How Republicans Protect Anonymous Donors And Their ‘Dark Money’ Groups

Lawmakers in the current Congress have slipped language into two spending bills to protect so-called “dark money” nonprofits from IRS scrutiny. The provisions prevent the IRS from examining or defining the nebulous rules that govern those groups, which are not required to disclose their donors. Critics say those groups are taking advantage of a broken campaign finance system — and charge that Republicans in both Congress and the Federal Elections Commission are making sure the system doesn’t get fixed.

“Dark money” is a term used to describe spending by nonprofit “social welfare” organizations, usually 501(c)(4) organizations, which are named after the section of the tax code that created them. They are called “dark” because they don’t have to disclose their donors, due to a 1958 Supreme Court decision that ruled the NAACP didn’t have to disclose its donors to the state of Alabama. The groups enjoy tax-exempt status because they purportedly engage in activity that benefits society as a whole, hence the “social welfare” designation.

Read: Trump Supporters Pay For Comey Attack Ad Through ‘Dark Money’ Group

Those who defend the practice on free speech grounds believe the term “dark money” is sensationalist, and argue that it accounts for less than five percent of total campaign spending.

A 501(c)(4) can engage in politics and still maintain its tax exempt status so long as politics is not its “primary activity.” Traditionally, that’s been interpreted to mean that a 501(c)(4) group can’t spend more than than half of its resources on politics, but the rule has never been clearly defined and critics say the ambiguity has led to abuse in the form of groups that spend the majority, if not all, of their time and money on politics, without repercussions.

While the IRS has tried to clarify the classification, Congress has prevented it from doing so, citing the 2013 IRS scandal that arose from the agency’s flawed handling of a deluge of new 501(c)(4) groups in the aftermath of Citizens United. As a result, the spigot of money from anonymous-donor groups has stayed open.

At the same time, the other mechanism for regulating money in politics, the Federal Election Commission, has been locked in partisan gridlock and unable to enforce its own rules, according one of the FEC’s six commissioners who resigned in February.

Editorial: Ann Ravel and the FEC’s appalling dysfunction https://t.co/kKF3tN0ZnS pic.twitter.com/h3fEIbAzSN

— Mercury News (@mercnews) February 24, 2017

“There are two separate ways this problem of secret money in elections can be addressed,” Daniel G. Newman, president and co-founder of Maplight, a nonpartisan money-in-politics watchdog, told International Business Times. “Either through the FEC, which is dysfunctional, or the IRS, which is not taking action.”

Newman said the language inserted into recent spending bills are “closing off any avenues for making secret money transparent.”

The result is a system awash in money from anonymous donors, experts say.

“The reality seems to be that there just isn’t much enforcement,” Ian Vandewalker, a campaign finance expert at NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, told IBT. There are many examples of documented cases where dark money groups spent more than half of their time and money on politics, Vandewalker asserted, but no penalties were levied by either the IRS or FEC. “Enforcement just isn’t there,” he said.

While most of the more than 80,000 501(c)(4) groups active in the U.S. aren’t making campaign ad buys, total political spending by these groups has increased dramatically over the last decade, from $1.26 million in the 2006 election cycle to a high of $257 million in 2012, to $145 million in 2016, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In state elections, where total spending is much lower, dark money makes up a much larger percentage of total expenditures. Last year, the Brennan Center for Justice studied dark money expenditures in six states between 2006 and 2014, and found that, on average, 76 percent of outside spending was fully transparent in 2006. That number dropped to 29 percent in 2014.

The numbers on anonymous spending are probably underreported, political analysts say, because dark money groups have become expert at cutting back spending once the FEC’s pre-election mandatory disclosure period begins. They also skirt FEC rules about “political speech” by not explicitly endorsing a candidate in supportive ads, or not expressly urging voters to reject candidates targeted in attack ads. By avoiding FEC disclosures, which sometimes must be filed within 24 hours of an expenditure, these groups have to file only once a year with the IRS.

“Regardless of the research and speculation, you're left with a situation where you don't really know what is going on, because not enough is disclosed,” Newman told IBT. “Which is dark money in a nutshell.”

These groups aren’t active only during campaign season. In recent months, 501(c)(4) groups ran ads attacking former FBI director James Comey during his Senate testimony, ads both supporting and attacking Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch during his confirmation process, and just last week ran ads criticizing Sen. Dean Heller, R-NV, for his decision not to support the Senate health care bill. Because the ads were bought by 501(c)(4)s, instead of, say, super PACs, which are required to disclose their donors, the funders of these millions of dollars worth of ad buys remain anonymous.

