Nigeria's Troubled Exit Path For Repentant Jihadists

Gaunt men sit in the shade sewing hats while women in headscarves cook leaves, watching children play as the dry wind blows through the thatched huts.

It's a typical scene in the sprawling camps set up for over two million people who have fled jihadists waging war in northeast Nigeria -- and where Aliyu, Abubakar, Muhammad and Mallam now also live.

But the desolate site is a far cry from where these four men had expected to end up after completing a government programme to deradicalise and rehabilitate Boko Haram fighters.

The years since entering the custody of the authorities -- time mostly spent in overcrowded and filthy cells -- have been traumatic, the men say.

Now left to live in dusty camps with no jobs in sight, they say the government has not delivered the fresh start promised.

The deradicalisation programme has also targeted the wrong people, with participants saying that many civilians, rather than fighters, end up in the hands of the military.

Over more than a decade, Boko Haram jihadists, along with combatants from dissident offshoot the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), have killed at least 40,000 people.

In response, Nigeria has launched military offensives and introduced Operation Safe Corridor in 2016 -- a programme that would offer an exit route to militants willing to lay down their arms and embrace peace.

Fighters officially are first screened and those deemed low risk are transferred to a centre in Mallam Sidi, a town in northeastern Gombe state.

For six months, they are supposed to undergo vocational training, religious and basic education and receive psychosocial counselling.

The United States, European Union and Britain have given millions of dollars to help the programme, which is supported by the UN's International Organization for Migration (IOM) among others.

Nigeria's armed forces coordinate the scheme, according to official documentation, with support from 17 groups including government departments, UN agencies and NGOs.

"Operation Safe Corridor has recorded tremendous successes," its head, Brigadier General Mohammed Maina, said early last month in written responses to AFP's questions.

"Over 800 repentant ex-combatants have been successfully deradicalised, rehabilitated and reintegrated."

Many more could soon be eligible. The army said earlier this month that 335 fighters who recently surrendered were "undergoing comprehensive security profiling."

Yet the four men who participated in Operation Safe Corridor and were interviewed by AFP earlier this year gave a stark account of their experiences.

Once in custody, they were held without charge in brutal conditions for several years before even reaching the rehabilitation scheme, they said.

And two of them, Abubakar and Mallam, said they were farmers -- not former insurgents -- who were wrongly detained along with many other civilians, including children.

The individual stories of the four men could not be independently verified.

But several reports including by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), International Crisis Group and Amnesty International have extensively detailed similar claims based on hundreds of interviews with others who have completed the programme and officials.

In a report this year, Crisis Group said it had spoken to 23 people who had been through the scheme.

"At most" a quarter of those at the rehabilitation centre with them were "low-level but committed jihadist recruits," it said.

"Most of the others... are civilians who fled areas controlled by Boko Haram and whom authorities then mistakenly categorised as jihadists and detained before sending them into Safe Corridor," the report said.

Maina denied that civilians were being sucked into the programme, saying: "Ex-combatants are chosen after thorough profiling and investigation."

Complicating matters further, a source with extensive knowledge of the programme who spoke on condition of anonymity said that several dozen disengaged senior insurgents, including commanders, had also passed through the deradicalisation centre, under a different scheme.

