Politicians Often Play With Self-Dealing Decks, Ethics Optional

For anyone who wondered if politicians indulged in degrees of self-dealing when passing laws, a study published in the latest issue of Legislative Studies Quarterly says yes.

That shouldn’t be surprising. Previous research has shown connections between elected officials’ wealth and legislative activities. However, the picture is more complicated than a simplistic thought that all politicians are only out for themselves – no matter where in the world they are – or, even when they are, politicians are necessarily good at it.

“Legislators’ private financial holdings affect policy decisions,” wrote researchers Jordan Carr Peterson of North Carolina State University and Christian Grose of the University of Southern California in Legislative Studies Quarterly.

In three major U.S. laws passed in 1999 and 2008 that deregulated banks and bailed out the financial and auto industries, the researchers compared individual votes to multiple factors, including financial portfolios listed in mandatory personal financial disclosures.

“We found on those three that there was a statistically significant association between a legislator’s relevant investment and then their roll call [vote],” Peterson told International Business Times. The researchers accounted for other important factors, such as party affiliation, ideology, and various characteristics of the districts that elected them.

But personal financial interests contributed an estimated 5% to 8% of the decision on how to vote. That doesn’t suggest crass self-dealing, but “if it’s a close vote, that could matter a lot,” Peterson said.

Prestige and power

“It’s not illegal,” said Richard Gordon, a law professor and the director of the Financial Integrity Institute at Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio. “It might be immoral and fattening. If you trade on insider knowledge, that might be insider trading [which is the illegal use of non-public material information in investing]. But everything going on here would be public.”

Gordon pointed to some provisions of the Jobs and Tax Act of 2017 that “definitely benefited people” who had business interests in legal structures called limited liability companies.

“They love the power,” Gordon said of holding office. “They love the prestige. Some of them even have the public interest at heart. But they still get rich.”

Though, that leaves the question of whether anyone is doing something illegal or unethical. Or if they might be getting away with something.

In the last dozen years, multiple legal or media investigations have suggested that members of Congress might be making money through stock trading on inside information or the ability to influence legislation. But the stories were more inferences without hard evidence.

In 2008, as the global financial crisis was unfolding, a number of high-ranking congressional leaders, including then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell, who was Senate minority leader at the time, quickly changed their stock portfolios right after speaking with administration officials, The Seattle Times reported. All denied wrongdoing and none was charged. Millions of other Americans scrambled to save their portfolios as markets tanked, only they didn’t have the presumed benefit of chatting with administration officials.

Some in Congress were trading fast and furiously in 2008 using risky types of bets on stocks and bonds, a Wall Street Journal analysis indicated. Some made money. Others lost it, suggesting that maybe inside information isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Then there are more direct connections. Tom Price resigned as Secretary of Health and Human Services in 2017, for use of private planes. But previously he faced criticism for trading hundreds of thousands of dollars in shares of a biotech company when, as a congressman from Georgia, he was involved with legislation that affected the company, the Washington Post reported. There was speculation that Price might have violated the Stock Act of 2012 that was passed to rein in trading by members of Congress. However, no action was taken.

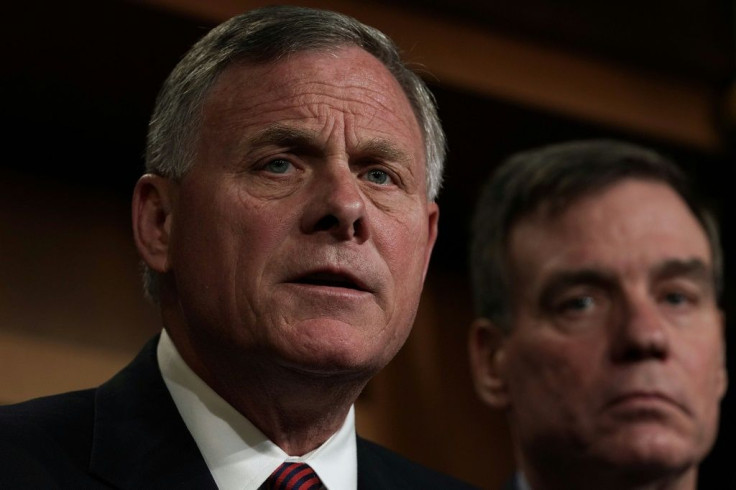

Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., resigned as chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee in May after the FBI executed a search warrant at his home, seeking evidence that he might have traded shares of stock after getting advanced briefs on the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. There have been no charges to date and Burr remains a senator.

Bad Optics

But charges or not, convictions or not, confessions or not, the optics are terrible. Such reports, even if there was no wrongdoing, still smell bad to the average person.

On the whole, people have a neutral to negative level of trust in governments globally, a report from PR firm Edelman indicates .

Some in the political sphere or who study it have a more positive view of officials.

“I think well over 90 percent get into the business of politics because they do care and want to do something for the country,” said Bruce Newman, a professor of marketing at DePaul University in Chicago. But he agrees there is certain amount of looking out for No. 1.

Jamie Miller, Florida director of political marketing firm People Who Think and former executive director of the Republican Party of Florida, says that some of what seems to be self-dealing may be more a matter of associations and pre-existing connections to people and industries.

“If you’re a medical doctor and get elected to the house, on controversial medical bills you’re going to side with the medical industry,” Miller said. “I think it’s the same thing with an environmentalist.”

“Part of it is who has access to the candidate,” Miller said of politicians who know people from previous professional connections. However, voting for a bill only because of personal gain he saw as less likely. “I have a hard time seeing someone being elected and saying I’m going to vote for this bill and make a couple of million dollars. I have lobbied professionally and have not seen that.”

But the good is mixed with the less noble.

“I always say that basically there are three reasons why people run for office: ego, power, and money,” said Dr. Louis Perron, an international political consultant based in Switzerland. Ego can mean self-gratification or greater recognition that leads to an ability to influence policy. Power is a chance to control, but also to get things done. Money can be for causes and policies – or for one’s self.

Attempts to control self-dealing can increase it.

“In Switzerland, we have this idea that we don’t want career politicians so being a member of Parliament is part time, but it is a complete illusion because most politicians are full-time politicians making money out of the office,” Perron said. “You’re sitting on the board of an insurance company or of a health insurance company, which is all 100% legal, but of course it’s corrupting the system. If you earn more with your board membership than with your political office, you’re not independent in your voting.”

Ironically, politicians who want opportunities for personal enrichment can be thwarted by their own shortcomings as investors. A 2015 study called “Capitol Losses: The Mediocre Performance of Congressional Stock Portfolios” from researchers at the London School of Economics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked at stock trading by members of Congress between 2004 and 2008. The researchers noted that members of the House and Senate didn’t seem to trade with an information advantage and, generally, the average member of Congress “would have earned higher returns in a passive index fund.”

Because, adapting an old saying, sometimes suspected crime does not pay.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.