill, it would move to the full City Council. The current version of legislation counts the support of 28 councilmembers. It also has the backing of progressive organizations like the National Employment Law Project and Local 32BJ of the Service Employees International Union.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.