Why Are Drug Prices Going Up? Democratic Power Players Help Pharmaceutical Industry In Connecticut Battle

Update at 7:17pm on 6/7: The Connecticut House passed the drug price bill intact, which now sends the legislation to Gov. Malloy for his signature or veto.

Wide majorities of voters want public officials to reduce American medicine prices, which are the highest in the world and have become a key driver of skyrocketing healthcare costs. And yet as politicians including Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have continued to call for a crackdown, corporate power players have successfully blocked even minimal reforms — with the help, at times, of industry-connected Democrats, whose party portrays itself as a consumer-defending critic of the healthcare industry.

As Congress holds more hearings on the issue, the fight over drug prices has moved to legislatures — and an intense debate in Connecticut most starkly illuminates the battle lines. There, the House, the governorship and all constitutional offices are controlled by a Democratic Party that has long criticized the pharmaceutical industry for its pricing practices. Connecticut, though, also has America’s highest number of insurance jobs per capita, and a cadre of powerful public officials with financial and familial ties to the insurance industry — a situation that adds to the influence the industry already wields through its campaign cash and lobbyists.

The clash between populist outrage at rising drug prices and the industry’s political clout in Hartford illustrates why seemingly straightforward consumer protection measures still face steep odds.

Fresh off a presidential campaign that saw both parties’ candidates promising to make prescription medicine more affordable, Connecticut lawmakers in January introduced legislation to bring more transparency to drug prices. The bill, which mirrors similar initiatives in other states, also aims to stop insurance companies from effectively forcing their policyholders to pay more for medicine than it actually costs — a lucrative scheme that critics say allows insurers and their affiliated pharmaceutical benefit managers to pocket the difference.

Despite the pharmaceutical industry’s opposition, the Connecticut legislation initially seemed headed for approval: It was sponsored by the Senate Democratic and Republican leaders and was backed by high-profile officials like the Democratic state comptroller.

But a few weeks ago, bill proponents say, Connecticut’s insurance commissioner Katharine Wade pressed for changes that would weaken the penalties in the legislation and leave enforcement of its provisions to the healthcare industry itself.

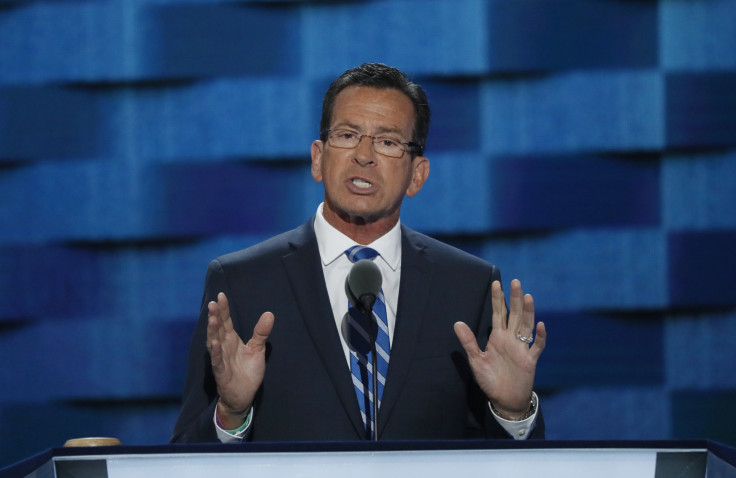

Democratic Gov. Dannel Malloy, who appointed Wade, came to her defense. “We must take much greater care in considering the impact our actions have on Connecticut insurers,” he said. House Majority Leader Matt Ritter, a Democrat, suggested lawmakers were not sufficiently listening to insurers — and then sponsored an amendment to implement Wade’s proposals. He also backed an amendment to strip out a separate provision in the bill designed to compel insurers to more explicitly disclose all their fees to policyholders.

Much of the pushback was framed as an effort to preserve the roughly 58,000 insurance industry jobs in Connecticut at a moment when Aetna is threatening to move its headquarters out of the state. However, left unmentioned was a web of familial and financial links between the Democratic officials floating changes to the bill and the industries with a potential financial interest in the legislative outcome.

- Wade is a former vice president of Cigna — the insurance behemoth that runs its own pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) and that is facing a class action lawsuit in Connecticut over its role in an alleged drug price-gouging scheme. As Wade’s department regulates Cigna and its PBM, her husband is an in-house Cigna attorney and her father-in-law, James Wade, is a partner in a law firm working for the PBM, OptumRX, named as a defendant in the Connecticut price-gouging suit. That same law firm lobbies for Cigna and for the health insurance industry’s trade association in the state.

