Pedro Castillo, Rural Teacher With A Shot At Peru's Presidency

Rural school teacher Pedro Castillo was largely unknown in Peru until he led a nationwide strike four years ago.

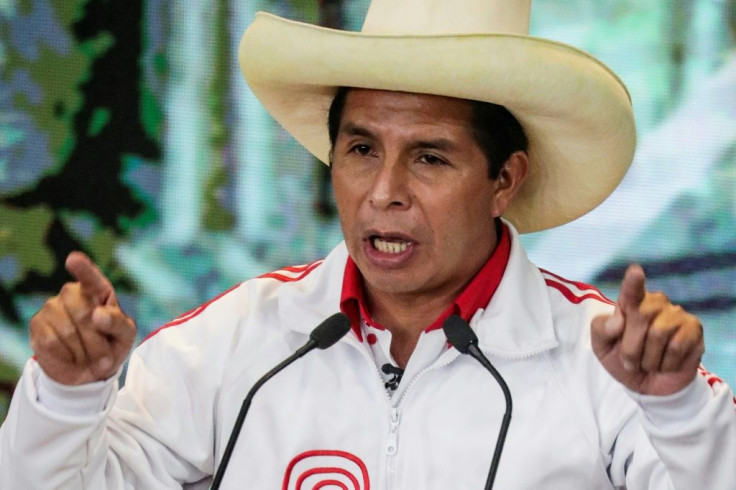

Now the 51-year-old far-left unionist, rarely without the trademark white, wide-brimmed hat of his home region of Cajamarca, has a chance to become Peru's next president.

Facing off against neoliberal Keiko Fujimori in elections on Sunday, Castillo has vowed to nationalize Peru's vast mineral resources, to expel foreigners who commit crimes in the country, and to move towards reinstating the death penalty.

One thing unlikely to change under a Castillo presidency is the Peruvian state's socially conservative character: he is Catholic and vehemently opposed to gay marriage, elective abortion and euthanasia.

He frequently quotes from the Bible to drive home his points.

In April, Castillo surprised many by taking the lead in the race to become Peru's fifth president in three years.

He had not ranked among the top five choices in opinion polls ahead of a first voting round contested by a record 18 candidates.

Yet Castillo garnered nearly 20 percent of ballots cast amid a raging Covid-19 outbreak to which he also fell victim when he contracted the virus last year.

A poll issued a week ahead of Sunday's vote showed Castillo leading with 42 percent of voter intention, compared to 40 percent for Fujimori.

Castillo burst onto the national scene four years ago when he led thousands of teachers on a nearly 80-day strike to demand a pay rise and the repeal of an unpopular system for evaluating teacher performance.

The strike left 3.5 million public school pupils without classes to attend, and compelled then-president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who initially refused to negotiate, to relent and agree to striker demands.

In a bid to delegitimize the protest, then-interior minister Carlos Basombrio claimed its leaders were linked to Movadef, the political wing of the defeated Shining Path Maoist guerrilla group dubbed a "terrorist" organization by Lima.

Castillo, who had participated in armed "peasant patrols" that resisted Shining Path incursions during the height of Peru's internal conflict from 1980 to 2000, vehemently rejected these allegations.

He was born in Puna, a town in Cajamarca, where he worked as a rural school teacher from the age of 24.

He almost always wears Cajamarca's traditional hat, likes to don a poncho and shoes made of recycled tires, and arrived on horseback -- the region's traditional means of transport -- to cast his vote in the first round.

"I come with clean hands, I am a man of work, a man of faith, a man of hope," is how he recently described himself.

On the campaign trail for the Free Peru party, Castillo promised radical change to improve the lot of Peruvians contending with a recession worsened by the pandemic, rising unemployment and poverty.

He has targeted creating a million jobs in a year, denying that he intends to confiscate workers' pensions, as his critics claim.

"We are not going to take savings from the people who work, we will respect private property... workers own their savings," he said.

But Castillo has said that Peru's mining and hydrocarbon riches "must be nationalized."

Peru is a large producer of copper, gold, silver, lead and zinc, and mining brings in 10 percent of national GDP and a fifth of company taxes.

Castillo has promised public investment to reactivate the economy through infrastructure projects, public procurement from small businesses, and to "curb imports that affect the national industry and peasantry."

But he has sought to dispel claims that "we are going to take your wine farm, that we are going to take your house, your property."

Among his more controversial campaign promises, Castillo has vowed to expel illegal foreigners who commit crimes in Peru, giving them "72 hours... to leave the country."

The comment was perceived as a warning to undocumented Venezuelan migrants who have arrived in their hundreds of thousands since 2017.

Free Peru is one of few left-wing Peruvian parties to defend the regime of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, whose 2018 re-election is not recognized by more than 50 countries.

To combat crime, Castillo has proposed withdrawing Peru from the American Convention on Human Rights, or San Jose pact, to allow it to reintroduce the death penalty.

On social matters, he has made his position clear.

"I would not at all legalize abortion and, worse still, gay marriage," he told RPP radio in April.

If elected, Castillo has said he would renounce his presidential salary and continue living on his teacher earnings.

His wife joined him for the first time at a campaign event during a closing rally Thursday, where Castillo urged his supporters to be "vigilant" throughout the vote-counting process on Sunday.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.