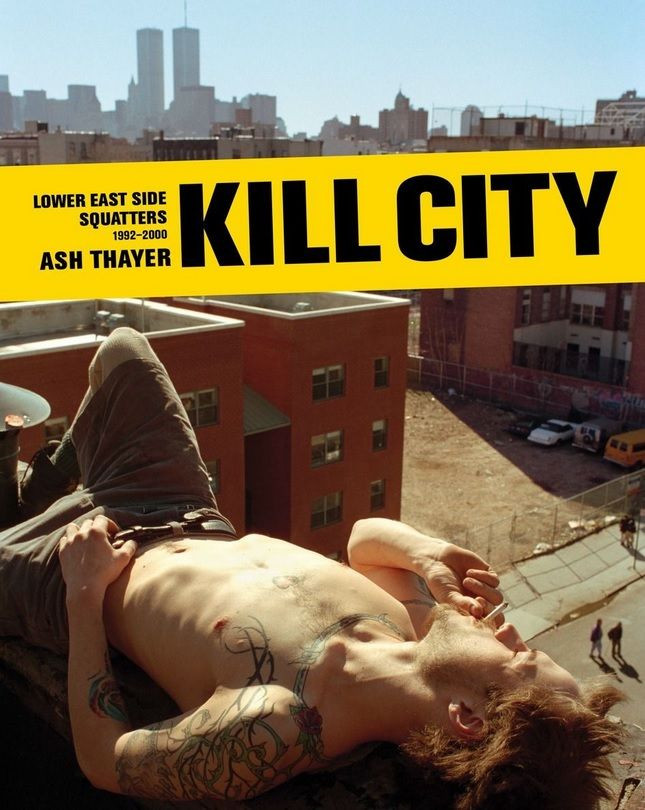

Pre-Gentrified NYC Chronicled In Photos: 'Kill City: Lower East Side Squatters 1992-2000'

New York's downtown once looked post-apocalyptic, and photographer Ash Thayer's "Kill City: Lower East Side Squatters 1992-2000" (2015, Powerhouse Books) has the photos to prove it. Back when she was in her 20s, Thayer chronicled a community she describes as a mixed bag of punks, "crusties," anarchists and train-hoppers, who arrived from all over the country to live alongside the neighborhood's famously diverse ethnic community. Even actress Rosario Dawson and her mother, who Thayer says was an activist, lived in the squats.

There, in over two-dozen "barely habitable" buildings abandoned by landlords during the 1970s, communities occupied the structures and recycled, upcycled and restored them in the hopes of getting them up to code and acquiring the titles -- something that was encouraged by Jimmy Carter's 1980s homesteading program, which was killed in the Reagan era.