- Ritter’s father, a former Connecticut House Speaker, runs the government relations division of Brown Rudnick — a law and lobbying firm that represents drug manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim and the Healthcare Distribution Alliance. The latter describes itself as “the national organization representing primary pharmaceutical distributors.”

- Malloy is the chairman of the Democratic Governors Association, which raised more than $6 million from donors in the health insurance and drug industries during the 2016 election cycle, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics. Malloy was reelected chairman of the group in December — and days later the DGA received $100,000 from UnitedHealth, whose PBM is a defendant in the same Connecticut class action suit over drug prices. With insurance money flowing into the DGA — which directly supported Malloy’s own election campaigns — the Democratic governor has pressed for insurance industry tax cuts, pushed state subsidies for Cigna, and blocked the creation of a publicly run health insurance option.

Katharine Wade, Malloy and Optum did not respond to IBT questions. A spokesman for Ritter said the majority leader “has not been involved in negotiating this bill or the amendments,” despite the fact the amendment, which was eventually dropped, that sought to add Wade’s language back into the bill had his name on it.

James Wade said in an emailed statement, “I have had nothing to do with this case. My appearance was filed merely to accommodate an out of district attorney to enable him to be admitted pro hac vice in this district. Other than that I have not participated in the case.”

Cigna declined to comment. Malloy and Wade have previously said that, despite their attempts to change the bill, they support the larger aims of the legislation.

That assertion has not satisfied lawmakers pushing the bill. Noting that Wade faced a state ethics probe last year over her regulatory involvement in Cigna’s proposed merger with Anthem, Democratic and Republican senate leaders criticized her work on the new prescription drug bill.

“Since you are the chief public officer charged with regulating health insurers, reviewing their financials, and approving their rates in a manner consistent with both the letter and intent of the law and the public interest, we would have expected you to support legislation that improves public transparency regarding drug prices, protects consumers from secret price gouging and prevents the off book accumulation of what is essentially premium revenue,” state Sens. Martin Looney (D) and Len Fasano (R) wrote in a May letter. “Please accept this letter as an expression of our concern regarding your attempt to influence pending legislation in which Cigna, your former employer and your husband's current employer, has a direct financial interest. We believe we have been down this path before and we fear we are heading in that direction yet again.”

“We Don’t Really Know What Happens To The Money”

America spends more on healthcare per capita than any other industrialized nation — and ever-pricier prescription drugs have fueled that trend. Spending on medicine has in recent years increased more than the overall rate of health spending — and drug expenditures now comprises roughly 17 percent of all healthcare costs, according to a recent study by Harvard University researchers Aaron Kesselheim, Jerry Avorn and Ameet Sarapatwari.

Much of the outrage about high medicine prices has been aimed at pharmaceutical manufacturers — especially after drugmakers’ headline-grabbing price spikes for EpiPens and emergency therapies to combat lead poisoning. Connecticut’s legislative fight, by contrast, spotlights the labyrinthine system of intermediaries between drug manufacturers and American consumers. In the middle of that maze of doctors offices and pharmacies are PBMs, which administer the drug benefits promised by insurers to their policyholders.

When they were first conceived in the 1960s, PBMs held out the promise of using their power to negotiate price discounts, and in recent years, three companies — OptumRX, Caremark CVS, Express Scripts — have accumulated control of the vast majority of the market. That consolidation in the $250-billion-a-year market has not coincided with lower drug prices for consumers. Instead, spending on prescription medication spiked 20 percent between 2013 and 2015, according to Harvard researchers. This year, drug prices for Americans under age 65 are expected to rise nearly 12 percent, almost five times the expected growth in wages for 2017.

In October, lawyers representing Cigna policyholders brought a class action case against the insurer, asserting that, through its deal with OptumRX, the company had illegally conspired to inflate the drug prices charged to thousands of its policyholders.

Cigna, the complaint alleged, either independently or in conjunction with a PBM, required pharmacies to jack up the prices of their prescription drugs — sometimes to more than the full price of the drug. After the patients would pay the inflated fee, usually for generic medicines, the pharmacy would funnel the difference between the drug’s original price and its newly-elevated price, also referred to as the “clawback” or “spread,” to either the insurer or the PBM, according to the suit.

The suit also alleged that the pharmacies were contractually prohibited from alerting patients of the practice or directing them to lower-priced options. In a February report, Bloomberg obtained contracts prohibiting pharmacists from publicly criticizing the PBMs or recommending less expensive ways to purchase the drugs, such as paying the pharmacy directly out of pocket.