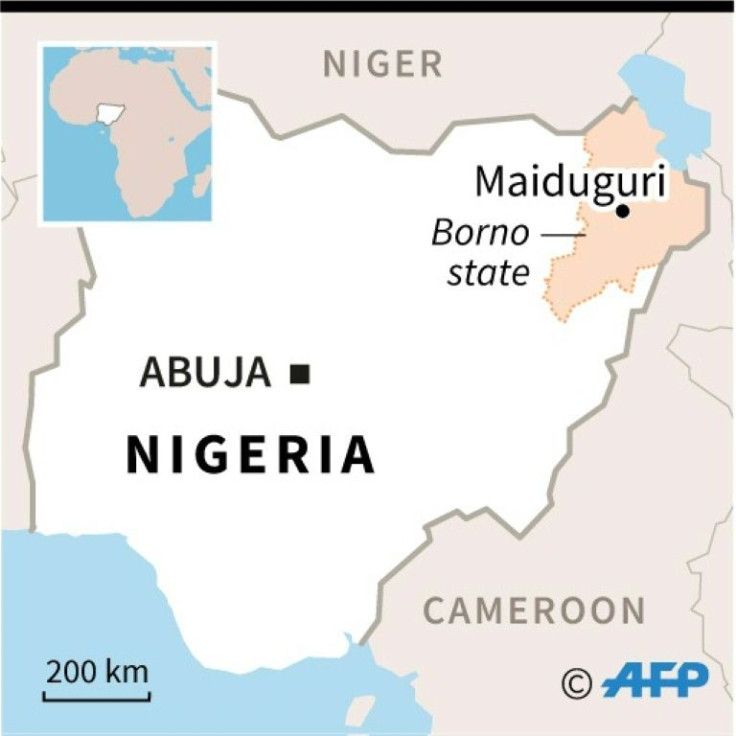

Abubakar, 48, said he earned a decent living as a farmer until Boko Haram fighters took control of his village in northeastern Borno state.

AFP is not identifying specific locations or dates in this story to protect the participants' identity. All four of their names have also been changed.

But, Abubakar said, when the Islamist extremists arrived, everything changed.

"My income started reducing because they would take our crops... even the food we prepared," said the father of three.

"They were watching, monitoring us... we were trapped. There was no other way, they had guns."

Mallam, 52, farmed peas, guinea corn and beans in a different village in Borno.

When Boko Haram arrived there too, the men were told to grow beards and women forced to stay indoors.

He said he once received 80 lashes because he bought cigarettes.

Both farmers decided to escape with their families.

"We left in the middle of the night... There were about 100 of us," said Abubakar, who had heard on the radio that the government was urging civilians to leave Boko Haram-occupied areas.

Despite fearing capture by the insurgents, they felt they had little choice.

"We knew that one day they (Boko Haram) would kill us because we didn't accept them," Mallam, who has five children, said.

But once the two farmers reached military-controlled areas, they were detained by security forces, they said.

Suspected of supporting the jihadists, they were taken to Giwa barracks, a notorious military detention site in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state.

It would be just the first stage of their time in custody.

Abubakar and Mallam say they were held at the barracks for eight and four months respectively.

"There was no food, no toilet, parasites everywhere... people were dying on a daily basis," Mallam said.

Abubakar said that he and his 13-year-old son were in a cell with 450 people.

"We all had to stand because it was so congested," he recalled.

They were divided into two groups and his son was taken away.

It was only when he saw him again nearly six years later that he learnt his son had been released after a few months in Giwa.

Amnesty said in 2016 that the military had transferred alleged Boko Haram members and supporters to military detention sites like Giwa barracks "even if there is no evidence the individual ever committed violence against another person".

Asked about Abubakar and Mallam's claims, army spokesman Onyema Nwachukwu said that although he was unaware of the two men's specific cases, "they must have been involved, willingly or unwillingly".

"We do not detain people arbitrarily," he told AFP in an interview at his office.

Providing food, fuel or medication to Boko Haram, even by force, could make them suspects.

Nwachukwu also said that the army "does not arrest children" but that women recruited by Boko Haram who end up in detention sometimes ask to keep their children with them.

Ex-Boko Haram members Aliyu and Muhammad were also initially taken to Giwa barracks after surrendering -- and have similarly bad memories.

"They told us that we would spend two to three months in Giwa, not more than five months, but it turned into 18 months," Muhammad said.

"It was very horrible."

Aliyu says he was radicalised aged 18 when a neighbour began preaching, giving him money and talking to him about "the corrupt government".

He was persuaded to leave his hometown and travel to Sambisa forest, Boko Haram's main hideout.

After studying the Koran and receiving basic weapons training, Aliyu, now 28, became a gunrunner and later a fighter, taking part in "big attacks".

"We did it because of religion," he said. "It was our duty."

Muhammad, now 25, was a child beggar when he met a preacher who told him about Mohammed Yusuf, Boko Haram's founder.

The man who became his mentor sent him to a religious school in "Fallujah" -- Nigerian jihadists often give places an Iraqi or Afghan name -- and he was eventually sent off for "jihad".

"I was eager to fight," Muhammad, then illiterate, said.

"I understood we were fighting a war against the government. We were taught this was the right path."

Both say they were in Boko Haram for about six years but began to doubt its practices in 2016.

"They would do things without reason... killing, stealing, which is against religious teachings. And I saw them taking drugs, some of them," Muhammad said.

At the time, the Nigerian army was on the offensive, regaining control of territory with neighbouring countries' military support.

When the Boko Haram recruits heard the government was offering vocational training if they surrendered, they decided to make a break for it.

