Poverty Has Nearly Doubled Since 2000 In America

A year after Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri, people are talking about a newly galvanized civil-rights movement in the U.S. A new report, finding that the number of people living in high-poverty areas has almost doubled since 2000, suggests that its rebirth is sorely needed.

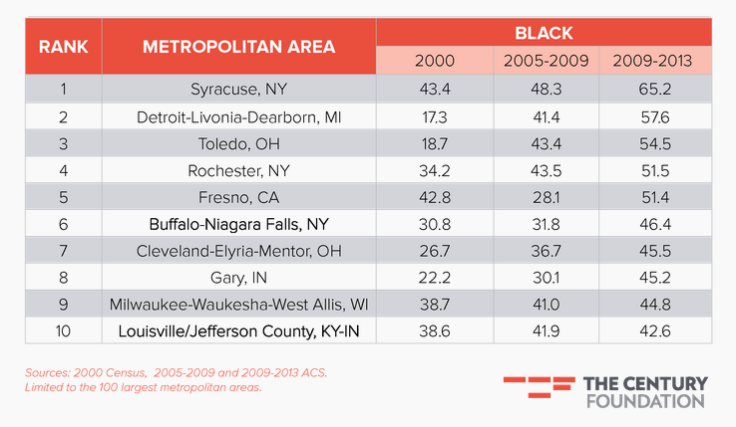

According to Century Foundation research, the number of Americans living in high-poverty areas rose to 13.8 million in 2013 from 7.2 million in 2000, with African-Americans and Latinos driving most of the gains. The report points to racially motivated policies such as exclusionary zoning and trends such as white flight as the primary culprits.

“We are witnessing a nationwide return of concentrated poverty that is racial in nature,” writes Paul A. Jargowsky, a Century Foundation fellow and the report’s author. “This expansion and continued existence of high-poverty ghettos and barrios is no accident.”

Big Trouble In Midsize Cities

Although poverty is often considered endemic in large cities or desolate rural stretches, the kind of high-density poverty described in this report is growing fastest in midsize American cities, defined as metropolitan areas that are home to between 500,000 and 1 million people. The most high-profile example is probably Detroit, where the number of high-poverty tracts more than tripled, but it is far from the worst. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, almost two-thirds of the poor black residents of New York’s Syracuse live in high-poverty areas: Between 2000 and 2013, the number of census tracts in Syracuse that qualified as high-poverty more than doubled.

This disturbing trend belies a decade of hard-fought gains in the country’s biggest cities. Los Angeles, New York, Washington and Atlanta all recorded modest declines in poverty from 2000 to 2013, a trend that Jargowsky indicates may have contributed to the lack of attention the issue has received over that period.

“Given the contrary trend in these ‘nerve center’ metropolitan areas,” Jargowsky writes, “it is perhaps not surprising the historic re-concentration of poverty since 2000 has largely escaped public attention.”

Squandered Progress

The advance in poverty charted in the report is even more disturbing when viewed alongside the decline that preceded it. During the 1990s, a sustained economic boom and a number of public-policy initiatives, comparable with the earned-income tax credit adopted years before, helped drive a 25 percent drop in national poverty levels. From 1990 to 2000, the number of Americans living in high-poverty areas -- defined by the Census Bureau as a geographic area where 40 percent or more of its residents live in poverty -- dropped to 7.2 million from 9.6 million.

Policies To Blame

Yet the gains of the 1990s did nothing to hold back two larger trends that Jargowsky identifies as the key culprits in this development: a flight to the suburbs and racist development policies. “Suburbs have grown so fast that their growth was cannibalistic,” he writes. “It came at the expense of the central city and older suburbs.”

As richer, or simply nonpoor, residents fled central cities and inner suburbs, they hollowed out the tax base that once supported programs designed to keep people out of poverty. And, as the populations outside cities grew, they used exclusionary zoning to ensure that things such as public housing were kept out of their areas, thereby confining the poor in small, increasingly poverty-stricken communities.

Using Ferguson as an example, Jargowsky points out the vast majority of the high-poverty neighborhoods in the St. Louis metropolitan area are concentrated in a small handful of communities, including East St. Louis, the City of St. Louis and Ferguson. They are surrounded by 500 suburban communities that do not have a single high-poverty neighborhood.

“It is unfortunate that well-meaning people who are reading the news and consuming the coverage of the events in Ferguson, Baltimore and elsewhere are not getting the full picture,” Jargowsky writes. “They are seeing places like Ferguson up close, but they are not seeing the larger set of forces that created Ferguson.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.