Obama Administration Supports Amazon In Supreme Court Warehouse Worker Case

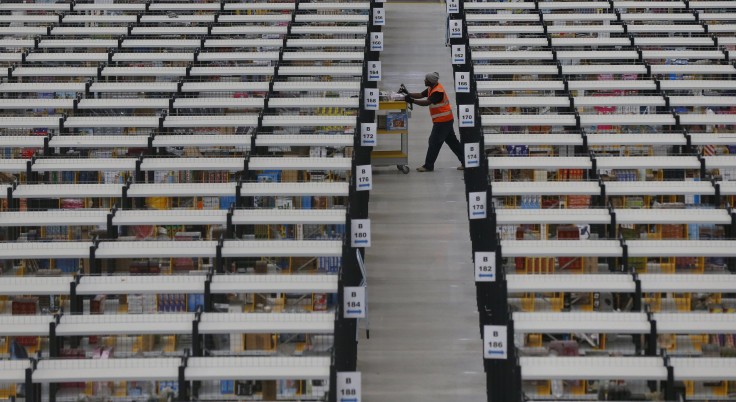

The U.S. Supreme Court begins hearing arguments Wednesday about whether Amazon’s warehouse workers should be paid for time spent undergoing mandatory security checks. The decision will have sweeping implications for hundreds of thousands of workers across the country.

One part of the proceedings, however, has many experts baffled: The Obama administration, known for fighting for minimum wage and workers’ rights, has come out in support of Amazon and Integrity Staffing Solutions Inc., the contracted employers.

“The administration’s position in this case runs exactly counter to its avowed goal of raising workers’ wages,” Robert Reich, who served as Labor Secretary under former President Clinton and is now a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, told International Business Times. “I’m frankly surprised the Obama administration is siding with the employers here,” he said.

The case has been working its way up to the Supreme Court for four years. It started when Jesse Busk and Laurie Castro, former Amazon warehouse workers in Nevada, filed a complaint against their contract employer, Integrity Staffing Solutions, arguing that employees should be compensated for the time they spent undergoing checks to ensure they hadn’t stolen merchandise from the workplace. The screenings can take up to 25 minutes.

Amazon, for its part, has previously told reporters that employees “walk through post-shift security screening with little or no wait.”

“I’m sure there are a lot of subtexts, but the facts are really not in dispute,” Mark Thierman, Busk’s attorney, said to IBTimes. “The question is whether or not it's work.”

U.S. law dictates that workers must receive pay for the time they spend in the workplace preparing for their duties, which can include putting on specialized clothing and protective gear. It can also include the time workers spend showering after a shift to clean off hazardous manufacturing materials. Both are essential functions of particular jobs, but Integrity and Amazon argue that waiting in line to be screened isn't essential to a warehouse worker's duties and therefore should not be compensated.

The Nevada District Court initially dismissed Busk and Castro’s case, but they appealed and won in the Ninth Circuit. Integrity appealed the decision, and now it falls to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In June, the Obama administration filed a brief, arguing that “the judgment of the court of appeals should be reversed.”

While amicus curiae briefs aren't legally binding, recent research shows that they are increasingly having more impact on Supreme Court decisions.

“I just don’t get why the Department of Labor came out on the side of Integrity in this case,” said Paul Secunda, director of the labor and employment law program at Marquette University Law School.

Most Amazon warehouse workers earn minimum wage or slightly more, which means between $8 and $14 per hour, according to Forbes. The workers are asking for back payments to compensate for time spent in line. While 25 minutes in line doesn’t seem like a great deal, when multiplied by thousands of workers the cost could be significant.

“There are billions of dollars at stake,” Secunda said. “It may seem cynical, but I can see this as something that large corporate donors to the Democratic Party care deeply about.”

Amazon's political sway and campaign donations may not provide answers. The company donates to both major political parties in roughly equal amounts. So far in 2014, the Amazon Corporate LLC Separate Segregated Fund PAC has contributed $300,778 to political parties, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Of the total, 53 percent of the political action committee's donations went to Republicans, and 47 percent went to Democrats. In 2012, 52 percent went to Democrats.

“What makes this case unique is that we have all this debate in the country about what minimum wage should be, but here we are decades later, litigating when does work time begin and end,” David Garrison, attorney at a Nashville-based firm that represents hundreds of warehouse workers in similar claims, told IBTimes. He explained that some of the major issues at play are based on the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

“I don’t think that in 1938 that Congress could imagine a million-square-foot warehouse that’s controlled this way by an employer,” Garrison said. “This decision has a potentially tremendous impact.”

The U.S. Supreme Court began hearing arguments at 10 a.m. EDT on Wednesday morning.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.