Precursors To Human Sperms And Eggs Created, For The First Time, With Skin Cells

British scientists have been successful in creating primitive forms of artificial sperms and eggs from human skin cells, marking an achievement that could not only transform the understanding of age- and sex-related diseases but also come as a boon for infertile couples, according to media reports. The breakthrough comes two years after scientists in Japan successfully demonstrated the technique by creating baby mice from stem cells.

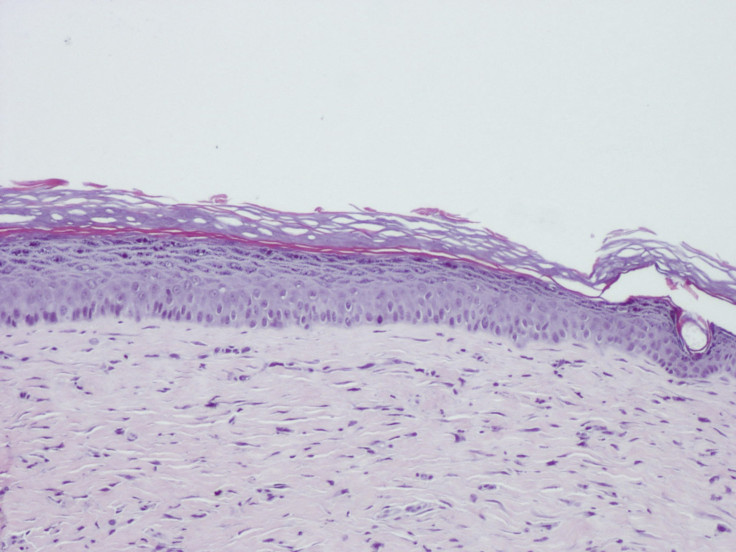

The scientists from the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge, working in collaboration with the Weizmann Institute in Israel, initially created the “primordial germ cells” normally found within testes and ovaries using human embryonic stem cells cultured in carefully controlled conditions. After initial success, the researchers reportedly replicated the procedure using adult cells extracted from human skin.

“This is the first step in demonstrating that we can make primordial germ cells without putting them into patients to verify they are genuine,” Azim Surani of the University of Cambridge, reportedly said. “It’s not impossible that we could take these cells on towards making gametes (fully developed male and female sex cells), but whether we could ever use them is another question for another time.”

Although the development of these primordial germ cells could have important implications for infertile couples looking to have kids through In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), scientists also hope to study these cells for clues to age-related diseases.

With age, people not only accumulate genetic mutations, but other changes known as epigenetic changes, which do not affect the underlying DNA sequence. These changes can be caused by smoking, exposure to certain chemicals in the environment, or diet and other lifestyle factors. The development of artificial primordial germ cells, which are stripped clean of the chemicals surrounding the DNA, could offer a better understanding of these epigenetic changes that contribute to ageing and diseases like cancer.

“It’s not just about making sperm and eggs for infertility, which would be good, but it also has implications for germ-cell tumors as well as the understanding of epigenetic reprogramming, which is quite unique,” Surani reportedly said. “This is really the foundation for future work.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.