Oldest Primate Fossil Skeleton Found: Archicebus Achilles Could Shine Light On Human Evolution

The oldest primate ever discovered would fit in the palm of your hand, snacked on bugs and had some seriously big feet.

On Wednesday, scientists announced the discovery of what they’re dubbing Archicebus achilles in a paper published in the journal Nature. The first part of the primate’s name means “beginning long-tailed monkey,” the second references both the ancient Greek warrior and the creature’s unusual heel anatomy (more on that later). The 55 million-year-old fossil, 7 million years older than the oldest previous find, was discovered on a lake bed in China’s Hubei Province that’s more well-known for producing fossil fish than for turning out preserved tiny primates.

As the earliest primate fossil ever discovered, Archicebus fills in an important branch on the primate evolution tree, where early primates diverged into the lineage that led to monkeys, apes and humans – also known as the anthropoids – and Tarsiiformes, the group that has just one living representative, the tarsiers. And it’s a remarkably well-preserved specimen.

“Normally we just find a few teeth, or a jaw,” coauthor and Northern Illinois University researcher Daniel Gebo said in a phone interview. “What makes this fossil particularly interesting is its completeness.”

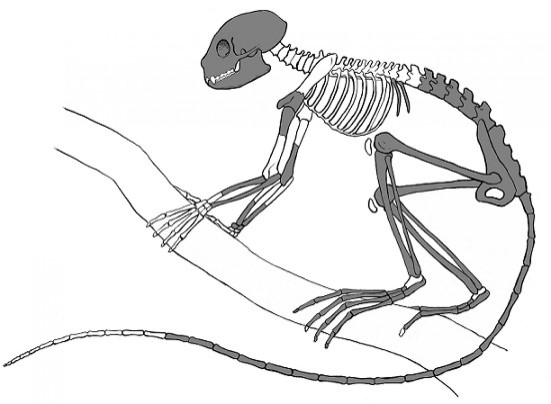

The Archicebus specimen that died in an ancient lake millions of years ago was a tiny little thing – a little under three inches long, not counting its 5-inch long tail. Based on Archicebus’s teeth shape and body size, the researchers think this little creature dined on fruit and insects. It had very long legs designed for leaping, and hands and feet perfectly suited to grasping branches. It probably spent most of its day moving around among the trees, looking for food.

“Small primates and small animals in general have very high metabolic rates, so they need a lot of calories quickly,” Gebo said. “A little animal like this one basically needs candy bars – like how hummingbirds are basically mainlining sugar.”

But it’s Archicebus’s foot, which is about one-third the length of its leg, that's especially interesting to researchers. Though it has the arms, legs, skull and teeth of a very primitive primate, its feet are closer to a modern monkey’s, with elongated metatarsals – the “palm bones” of the foot. Tarsiers also have long feet, but they have elongated heel bones, not long metatarsals.

Scientists are calling Archicebus a very, very early member of the tarsier lineage, arising very close to the evolutionary divergency that gave rise to that line and the anthropoid families. But the presence of seemingly "modern" features attached to Archicebus's more primitive body type may cause scientists to rethink some assumptions about primate evoultion. The feet of apes and monkeys might not be a more recent adaptation, but rather the persistence of an earlier evolutionary design.

“The feet of anthropoids may be the primitive condition,” Gebo said.

The fact that Archicebus was found in China also lends some weight to an emerging theory that primates themselves may have originated in Asia, not in Africa, as previously assumed. While humans definitely arose in Africa, our arboreal ancestors may actually be from a very ancient China.

“If you look at Africa today, the most primitive primates living – lemurs, galagos [also known as bush babies] -- live there,” Gebo said. “But the fossil primates we keep finding in Asia end up being more and more primitive.”

An Asian origin for primates actually makes a great deal of sense, Gebo said. Two of the mammal lineages most closely related to primates – tree shrews and flying lemurs -- are both Asian mammals.

Uncovering the fossil itself was no easy task. Xijun Ni, the lead author of the paper and a researcher with the American Museum of Natural History and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, persuaded a local farmer to donate the rock containing the fossil to researchers. The rock, once it was split in half, had most of the fossilized bone on one side and a mirror-image cast on the other. To fully reconstruct the specimen, researchers from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility used advanced CT scanning to create a three-dimensional digital model of Archicebus.

“This new technology allows us to digitally reconstruct the specimen, so you can see the secret hiding in the rocks,” Ni said.

SOURCE: Ni et al. “The oldest known primate skeleton and early haplorhine evolution.” Nature published online 5 June 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.