Peace Is A Tall Order In Massacre-hit Mali Village

In Ogossagou, where ethnic Fulani suffered two massacres in two years, traces of the recent horrors abound in this village of central Mali.

They are one sign of just how tough incipient internationally-sponsored peacemaking efforts are between nomadic Fulani herders and traditional Dogon hunters.

Reconciliation is all the more difficult as the Dogon accuse the Fulani of supporting the jihadists -- who are now present in central Mali but have been a scourge of the Malian government and its western allies since 2012.

A peace pact signed last month has produced "a lull" in the village, Senegalese army captain Andre Sebastien Ndione, who heads the nearby UN base, told AFP.

"But it is relative, it can go off the rails at any time," Ndione added.

In the Fulani part of the village, targeted by people dressed as traditional Dogon hunters, reminders are everywhere of the killings of 160 civilians in March 2019 and 31 more in February 2020. Local NGOs say the number of Fulani dead is even higher.

Destroyed houses lie abandoned in tall grass and a charred wooden pestle for grinding millet bears witness to the brutality of the events.

Ogossagou is one of the last villages in central Mali's Bankass area where Fulani, who are also called Peul, still live.

Ghost villages are all that remain in other parts of the area.

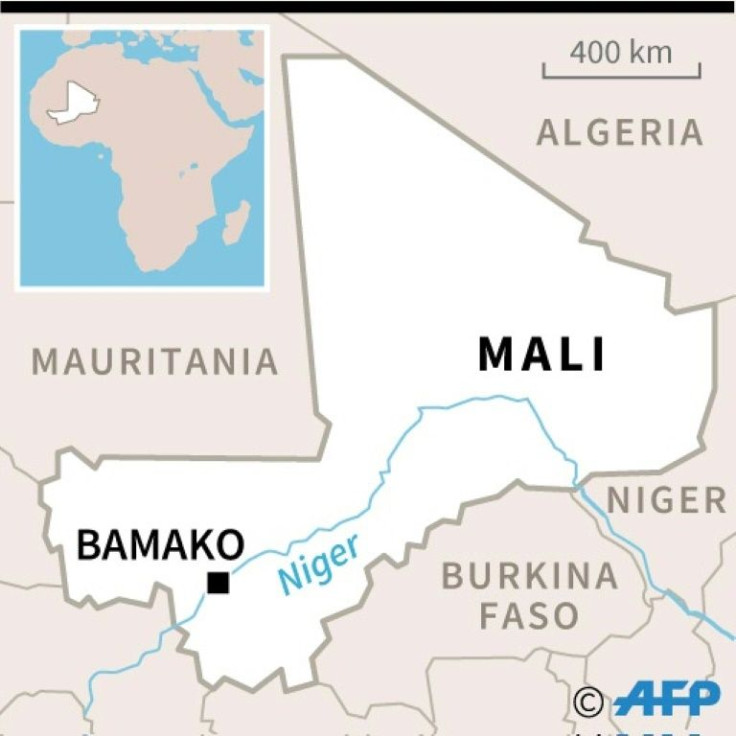

A hotbed of violence plaguing the Sahel, the centre of Mali has become prey to the atrocities of jihadist organisations, self-defence groups, brigands and even regular armed forces.

Both Malian and UN security forces have been singled out for their inability to prevent the repetition of violence that weighs heavily on people's minds in Ogossagou.

Malian soldiers and peacekeepers of the UN MINUSMA operation are today based between the districts of Ogossagou-Dogon and Ogossagou-Peul, separated by a few dozen metres that might as well be thousands of metres given the gulf in feeling.

The Fulani, living next to mass graves dug in haste, are constantly bullied by Dogon neighbours who accuse them of being accomplices of the Al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadist group in the area.

The Fulani wanted to leave Ogossagou after the second massacre, but troops restrained them in the months that followed the slaughter on February 14, 2020.

"The army prevented people from fleeing. It would have been a failure for the state if there were no more Fulani," a humanitarian source in the region told AFP on condition of anonymity.

Government soldiers have also been accused by the United Nations of raping Fulani women who survived the massacres.

The year 2020 was a long one for the Fulani. Nobody could leave the village to cultivate their fields or go to the market.

Residents were too afraid of being killed to take to the road, despite the peaceful appearance of the bush that surrounds Ogossagou and stretches to the horizon.

"It was an open-air prison," said Jens Christensen, the Danish regional director of MINUSMA.

Tensions ran so high that in March the soldiers had to intervene to separate Dogons and Fulani when a Dogon's dog strayed from one part of the village to another.

In September 2020, Christensen and his teams began a step-by-step mediation, which culminated on October 8 with the signing of a peace agreement.

It bound inhabitants of Ogossagou and ten surrounding villages to lay the foundations for reconciliation, specifying that Fulani and Dogon visit each other, accept free movement and not attack each other.

The bright smiles of village children lighten the ambient gloom, but they are not enough to eradicate the deep fissures in the village.

To be sure, Dogon and Fulani representatives sat down at the same table to meet the head of MINUSMA, Mauritania's El-Ghassim Wane, credited by the United Nations with 25 years of experience in conflict prevention.

The talks were "something unimaginable for three years", Christensen said. Fulani farmers were also able to plant millet seeds in their fields surrounding Ogossagou for the first time since 2017.

In front of Wane, who heard unanimous thanks given to the United Nations, old grudges surfaced.

A Dogon leader warned his people will not be held responsible if people from 'elsewhere', and therefore not signatories to the agreement, attack again.

A Fulani leader meanwhile complained of not having been greeted when he went to visit the Dogon district.

Some houses were rebuilt by the Fulani in other villages to facilitate the return of those who had sought refuge in Ogossagou for fear of being attacked. But they were immediately burned.

People seeking justice for the massacres have seen little if any progress.

"While the situation is not yet completely stabilised, it is obvious that it has changed a lot," argued the head of MINUSMA.

Wane decided to "maintain for the moment" the presence of a temporary UN base.

Elsewhere in Mali, such bases are established for a few weeks or months. In Ogossagou, the base will have been here for two years by February 2022.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.