There's A Direct Link Between Tax Evasion And Income Inequality

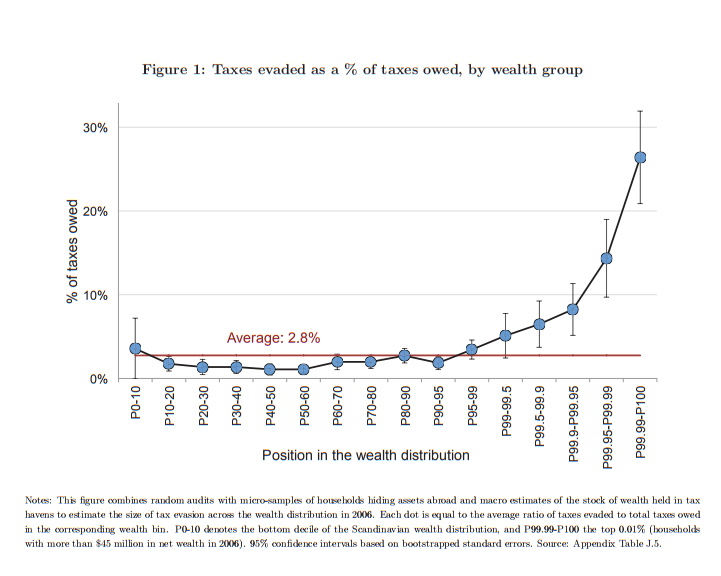

The ultra-wealthy are ultra-wealthier than they may appear — at least, to their respective tax authorities. That’s because, perhaps unsurprisingly, those who exploit offshore tax shelters are not likely members of the average household, but rather those in the top one percent of the one percent of income distribution, a trend that’s increasingly concealed the severity of wealth-inequality over the past several decades, according to two studies published this week.

Using leaked information — namely, the Panama Papers and files from the British bank HSBC — about overseas tax havens and the individuals who exploited them, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and the University of Copenhagen found that “top 0.01 percent households are much more likely to hide assets abroad than households in the bottom of the top 1 percent.” More specifically, a household with a net worth of between $10 million and $12 million is twice as likely as one with between $5 million and $6 million to hide its wealth abroad. Increase those household assets from the latter range to about $45 million, and the likelihood of offshore tax sheltering also rises. by a multiple of four.

“Offshore wealth is very concentrated at the top,” said Annette Alstadsæter, a professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and one of the three authors of the two studies. She called the results “striking,” and emphasized the importance of using new information on tax sheltering to craft effective public policy, as, thanks to such leaks as the Panama Papers, “one can hope that there isn’t much of a safe harbor for offshore tax evasion anymore.”

The reason for the concentration of the hidden wealth among the super-rich may have more to do with a supply of specialists who can help them hide their wealth in places like Switzerland and the Cayman Islands, rather than demand for such services. As the authors point out, “taxpayers with more than $50 million in wealth face the same marginal tax rates as those with $5 million, are more likely to be (non-randomly) audited and yet seem to evade much more.” But because banks that offer tax avoidance services are more likely to be caught when they offer those services to a larger swath of clients, the researchers suggest, “it is optimal for banks to only supply tax evasion services to the super-rich.”

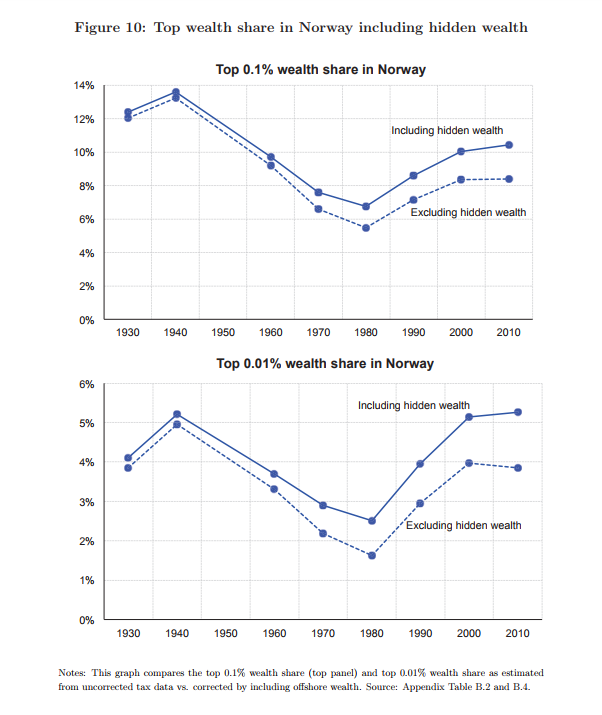

The gap between the total wealth held by the top earners and the assets they disclosed domestically has widened substantially over the past several decades, the study also noted. In Norway, for example, the difference between the assets that the top 0.01 percent disclosed and those individuals’ true total assets, both hidden and disclosed, as a share of the country’s total wealth grew to nearly 1.5 percent in 2010 from roughly three-quarters of a percent in 1970 and an almost negligible amount in 1930.

The authors’ estimates may even skew conservative, as the paper examined only Scandinavian countries, which, they wrote, citing earlier research, “consistently rank among the countries with the highest social trust, lowest corruption and strongest respect for the rule of law.” Tax evasion among the highest earners, they concluded, “may be even higher elsewhere.”