Last week, as some Republicans bemoaned ads attacking Heller, Rep. Tom Graves, R-GA, chairman of the House Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government, introduced a draft of this year’s Financial Services Improvement Act. That bill contained language that prevents the IRS from using any of its funding to review how it evaluates 501(c)(4) groups.

“None of the funds made available in this or any other Act may be used by the Department of the Treasury, including the Internal Revenue Service, to issue, revise, or finalize any regulation, revenue ruling, or other guidance not limited to a particular taxpayer relating to the standard which is used to determine whether an organization is operated exclusively for the promotion of social welfare for purposes of section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986,” the bill reads.

The bill also contained a provision that mirrored an executive action taken by President Donald Trump to curtail enforcement of the Johnson Amendment, which prevents another kind of nonprofit, the 501(c)(3) group that includes churches, from participating in politics. Graves’ office did not respond to questions about the language or why it was added to the bill.

New House Appropriations bill has a rider barring IRS & US Treasury from making "bright line" rules on 501(c)(4) political nonprofits, again pic.twitter.com/oH4Q8LYpOy

— Anna Massoglia (@annalecta) June 29, 2017

That exact same 501(c)(4) enforcement language was also included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, which President Donald Trump signed into law earlier this year. A spokesman for Rep. Paul Cook, R-CA, who sponsored the bill, said the language did not come from Cook. The language was requested by several GOP senators, according to an aide to the Appropriations Committee.

“501(c)(4)s have emerged as one of the primary ways to make enormous donations and influence elections without having to disclose donors,” John Wonderlich, Executive Director of the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan nonprofit dedicated to government transparency, told IBT. “Measures like this one are pretty clearly intended to protect 501(c)(4)s in their roles as essentially money launderers for political donations.”

While Congress is preventing the IRS from examining the rules governing the groups’ tax exempt status, the FEC is also being prevented from fulfilling its duty to regulate campaign finance and hold dark money groups accountable, according to former FEC commissioner Ann Ravel who resigned in February and slammed the Commission on her way out the door.

“A bloc of three Commissioners routinely thwarts, obstructs, and delays action on the very campaign finance laws its members were appointed to administer,” said a report prepared by former commissioner Ravel’s office. Ravel was one of three Democratic commissioners on the six-member board, which is split between Democrats and Republicans. The bloc Ravel charged with obstructing the FEC's work are all Republicans.

“Due to the bloc’s ideological opposition to campaign finance law, major violations are swept under the rug and the resulting dark money has left Americans uninformed about the sources of campaign funding,” the report said. It pointed out that in 2006, the six-member Commission deadlocked 3-3 in just 2.9 percent of votes on enforcement cases, but that number rose to 30 percent of all enforcement actions in 2016.

One of those deadlocked decisions was the case of Carolina Rising, a 501(c)(4) that spent 97 percent of its revenue on running 4,000 ads praising Republican senate candidate Thom Tillis, who won North Carolina’s junior senate seat in 2014. In total, the group spent $4.7 million on the ads, which were funded from $4.82 million in contributions from a single anonymous donor.

Because the FEC was deadlocked with a 3-3 vote, the Democratic party’s complaint against Carolina Rising was dismissed.

While anonymous-donor groups can support both Republicans and Democrats, Republicans seem to benefit more from the practice. Last election cycle, political spending by all 501(c) groups, which include 501(c)(6) groups like chambers of commerce, business leagues and trade boards, as well as 501(c)(5) labor organizations, favored Republicans over Democrats, $140 million to $64 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In 2012, the gap was even greater, $270 million to $58 million.

The Scandal That Sidelined The IRS

The language included in both this year’s spending bills isn’t new. It’s been included in several appropriations bills over the last few years, but it didn’t become law until the previous Congress sent its 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act to President Barack Obama, who signed the bill into law at the end of 2015.

The first bill to include the language was the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2015, which never made it to the president’s desk. That bill was introduced in July 2014 by former House Appropriations Financial Services Subcommittee chair Rep. Ander Crenshaw, R-FL, in response to the 2013 IRS scandal that arose from the IRS’s examination of conservative 501(c)(4) groups.

The controversy resulted in several high-ranking officials, including the acting commissioner, leaving the IRS after a May 2013 audit by the Treasury inspector general found that the IRS had used “inappropriate criteria” to determine whether a group was engaging in political speech, but found no evidence of political bias. A congressional investigation was unable to come to a consensus on whether the IRS had acted unfairly, with Republican investigators releasing a report saying conservative groups were improperly targeted, while Democrats said the IRS had simply bungled its efforts to process the huge growth in 501(c)(4) groups.