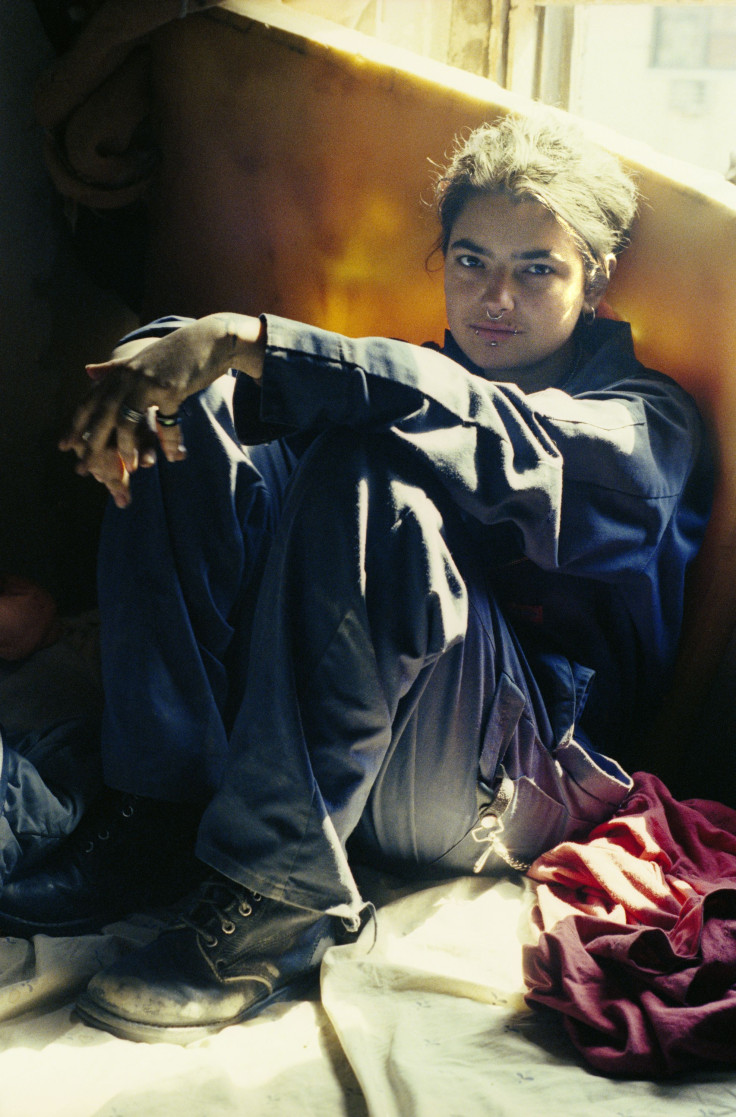

Thayer is now a professional photographer, multimedia visual artist and adjunct professor who teaches at New York University and Columbia University, but in the 1990s, she was a young art student from Memphis who arrived in New York with her Leica camera and big dreams. Unable to afford the rents, she began to live in a squat by invitation of a friend in the punk scene. "Kill City" gives us intimate access to a world most of us will never see, and rather than a voyeuristic portrait akin to the kind of "disaster porn" that inspires photographers who go to wrecked and abandoned parts of cities like Detroit, it's an insider portrait, showing beauty amid the disaster.

Thayer talked to International Business Times about what she thinks of gentrification, what it was like for a young woman to live in an abandoned building and whether "bohemia" can still exist.

International Business Times: What does the title "Kill City" mean?

Ashley Thayer: It's a song by Iggy Pop about the Lower East Side. It's an ironic play on words. At the time, Mayor Giuliani and Antonio Pagan wanted to get rid of the Tompkins Square Park homeless issue and also to get all the squatters out. It was Pagan's platform to become city councilman. The title is saying the city was trying to kill us. It's an exaggeration: It wasn’t murder, but when you evict a bunch of homeless people, it could be seen as the equivalent. Drugs and crime were rampant; the Iggy Pop song really talked about the drug issue.

IBTimes: Some people would argue that gentrification kills the heart of a neighborhood.

Thayer: The point is not against progress or cleaning up neighborhoods or creating more living spaces. It’s against the type of gentrification that is not healthy or helpful to the community that already exists. What they do by making things so incredibly unaffordable is that they price out people who are already living there by making everything around them that they have to buy -- basic life commodities -- so expensive. It destroys communities by dislocating them. It's about having longevity in a community of different ethnicities and types of people. New York City is known for the arts, and if you price all the artists out, there goes the art too. That’s one of the appealing things about the city.

The kind of gentrification I'm talking about is bad city planning. It’s bad for families, communities, and ultimately it’s bad for city commerce. You don’t have to be a socialist to have good city planning. You can still have capitalism -- although my squatter friends might disagree. There’s a balance, and it comes down to people being involved in community boards and people who say, "Yeah, we’re going to let this developer come in and do this because it’s good for the community and not just good for private interests and deep pockets."

IBTimes: What would you say to someone who says, "The neighborhood, after gentrification, is better now. It was a crack den before, with a bunch of suburban kids turned crust punks begging for change"? There are a lot of people who would have a problem with anti-gentrification arguments coming from squatters -- then or now.