The system, lawyers argue, is a violation of the promise that a policyholder’s payment is a shared “copay” between the consumer and the insurer — and that the consumer will never have to pay more than insurers are paying a pharmacy for the covered medication.

“PBMs can serve a helpful role in managing drug insurance, and copays can be a useful strategy when applied to expensive drugs with similarly effective lower-cost alternatives that are assigned lower copays,” Harvard’s Kesselheim told IBT. “But when copays are high and there are literally no other alternatives, then patients have a problem.”

The clawback practice is far from uncommon, according to a June 2016 survey of 640 pharmacists, conducted by the National Community Pharmacists Association. Only 16 percent of respondents said PBMs imposed clawbacks fewer than 10 times per month. More than a third said the practice occurred more than 50 times on a monthly basis, and nearly half said it happened between 10 and 50 times over the same period. A full 87 percent said the clawbacks “significantly affect their pharmacy's ability to provide patient care and remain in business.”

The survey buttressed the lawsuits’ allegations that pharmacists were prevented by “gag clause” rules from telling patients about the alleged scheme or lower-cost alternatives — even if the patient asked. Nearly a fifth of the pharmacists who participated in the study reported “gag clauses” preventing them from telling patients about cheaper options more than 50 times a month, and 39 percent said it happened between 10 and 50 times.Those cheaper options mainly included paying out of pocket — meaning patients paid more for their drugs using their insurance than if they had simply paid the cost of the drug without involving their insurance provider.

“It's really not insurance, is it?” Randal Johnson, the president and CEO of the Louisiana Independent Pharmacies Association, told New Orleans TV station Fox 8 of the alleged Cigna and UnitedHealthcare schemes. “I mean, what is that if you go in and they're negotiating a price for you, and it's actually costing you more to acquire the drug with your insurance than you could if you walked in off the street and you didn't have insurance?”

While the PBMs allegedly extracted the spreads from the pharmacies, it’s unclear whether the insurers or their PBMs are pocketing the difference between what they’re allegedly pushing the pharmacies to charge and the drugs’ wholesale prices.

“We don’t really know what happens to the money. That’s where the lack of transparency makes everything very confusing,” John Norton, the communications director of the National Community Pharmacists Association, told IBT.

“I could break into Fort Knox easier than being informed by the PBMs or insurers the portion of the clawback amount retained by either the insurers or the PBMs,” said Susan Hayes, a founder of and principal at the consulting firm Pharmacy Outcomes Specialists. But unless sponsoring companies — usually very large ones — are contracting directly with their PBMs, in which case the PBM keeps all of the clawback, the insurer and the PBM are probably splitting that spread, she said.

“Unnecessary And Antagonistic Approach Toward Connecticut’s Insurance Industry”

With polls showing that most Americans want lawmakers to move aggressively to lower drug prices, legislators have intensified their scrutiny of insurers and PBMs.

Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz., and Tammy Baldwin, D-Wisc., introduced bipartisan legislation in May to bring transparency to prescription drug pricing. But with the pharmaceutical industry’s lobbying muscle in Washington and huge campaign donations to both national parties, consumer advocates are trying to take the fight local.

“The pharmaceutical industry has spent literally $80 million lobbying in the first quarter this year. They have two lobbyists for every member of Congress in D.C.,” Ben Wakana, executive director of the newly formed Patients for Affordable Drugs, told IBT. “State capitols can provide an opening where people are a little more open-minded because they have not been bought out by pharma.”

Nearly 80 bills have been introduced in 30 states to tackle prescription drug costs, according to the National Academy For State Health Policy (NASHP). Almost all of these bills seek to bring more transparency to the pricing of pharmaceutical drugs.

In Connecticut, the legislation prohibiting both clawbacks and the “gag” contract restrictions came at a particularly sensitive time for the industry — it was introduced just as the drug-price lawsuits against Cigna and OptumRX began moving forward in the state.

During the initial hearings, consumer and physician groups argued that the bill represented an important step in shedding more light on opaque drug pricing policies.

“Pharmacists, like physicians cannot negotiate terms of their contracts with insurers,” said a coalition of medical societies in a statement to lawmakers. “Many physicians believe that if these clawbacks were outlawed and patients were given the information and allowed to choose the cheaper option they would have more disposable income for other medications and other needs.”

The pharmaceutical industry countered by arguing that the current system helps consumers.

“Any provisions that would call for manufacturers to publicly justify the price of certain therapies by detailing the input costs to develop and market them can interfere with the market-based ecosystem that works to bring down prescription drug costs through robust private-sector negotiations,” testified Patrick Plues of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a drug industry trade association.

