Trump Administration Leaked Video Shows HHS Trying To Stop Insider Leaks

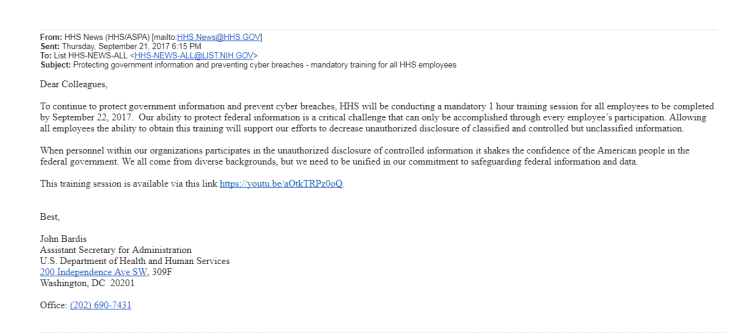

Minutes after Politico first reported that Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price had been using taxpayer money to pay for private flights — citing “people with knowledge of his travel plans” and “HHS documents” — staffers in the agency received emails directing them to partake in a training session on spotting and stopping potential leakers at work, according to emails obtained by International Business Times. The “training” consisted of a video that warned against leaks of both classified and unclassified information, included a colorfully-acted clip portraying an HHS worker who’d disseminated agency information as a depressed alcoholic and alluded to the fictional leaker’s responsibility for a fictional terrorist attack.

The training requirement may not have been a direct response to the Politico story, but it was emblematic of the vocal frustration of an administration frequently thrust into a negative light by leaks from its own staff. On Thursday, eight days after Politico’s report and amid widespread public criticism, Price resigned.

HHS did not immediately respond to IBT questions regarding the email and video.

For HHS personnel, the abrupt email appeared rather bizarre.

Having already received thorough mandatory formal entry training, HHS employees were confused by the sudden requirement that they complete the 31-minute training video, accessible via a private link, within 24 hours of receiving it — though there was no clear way of verifying that they had completed it, HHS staffers told IBT on condition of anonymity. Although the YouTube video had been viewed fewer than 46,000 times as of this writing, the department, as of 2017, had close to 80,000 full-time employees, according to its most recent budget outlay.

The 24-hour period also fell on the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah, likely rendering some employees unable to meet the deadline. Additionally, because the link to the video contained an address to “http://youtu.be,” the information technology department at the National Institutes of Health warned staff that the email was likely a phishing scam, and advised them to “report [it] as spam, ignore it or delete it.”

“Remember if it looks odd it probably is not real,” an IT specialist wrote to NIH staff the morning after the video had been sent, in an email obtained by IBT. “Why would an HHS person post training videos on youtube [sic]?”

About half an hour later, the IT specialist issued a corrective email, also obtained by IBT.

“Apparently the email from HHS News requiring training is real,” he wrote. “NIH is as mystified as we are about it.”

In the video, titled “Unauthorized Disclosure of Information Security Training” and uploaded to YouTube by the department on Sept. 20, John Bardis, the HHS’ assistant secretary for administration, asks staffers to “pause this week to reflect on how we can decrease unauthorized disclosure of classified and controlled, but unclassified information.”

Bardis refers to executive orders on management of classified and controlled, unclassified information from the administration of former President Barack Obama. He also points to the cybersecurity breach of credit card rating agency Equifax, announced on Sept. 7 and updated with news of a broader scope this week, and urged staff to consider the risk of such hacks, as well as that of “insider threats and threats from foreign adversaries.”

“When personnel within our organizations participate in the unauthorized disclosure of controlled information, it shakes the confidence of the American people in the federal government,” Bardis says in the video. “We all come from diverse backgrounds, but we need to be unified in our commitment to safeguarding federal information and data.”

In the brief role-playing clip that follows, a news anchor reports, “In regional headlines this morning, a bomb exploded in a major international shopping district yesterday. Government officials have confirmed that six Americans were among those killed in the attack. The bombing has been linked to the unauthorized disclosure of information involving U.S. activities in the region and is believed to be a retaliatory action.”

After seeing the news break on an office TV, fictional HHS staffers “Heather” and “Rich” watch as their co-worker, “Karl,” appears to be escorted from the premises by security officers.

“I just heard someone say that someone gave up our classified program, but… Karl?” Heather says, to which Rich responds, “You don’t think this is connected to the bombing, do you?”

“Oh my god, I know he’s been stressed lately, but…” Heather trails off. “If only I could’ve done something. Could I have prevented this?” The clip’s dramatic music fades, and over a freeze frame of Karl’s downcast stare slides the text “ANY GIVEN DAY.”

In a new scene introduced by the text “six months earlier,” Rich tells Karl, “We noticed you haven’t been yourself lately.” In flashbacks, Karl can be seen arguing with his wife, failing to pay bills, developing alcoholism, turning down an invitation to an after-work outing, missing a family gathering and getting passed over for a promotion — all of which the video appears to tie to his decision to leak government information.

“Our target rewards loyalty and commitment more than we do, and they pay for it,” Karl says. After Rich later alerts the Insider Threat Team, apparently averting the terrorist attack at the story’s start, Karl’s statement is described as “a reference to a dangerous adversary’s interest in our sensitive program information” in Rich’s anonymous incident report.

Next, the video features a brief tour of the Insider Threat Team, from the perspective of a new hire.

“We analyze data to mitigate potential threats,” an older staffer tells the new employee. “We see everything from unsubstantiated reports to possible espionage.” When the new hire asks him how much data members of the unit can access, he answers cryptically, “Well, quite a bit, actually, but not more than we need to do the job,” assuring her that “our civil liberties and privacy officer was a key player in getting our program up and running, and it’s an ongoing process to make sure we strike the right balance.”

Once he shows her Rich’s report on Karl’s behavior, she asks, “So, he hasn’t done anything yet?” to which the older employee responds, “No, not at this point.”

Before turning to non-fictional instructions on labeling and protecting unclassified, controlled information, among other procedural instructions, the fictional clip returns to what appears to be a version of its first scene, with the terror threat avoided. The news anchor cheerily reports, “In the Middle East, U.S. officials are attributing a decline in violence to the enhanced communication and cooperation between coalition forces and rebel factions that are holding key cities… And good news for the regional economy: A trade agreement has been approved. All parties are expressing optimism that the new effort will increase safety and stability in the region. We’ll return after these messages.” A banner below her reads “REBEL GROUPS AGREE TO NEGOTIATIONS.”

Heather observes that Karl, smiling and waving to her and Rich, yet followed closely by security guards, “seems more himself lately.”

The video ends with a few more words from Bardis, who calls disclosures of controlled information, “the greatest risk to HHS that employees can prevent.”

“When in doubt, ask your supervisor if the information you want to transfer or disclose is authorized to be disclosed in the manner you are seeking. If you are unsure, don’t do it,” he says. “So on behalf of Secretary Price and myself, thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule to watch this video.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.