Now retired from Congress and working as a senior counsel at a leading lobbying firm, Crenshaw told IBT the language was added in response to the scandal, and the IRS’s attempt to come up with new rules governing the agency in the aftermath, an attempt that generated more public comments than any proposed rule in the history of the Treasury department.

“I think the purpose of [the bill’s language] was to say ‘you guys wasted a lot of money, done a lot of bad things, you should get back to the core mission of the IRS and stop meddling in politics,” Crenshaw told IBT.

But the reason the IRS, a tax collection bureaucracy, was involved in figuring out how to classify nonprofit speech is because Congress forced it to do just that when it passed the law that created 501(c)(4) groups, said John Pomeranz, an attorney with Harmon, Curran, Spielberg + Eisenberg LLP who specializes in laws governing nonprofits’ election-related activity.

“The IRS has never defined what is or what is not political and how much of it the 501(c)(4)s could do without jeopardizing their tax exempt statuses,” Pomeranz told IBT. “A lot of this would be solved if Congress would allow the IRS and Treasury departments to do their jobs.”

Much of the confusion around these groups stems from Congress’ failure to address the effects of Citizens United. That 2010 Supreme Court decision famously opened the door to unlimited political spending by corporations and unions, but less famously also upheld donor disclosure rules. Some observers have argued that the Justices decided Citizens United the way they did because they assumed the money it was unleashing would not be anonymous.

“A campaign finance system that pairs corporate independent expenditures with effective disclosure has not existed before today,” Justice Kennedy wrote in his majority opinion in the case. “The First Amendment protects political speech; and disclosure permits citizens and shareholders to react to this speech of corporate entities in a proper way. This transparency enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.”

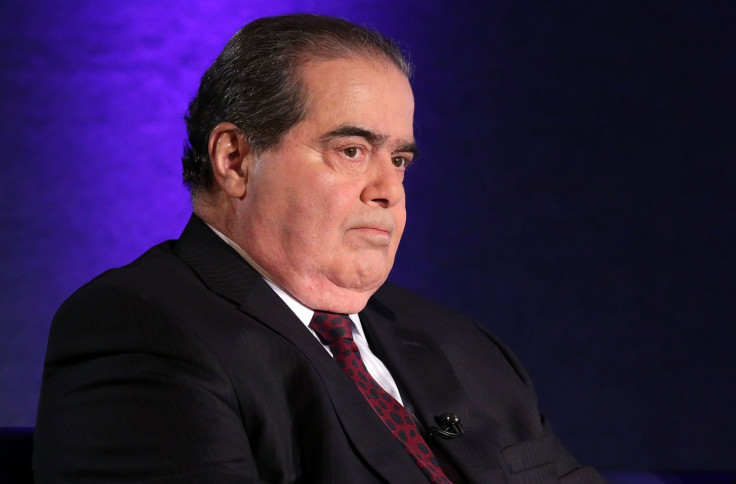

It’s not clear if the Supreme Court anticipated the rise of 501(c)(4) groups as vehicles of political spending divorced from disclosure requirements. Dark money groups insist that they must keep their donors secret to protect them from harassment, an idea that the late Justice Antonin Scalia once rejected in favor of “requiring people to stand up in public for their political acts,” which “fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed.”

After Citizens United, several bills were introduced in Congress to force dark money groups to disclose their donors. In 2010, Senate Republicans blocked the DISCLOSE (Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections) Act after it passed the House, resulting in a defeat celebrated by the ACLU on free speech grounds. The act was a comprehensive response to the Citizens United ruling, and among other provisions, required groups making independent campaign expenditures to disclose donors who contributed more than $10,000. Subsequent DISCLOSE Acts were introduced by Democrats in every Congress since, including the current Congress. None of them reached the floor of either chamber for a vote.

At the same time, Republicans introduced the Stop Targeting of Political Beliefs by the IRS Act of 2015, which required the IRS to not change their rules about tax-exempt organizations from what they were on Jan. 1, 2010. That bill also failed to reach the floor.

But the efforts to change the rules continue. In May, Rep. Michelle Lujan Grisham, D-NM, introduced the 501(c)(4) Reform Act of 2017, which would prevent any 501(c)(4) group from participating in political campaigns either for or against candidates. The bill has no co-sponsors and is unlikely to be voted on.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.