But it would be almost two years before they entered the deradicalisation programme.

Army spokesman Nwachukwu disputed the length of time that Aliyu and Muhammad said they spent in Giwa but stressed the process was "not automatic".

It takes time "to establish the fact they have genuinely abandoned the cause and are willing to become responsible members of society", he said.

International donors, partners and others have criticised the screening process which is also designed to weed out high-risk suspects for eventual prosecution.

It "remains opaque, with no independent oversight, records, nor public specification of the screening criteria", USAID noted in a report this year.

Former combatants Muhammad and Aliyu said they saw many civilians while in detention.

"In my cell of 260, we were 12 real Boko Haram," said Aliyu.

"This is injustice, frankly," said Muhammad.

In his cell of 300 people, he said, "not up to 20 were real Boko Haram".

AFP could not verify the numbers but in response to their claims, programme director Maina said the screening process at Giwa "may be imperfect but it is still very thorough".

In official documents seen by AFP, the Nigerian government acknowledges that some Boko Haram "associates" are victims of the insurgency but says that Safe Corridor offers them "viable alternatives".

So-called associates can include voluntary or coerced recruits, abductees, family members or people held on suspicion of Boko Haram affiliation, one document said.

Amnesty said that even those determined to be innocent were generally not released quickly if they had lived under Boko Haram for a long time.

Next -- in the second phase of their time in detention -- farmers Abubakar and Mallam said they were sent to a maximum security prison in Maiduguri and held without charge for at least three more years.

"I expected the military to keep me safe, but it was the opposite," said Abubakar.

Aliyu, Muhammad, Abubakar and Mallam eventually arrived at their destination -- the rehabilitation centre in Gombe state.

They were taught skills such as carpentry, laundry service and welding and received help from social workers, drug use experts, teachers and spiritual leaders.

"We could sleep, we had mosquito nets, pillows," Abubakar said.

The illiterate were taught to read and write and participants were given materials aimed at countering the narratives drummed into them by the jihadists.

Both former fighters said the programme helped change their views.

"Today if someone wanted to do jihad, I would say 'do your religion at home, but don't go and fight'," Aliyu said.

"They (Boko Haram) betrayed my understanding of jihad to serve their self-interest," Muhammad said.

But for Abubakar and Mallam, the time at the Gombe centre was just another prolonged detention.

"We were sent there to suffer," said Mallam, "but at least we were released."

All four say they were kept in Gombe for about 12 months.

It is unclear why they stayed around twice as long as stipulated, but the military recognised in a document that there were "delay(s) in the evacuation of rehabilitated clients".

The four men's overall experiences could influence what happens to others still with the insurgents.

According to USAID which interviewed more than 100 graduates of the programme, half said they had been in touch "with former peers still affiliated with BH-ISWAP".

So, what awaited the men after all the time spent in detention facilities and undergoing the deradicalisation programme?

After swearing an oath of allegiance to the Nigerian state and promising not to return to fight, internees are generally given around 20,000 naira each (about $50, 42 euros) and sent to another transit centre before being released.

"Links with communities are made before graduates return," Nwachukwu said, adding the programme continued to monitor them.

Once released, state authorities are responsible for their reintegration.

When Mallam was reunited with his wife after nearly five years away in total, hunger had changed her completely.

"She had been living in a camp where there is no food at all... My parents died and all our children are malnourished."

Even Aliyu and Muhammad, who fit the low-risk criteria and received amnesty through the programme, questioned its ultimate impact.

Now earning less than a euro (dollar) a day and shunned by many, they are reluctant to encourage others to surrender.

"They told us about employment, but in the end there are no jobs," said Muhammad, whose new life is more difficult than he had imagined.

"What type of life is this?... I regret surrendering."

Several charities and the IOM help reintegration efforts which can fuel resentment among residents whose lives are still upended by war.

As the insurgency enters its 12th year, the United Nations warns that 4.3 million people are food insecure in the northeast.

"Reintegration efforts are commendable... but there is a lot of animosity, people are angry," said Mariam Oyiza, who heads a small charity supporting women affected by violence.

In the hope of ending the war and with hundreds of defections in recent weeks, the federal government and donors are banking on the programme.

But to reach its potential, Nigerian authorities must show that they "can guide internees to graduation and reintegrate them back into society safely and securely," the Crisis Group said.

"To date, Safe Corridor falls short of being able to offer those kinds of assurances with sufficient credibility."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.