For-Profit Colleges: Amid Investigations And Protests, Is ITT Technical Institute In Trouble?

Sandra Watson wanted to go to college, but she wasn't sure she could afford it. As she sat in the admissions office of ITT Technical Institute, an entrance counselor told her she couldn't afford not to go. Watson said that’s when the counselor began to pressure her, implying that if she didn’t sign up she’d regret it. “You’re already 27 years old,” the counselor said. “What are you waiting for?”

Watson, whose grandfather had been a police officer, enrolled in the criminal justice program, but she became concerned with its quality almost immediately. Her textbooks had typos, students were allowed to miss class with impunity and administrators repeatedly called her down to the financial aid department to sign loan agreements with climbing totals.

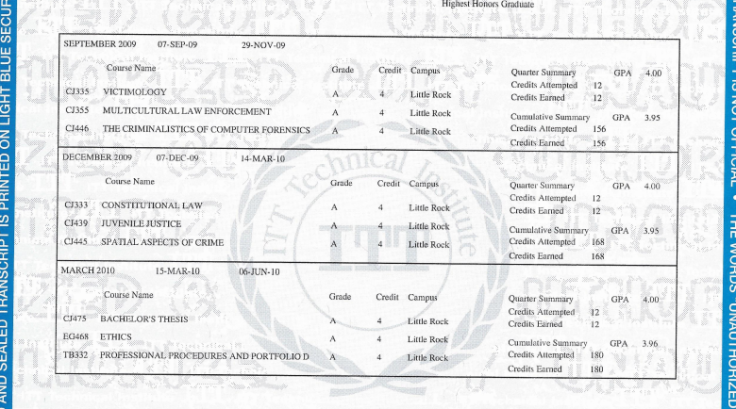

Watson asked to transfer, but she learned no local colleges would take her ITT course credits. Already halfway through the program, she resolved to finish. Watson threw herself into school, simultaneously working a full-time job and sometimes sleeping only three hours a night. By commencement, she had a 3.96 grade-point average.

Even so, she said she couldn’t land a job in her field. Watson knew how hard she’d worked for her degree, but that didn’t matter to interviewers. “Once they saw my transcripts from ITT Tech, they either told me I wasn't eligible or I never heard from them again,” she said.

A decade later, living in Sebastian, Florida, and selling jewelry on Etsy to help her husband with the bills, 37-year-old Watson starts to cry when she talks about her college experience. Watson has 16 student loans, owing a total of $93,500 for a degree worth nothing to her.

“It’s as if the school has ruined everything,” she said. “No one wants me.”

ITT Educational Services Inc., a publicly traded company with more than 45,000 students at some 140 campuses in about 40 states, runs one of the largest for-profit college chains in the United States. But that may soon change. ITT is facing investigations by multiple government agencies and complaints from graduates like Watson, who allege recruiters deluded them about the prices they’d pay for school and jobs they’d land afterward. Meanwhile, enrollment and revenue are slipping.

ITT Technical Institute’s downslide has inspired comparisons to Corinthian Colleges Inc., which shut down in April after years of fighting regulations and forced the White House to initiate a debt relief scheme that could cost up to $3.5 billion and cover 350,000 disgruntled alumni. Now, as the controversies pile up and former students organize massive protests against the company, experts say it’s possible that ITT could be the next for-profit college chain to collapse. If that happens, thousands of students might have to start over and the government could be saddled with the burden of forgiving millions in student loans.

“If the school is really systematically leaving students worse off than if they hadn’t gone to college at the institution, then they shouldn’t be operating,” said Elizabeth Baylor, the director of postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress, a progressive policy institute based in Washington, D.C. “But then, nobody wants to be cheering for students to lose their school … we also have to have clear safeguards for students.”

When contacted by International Business Times requesting an interview with an executive, ITT spokeswoman Nicole Elam sent emailed answers to questions. She wrote that the company remains confident about its future, operations and service to students. Elam said ITT is in a “materially different financial condition” than Corinthian was.

“The two situations are virtually incomparable,” she said, adding, "We remain focused on our students and their best interests and expect to continue to do so for a long time."

For-Profit Colleges 101

The nation’s roughly 3,400 for-profit colleges can derive up to 90 percent of their revenue from federal student aid programs, which include loans, grants and work-study money under Title IV of the Higher Education Act. In 2011, taxpayer support to for-profit colleges totaled about $32 billion. Corinthian, for example, was reportedly getting about $1.4 billion annually before it shut down. ITT received about $797 million in Title IV funding between 2013 and 2014.