State records do not reflect the insurers publicly lobbying on the legislation, and it is unclear how much insurers are directly receiving from clawbacks. Still, the bill’s sponsors suggested the opposition has been fueled by the industry.

“We naively assumed the health insurance industry would support these common sense reforms designed to save their policyholder's money,” Looney and Fasano wrote in May. “However, we now realize that many insurers have formed their own separate but related PBM businesses which engage in this very same practice...it is clear that the goal of insurer affiliated PBMs is to generate off book revenue that is not subject to regulatory review or public accounting.”

Among the biggest players in the legislation has been Wade, who was Cigna’s top lobbyist from 1992 to 2013. According to Looney and Fasano, Wade “proposed language that would essentially limit the enforcement of the anti-gag and anti-clawback provisions and cede that enforcement to the health insurers and PBMs themselves” — a proposal the lawmakers called the “fox guarding the hen house.”

In an interview, Looney told IBT: “I think the pharmacology groups, the manufacturers, are actually for the bill — they’ve been quite helpful. The PBMs and the insurers tend not to be as supportive. The insurers actually own some of the PBMs... I think their interests were being represented by the language the insurance department was suggesting to add to the bill.”

A spokesperson for Wade told the Hartford Courant that the senators “omitted an important part” of the language that Wade had proposed be added to the bill. Wade’s office did not respond to repeated IBT requests for comment and for the full language that Wade wanted added to the bill.

Malloy defended his insurance commissioner, saying in a statement that “to accuse the commissioner of 'interjecting' herself into an open legislative process by offering appropriate language is ridiculous on its face. It's especially ridiculous given that our administration has been consistently supportive of the underlying bill concept — to imply otherwise is disingenuous at best, and a lie-by-omission at worst."

Malloy’s statement chastised the senators for their “unnecessary and antagonistic approach toward Connecticut’s insurance industry.” The governor repeated that critique Friday, saying the senate had “turned a deaf ear on the insurance industry” when lawmakers passed a bill that would require insurers to provide additional health benefits for women, children and adolescents and expand contraception benefits.

“They are a very, very powerful lobby here in the state,” Ellen Andrews, executive director of the Connecticut Health Policy Project, told IBT about the insurance industry.

“Honestly, this is a very small thing. If a drug costs $5 why should we be overpaying? Pushback from the administration speaks to how powerful the insurance industry is here.”

“That’s A Very Important Industry To The State Of Connecticut”

Despite Malloy and Wade’s pressure, Connecticut’s senate unanimously passed the drug pricing bill — but the bill’s fate in the House remains uncertain in the waning hours of the legislative session. Ritter, the Democratic Majority Leader, along with the Democratic chairs of the Public Health and Insurance and Real Estate Committees, drafted an amendment containing nearly the exact same language that Wade sought to add into the bill. A later amendment ultimately scrapped the language.

When it comes to health insurance issues, Ritter told reporters that lawmakers should be “careful what they propose.”

“Even if it’s a concept and you want to get a public hearing, be careful. That’s a very important industry to the state of Connecticut,” Ritter said.

But while the bill could be watered down, it is also possible that time to pass it will simply run out. The session ends Wednesday, and it is unclear if the Democratic leadership will bring the bill to the floor for a vote before then, despite the bill’s unanimous passage in the Senate.

Republican Rep. Fred Camillo, a co-sponsor of the legislation, told IBT that although Connecticut politics has changed and “bills that normally would have flew through years ago are not,” he hoped the anti-clawback bill would reach the floor of the House.

“It certainly has a lot of support. We’re hoping it gets called,” he said.

Even if this bill dies, there will likely be continued pressure on Connecticut officials to combat rising drug prices, and Malloy’s administration will have the power to take — or refuse to take — such action.

Under an existing state law, Wade is empowered to revoke a PBM’s registration if it engages in “conduct of a character likely to mislead, deceive or defraud the public or the commissioner” or “unfair or deceptive business practices.”

Matthew Katz, the executive vice president and CEO of the Connecticut State Medical Society, a physicians’ group and a state-level entity of the American Medical Association, said the class action lawsuit’s allegations against Optum should “at least” warrant some sort of review by the state’s health insurance department. But he raised concerns about the familial connections of Wade, the insurance commissioner.

“The wisest thing would be for her to recuse herself if there was an ongoing investigation in this matter. If there is an investigation, she should step back, as there’d be at least a perception of a conflict of interest,” he told IBT.

“There’s a lack of transparency that could rise to the level of deception,” he said. “What seems to be happening here is the patients are getting the short end of the stick.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.