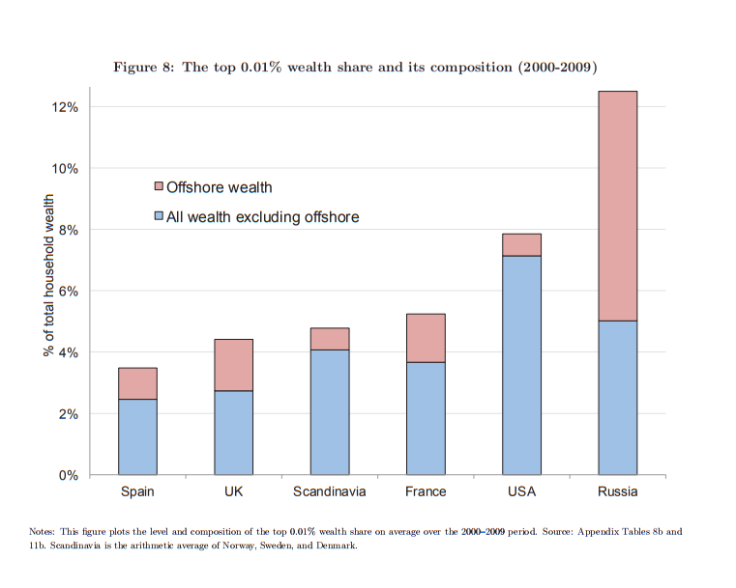

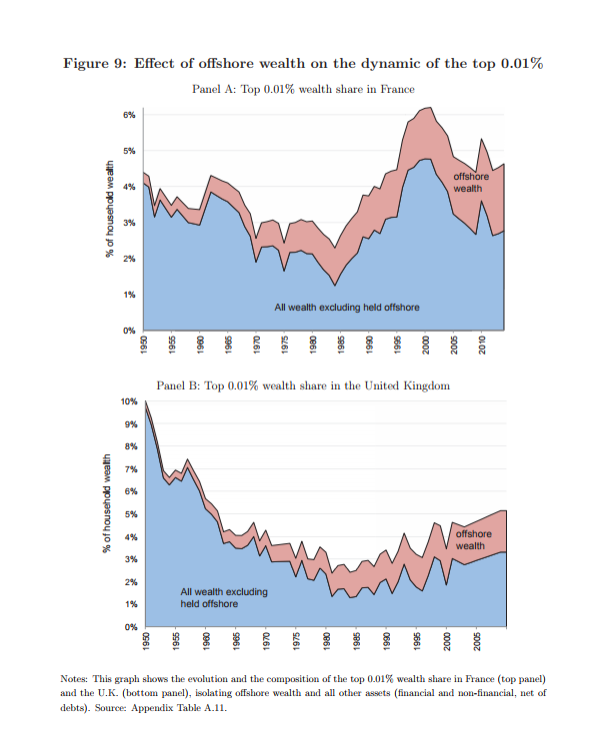

In a second study, also published this week, they sought to add some certainty to that presumption, calculating what they described as the first “country-by-country estimates of offshore wealth” and measuring the effects of foreign tax sheltering on inequality. The impact was most acute in Russia, where the top 0.01 percent held more wealth offshore than they did domestically. Similarly, in some of Europe’s economic powerhouses, such as the U.K. and France, between 30 and 40 percent of the wealth owned by the 99.99th percentile is sheltered overseas. In the United States, however, the authors noticed a different, but no less striking, situation: “In the United States, offshore wealth also increases inequality,” the wrote, “but the effect is more muted than in Europe, because U.S. top wealth shares are already very high even disregarding tax havens.”

As in Scandinavia, the amount of wealth held overseas by the highest earners in other developed countries, such as France and the U.K., grew significantly over time, likely resulting in a somewhat rosier picture of wealth inequality than the reality. And, once again mirroring the team’s findings in Scandinavia, those totals could be grossly understated, Alstadsæter noted.

“Since we only include financial assets and not real assets such as art, gold, and yachts, true offshore wealth can be expected to be even higher than our estimates," she said.

According to Matthew Gardner, a senior fellow at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, the reason the U.S. exhibits such a high level of wealth inequality, even without hidden holdings taken into account, is that “we have a tax system that’s pretty much designed to help individuals accumulate wealth.”

“It’s obviously a completely legitimate system of rules, but one that’s geared toward inequality,” he said, adding that the problem could be more excusable in developing nations with less governmental and financial structure and stability. “We have the structure in place where we can monitor tax avoidance. We have no excuse.”

To combat such abuses, former President Barack Obama signed into law in 2010 the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, better known as FATCA or the “Fat Cat” tax, an additional reporting requirement for Americans with overseas assets and the financial institutions catering to them. While it passed by a 70-28 Senate vote, it’s faced a fierce repeal campaign from both lobbyists and Republican lawmakers critical of government overreach. Critics on both sides of the aisle have pointed to hypocrisy on the part of the U.S. government for requiring financial institutions in other countries to disclose its citizens’ assets while refusing to sign an international initiative similar to FATCA, called the Common Reporting Standard. The U.S., after all, featured prominently in the Panama Papers — which, as Gardner put it, might as well have been called “the Nevada Papers.”

“The U.S. has been a willing partner for a long time in the secrecy of financial assets,” he said. Until the White House and Congress enact or amend laws to boost transparency of global cash flow and increase taxes on capital gains as opposed to incomes, or “to tax wealth like work,” Gardner said, “we’re going to see continued growth in wealth inequality.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.