Thayer: There are several different things to unpack with that argument. One myth that needs to be dispelled: White people can also be poor. Punk rock kids can be poor. A lot of kids turn to punk rock culture because it is a safe place and an outlet from cultural and social abuse. I was bullied and violently attacked from my peers for being unpopular, different, not having as much money as everyone else. I dealt with sexual harassment, violence from men. Punk rock culture became a way to band with other people who were low income, social rejects, kids who had recovered from abuse. I’m not saying all these punk kids were heroic or noble; for some people punk is a fashion show. I think you have to separate the crust-punk aesthetic from what’s going on.

IBtimes: Was the squatter scene back then synonymous with the punk scene?

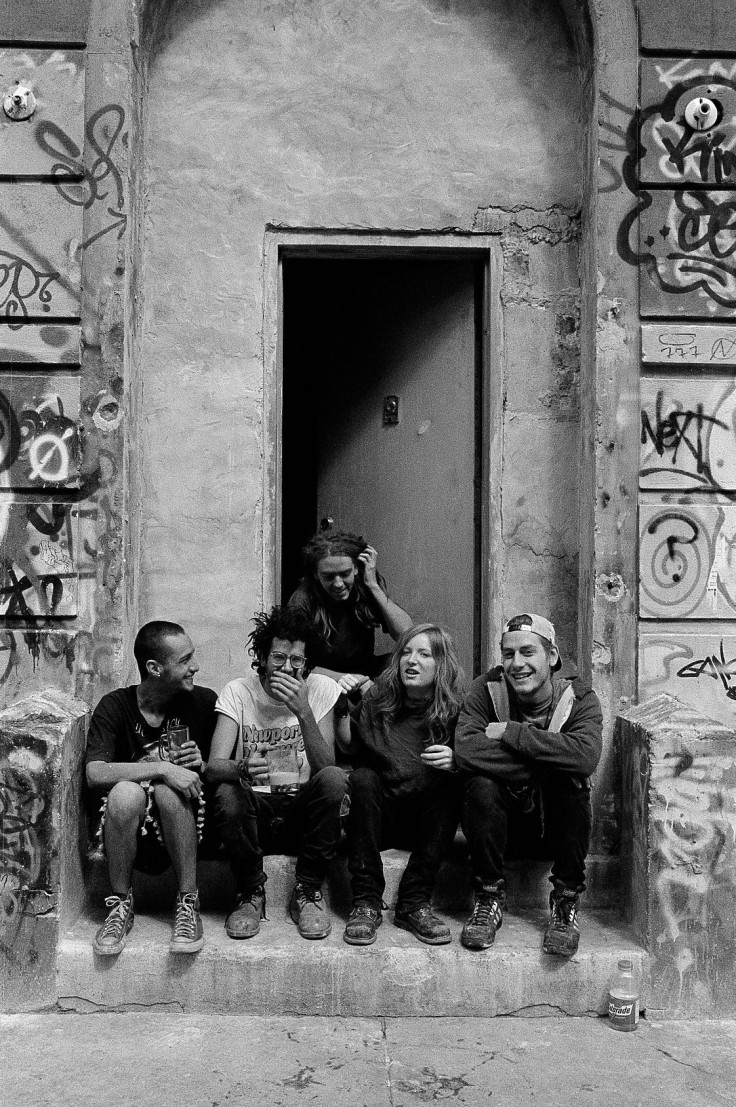

Thayer: There were different demographics of people who squatted back then. So to accredit it to one camp or demographic isn’t accurate. There were people who were locals, apolitical, families [of various ethnicities]. There were blue-collar, working-class people who needed a place to live -- maybe their landlords had abandoned them. There were people homesteading interested in bringing their buildings up to code and getting the title to them, local families who couldn’t afford high rents and needed a place to live. Then there were the idealogues or idealists who were against the sort of gentrification, capitalistic machine that was gobbling up real estate, jacking up prices.

