Nigeria's 'King Of Guns' Fights Boko Haram With Ancient Weapons, Cell Phones -- And A Little Magic

YOLA, Nigeria -- Abubakar Nyako says he shot his first gazelle when he was just 10 years old -- and on his first attempt, no less. He says he can use any weapon accurately, as long as he can watch someone else fire it just once.

Though he first learned to shoot on makeshift, locally manufactured rifles, these days he prefers a double-barreled shotgun -- and produces a cartridge from his long, white robe to illustrate the point. Now, at 51, he’s more commonly referred to by the name that better reflects his status as head of vigilante groups in Adamawa state: Kiki Bindinga, King of Guns.

Slow and considered, Nyako takes time to answer most questions, except for one. When asked about the greatest security challenge that he’s facing, he answers immediately: Boko Haram.

For the past two years, he’s controlled a network of men who regularly take up arms to fight off attacks from the militant group that has been terrorizing the northeast of Nigeria since 2009. Each militia is composed of locals who work other, more ordinary jobs -- many in farming -- but manage to coordinate and use what weapons they have to stave off attacks on their villages or those nearby.

The men are filling the gaps left by Nigeria’s army and police, which have been largely inefficient in the fight against Boko Haram. Though they lack the funding of the Nigerian military, these “vigilantes” or "hunters" often work with their official counterparts to provide the necessary know-how and local knowledge needed to repel Boko Haram or take back territory.

These groups aren’t a recent invention to stop the Islamist insurgents. Local vigilante groups have existed for generations, with leadership models already in place, Nyako says. He himself took over as leader from his father, who took over from his father, and so on. And an endorsement from the local Lamido, meaning leader in the Fula language, doesn’t hurt either.

Each town has a head, who reports to a regional head, who reports to Nyako. Whenever there’s any threat, he’s the first to get a call, he explains, nodding to his cell phone sitting close at hand.

When Boko Haram members attacked the city of Mubi, Nyako’s vigilantes were the first on the scene, “with military coming behind,” he says with a laugh. This is a typical occurrence. Local media sources are starting to credit these groups for the Nigerian military’s recent victories in the northeast.

“The military like us,” says Kwaya Zakka, a hunter who currently heads a special team of local vigilantes at the American University of Nigeria. “They have come to understand our importance.”

As in many parts of Nigeria, nobody trusts the police or military to perform their jobs, which has left local militias to fill the gaps -- mainly with their own money.

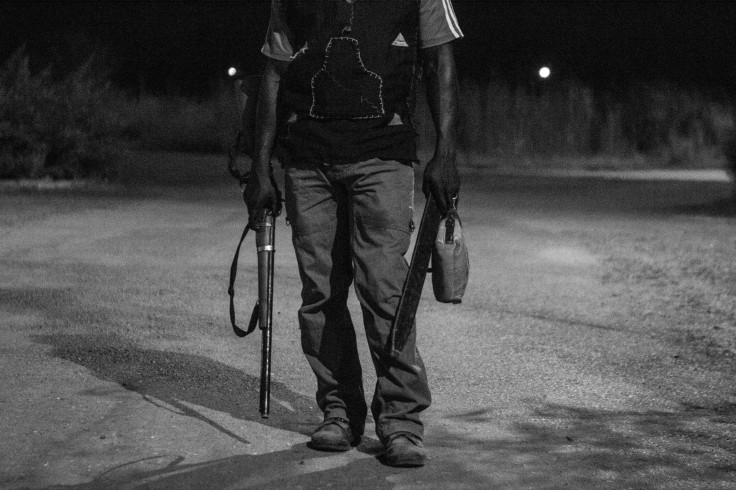

“The police, the army, they don’t do anything. All we can do is help ourselves,” Zakka says, stopping to lean on his rifle during a seven-hour patrol shift outside the university. The school has contracted him to organize a group of locals to patrol the area around the property after dark.

“Security does not come from sitting around inside,” he says, picking up his walking pace. “That’s why we’re out here in the bush -- I like it better.”

Unlike the military and police, militiamen have no direct public funding, so they’re on their own for equipment. Consequently, the vast majority of weapons are made locally, sometimes by hand. The long guns most of them carry are made mostly of wood, with iron barrel and one-shot capacity. Others tote long sticks tipped with a metal point, machetes or long wooden clubs.

The lack of funding also means that most of them are doing this part-time, usually in two-week shifts, according to Zakka. “If you just stay there the government won’t pay you,” he says. “If your crops spoil on the farms, what will you do for your next meal?”

But honing their skills, they say, doesn’t require a great deal of money. Nor do they need sophisticated weapons. Most vigilantes begin working in the rougher parts of the bush when they are still children, and feel better equipped than anyone to spot trouble from a distance, even in the dark. They can handle their makeshift weapons more skillfully than soldiers, or Boko Haram, can handle their modern Kalashnikovs.

And according to the King himself, these vigilantes, also called hunters, have yet another advantage. “Sometimes, even if you stay with me, you won’t see me,” he says. “But I’m still here. I can even touch your arm and you won’t see me.”

Does he mean magic? To clarify, he looks to a translator who tries to explain that Nyako has traditional beliefs that protect him in the field. But soon, he stops and shakes his head.

“Ah, you 'batures' most of the time don’t believe in it,” the translator says, using the Hausa word for foreigners. “Just know that if things go wrong, you cannot harm him, you cannot harm his followers. This is how we win.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.