Omega Centauri, Milky Way’s Largest Globular Star Cluster, Unlikely To Host Life

Astronomers have ruled out a major chunk of stars from the list of Milky Way candidates that could possibly host life-brewing worlds in their proximity.

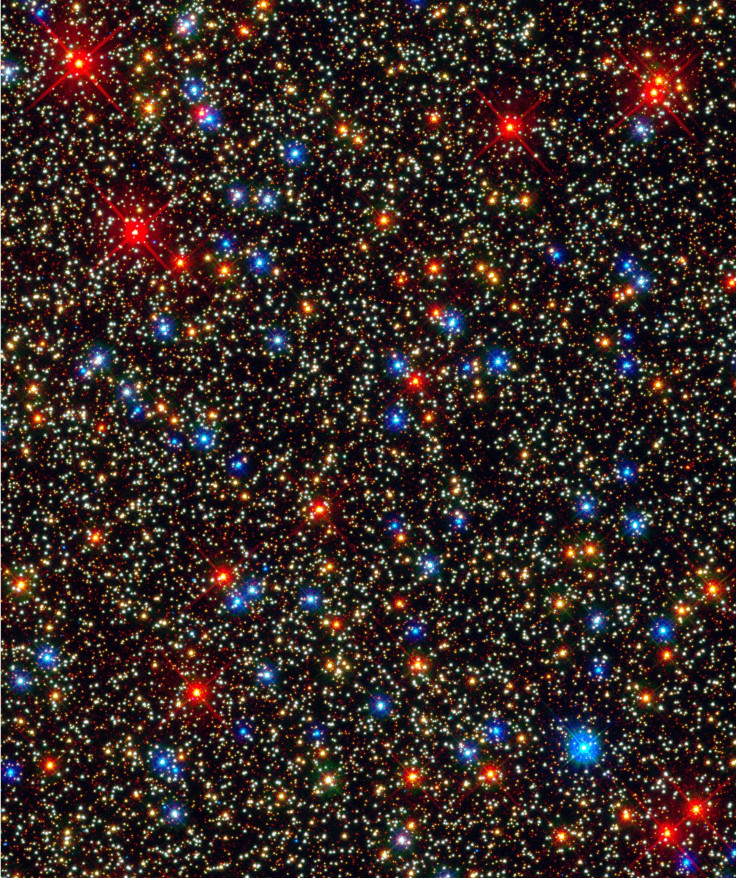

The chunk, officially named Omega Centauri, is a densely packed globular cluster with an estimated 10 million stars. It sits some 16,000 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Centaurus and has been a point of observation for decades, primarily due to its humongous size.

Omega Centauri stars span across 150 light years and weigh nearly as much 4 million Suns. This led many to think that some of these stellar bodies could have exoplanets in the so-called "Goldilocks zone" — the region where a world is far enough from its star to have liquid water on its surface and possibly life, like Earth.

“Since this type of compact star cluster exists across the universe, it is an intriguing place to look for habitability,” lead author Stephen Kane from the University of California, Riverside, said in a statement. However, "despite the large number of stars concentrated in Omega Centauri's core, the prevalence of exoplanets remains somewhat unknown".

So, Kane and colleagues started exploring the case of habitability in Omega Centauri. They first looked at the temperature and age of nearly 500,000 stars sitting in the core of the cluster. The analysis revealed almost 70 percent of those bodies had suitable conditions to have planets in the habitable zone.

"The core of Omega Centauri could potentially be populated with a plethora of compact planetary systems that harbor habitable zone planets close to a host star," Kane added. "An example of such a system is TRAPPIST-1, a miniature version of our own solar system that is 40 light years away and is currently viewed as one of the most promising places to look for alien life."

But, as most of the stars in cluster’s core were cool, small Red Dwarfs, the researchers estimated their habitable zone planets would be much closer than what we see in our own Solar System. This, as the researchers described, affects the case of life in the cluster.

Essentially, the densely packed arrangement of stars in Omega Centauri’s core would mean that the bodies would interact with their neighbors from time to time. The forces generated from such encounters would be too much to sustain any form of microbial life on planets in their habitable zones.

"The rate at which stars gravitationally interact with each other would be too high to harbor stable habitable planets," study co-author Sarah Deveny added in the statement. Numerically speaking, the average distance between stars in the cluster's core is just 0.16 light-years, which means they would make a close pass once in a million years. This is a lot quicker than what our Sun, which sits some 4.22 light years away from its closest neighbor, experiences.

"Looking at clusters with similar or higher encounter rates to Omega Centauri's could lead to the same conclusion," Deveny concluded. "So, studying globular clusters with lower encounter rates might lead to a higher probability of finding stable habitable planets."

The study titled, "Habitability in the Omega Centauri Cluster," will be published in The Astrophysical Journal and arXiv paper and be available online.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.