Rosario Dawson’s mother was a squatter. Rosario grew up in the squats. She wasn’t going to punk shows -- she was probably going to school and acting classes, but her mother was an outspoken activist.

IBTimes: What do you think when you see the neighborhood now? It's pretty fancy.

Thayer: The book is a big, fat “We told you so.” Now people are like, look at how the neighborhood’s changed, and it’s sad how it’s all rich white people now. Part of the reason the Lower East Side is nicer is because squatters cleaned up the neighborhood. They made it cleaner and safer for developers and speculators to even want to go in and buy up property. That's why it was abandoned and ignored for so long, because you couldn’t get people to move in there.

IBTimes: Describe who was living in the squats.

Thayer: Most of the punks that I knew and hung out with were working really hard to create apartments and housing for themselves. There were some kids just there to party, do drugs, have a free place to stay. We called them summer campers. They’d be gone by winter because it was harsh and uncomfortable. Not every kid had a sob story.

IBTimes: Your experience is unique. What did you see as a squatter that most people won't ever see?

Thayer: Because I hung out with crusty punk kids, and because I was intimately involved in their lives, I saw their vulnerable sides. I knew their life struggles, daily challenges. I saw them scrambling for food and shelter. I saw them working really hard on apartments, trying to come up with ideas on how to build or make stuff, to gather resources, and that was incredibly moving and powerful experience. It was people with nothing or little to nothing coming up with creative and inventive ways. You have to overcome personal inhibitions to dumpster dive to get food out of the garbage and cook it. There was a lot of camaraderie around it because a lot of people would look at you and pity you. Because it’s New York City, there’s so much great food wasted. With FDA rules, people had to throw away really good food. It wasn’t half-eaten meals, it was whole sandwiches wrapped up that by law, it was the expiration date, so stores had to throw it out.

IBTimes: Yesterday’s scavenger squatter and dumpster diver is today's trendy upcycler and hipster "freegan."

Thayer: That’s what we were doing before it had a name. If you look past the cultural judgement or baggage around deciding to rehabilitate an abandoned building, it makes so much sense. With so much waste, so much excess -- and then, so much need.

IBTimes: As a woman living in essentially an abandoned building -- did you feel safe?

Thayer: I felt safer inside the squats than outside. Sometimes people were crappy, some were junkies. I never experienced any real sexual harassment. I didn’t hear about any rapes. It’s not like it was a community of thieves, where bad things were happening and people were just tolerating it. It was a lot safer than shelters. So I felt very safe, I trusted people. It was hard to get in and to earn people’s trust. And once you did, people were pretty trustworthy.

IBTimes: Your photos have a beautiful, golden glow. There's a Nan Goldin-esque feel to them. Was she an influence?

Thayer: Yeah. First of all, I love her work. It’s very tragic. I think a difference between her work and mine … a lot of her photographs have a specific tone. I wasn’t looking at sex and drug use. Her work was an exploration of that and the consquences it had on people’s lives. I was interested in the work that was happening, the phenomenon that was the lifestyle, but also about the DIY [do it yourself] culture I was a part of. I was photographing my friends in Memphis who were punk rockers. There’s a lot of hope, and people doing incredible things. The woman in the window who’s pregnant. To me, that’s one of the most incredible feminist shots that were very iconic.

IBTimes: Some people will see squalor in the photos, and some of that's there. But there are also images that are fantasies of freedom -- like the book's cover image.

Thayer: We were getting away with it. I knew that something was happening there that was really special. We were winning. It was great especially for a bunch of characters who were getting rejected and had a hard time. It was a win for us.

IBTimes: What does "bohemia" mean to you, and do you think it's important that there are still spaces for it in our culture?

Thayer: I would literally have to look up the definition of the word!

IBTimes: I guess if you lived in it, you don't have to know the definition!

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.