Whereas traditional nonprofit colleges run by states or trustees allocate revenue back into the schools, for-profit colleges owned by shareholders are allowed to divide up revenue among themselves, according to a 2014 report from the Center for American Progress. As a result, some for-profits have developed negative reputations for methods aimed at boosting revenue. For example, chains often advertise students’ job prospects. But in at least one study, employers have rated for-profit college graduates among their least-desirable job candidates, possibly due to the industry’s reputation for having lower admission and graduation standards.

The Obama administration has pursued new rules aimed at protecting people from these allegedly predatory practices. In one case, the White House enacted gainful employment rules that require for-profit and certificate programs to prove their students are making enough money after graduation to comfortably make regular loan payments or face losing aid.

"I think it's appropriate for the government to demand accountability," said David Halperin, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who tracks investigations into for-profits. “The complex and expensive process of paying back students who were ripped off should force the government to realize that it’s time to stop making the problem even worse by sending money to schools that are just as bad as Corinthian."

Corinthian's shutdown was years in the making, following allegations it rigged job placement rates, spread false advertising and issued predatory loans to students. The chain paid $6.5 million to settle a 2007 lawsuit over claims it gave students inaccurate salary and employment information, and in 2014 the Education Department ordered it to shut down 12 campuses and sell the other 85. The Zenith Education Group bought most of them in February 2015, but as the department continued to levy fines on Corinthian the corporation found itself unable to find a buyer for the remaining colleges. It closed the rest of its properties in April, leaving some 16,000 students in the lurch.

The Education Department vowed to help students who felt defrauded by Corinthian, but it lacked the infrastructure to handle the influx of requests. As a result, critics attacked its handling of the shutdown, alleging the department made it too difficult for students to get their money back. More than six months later, federal education officials are still working on a streamlined process to relieve debt and hold schools accountable — perhaps in preparation for the next for-profit college collapse.

“Sadly, we think this will not be the last domino to fall,” outgoing Education Secretary Arne Duncan told reporters in June. “And we're looking at this with an eye first to doing the right thing by the Corinthian students. But we're also … trying to send a very clear message to this industry.”

The tough talk has educators closely following interactions between the White House and for-profits to determine which chain could be the next to shut down, leaving thousands of students without degrees. The industry’s instability has caused several changes for its major players in recent months. There’s the University of Phoenix, whose parent company saw stock fall 32 percent in one day in October. There’s the Education Management Corporation, which closed 15 of its Art Institute campuses in May. And then there’s ITT.

Predatory Practices?

ITT is owned by ITT Educational Services Inc., which has its headquarters in Carmel, Indiana. It was founded in 1946 and was a subsidiary of the ITT Corporation from the ’60s until its initial public offering in 1994. Starwood Hotels and Resorts Worldwide Inc. merged with ITT Corporation in 1998, and the ITT Corporation lost its beneficial ownership a year later. ITT/ESI uses the “ITT” name under license.

Like other for-profits, ITT focuses much of its efforts — and its budget — on recruitment. A 2012 report commissioned by recently retired Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, discovered that ITT allocated nearly a fifth of its revenue to marketing.

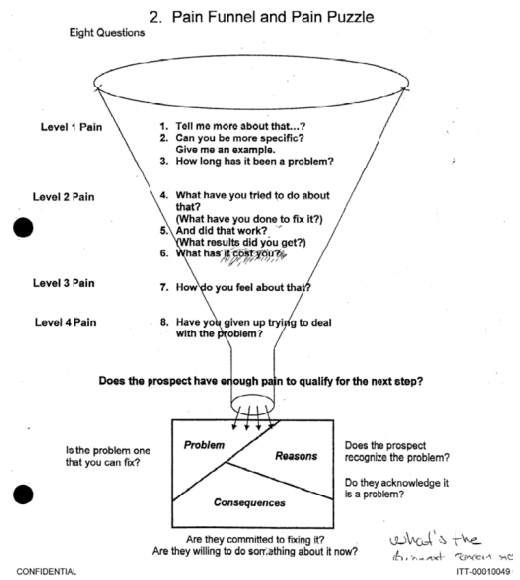

Harkin’s report listed various ways school recruiters persuaded prospective students to sign up. They were persistent — “recruiters are instructed that they are to make 140 calls a day if they have no appointments, and 100 if they have one,” the report read. They were bribed — managers could give out prizes, awards and better shifts to successful employees. They were calculated — “recruiters are instructed to ‘poke the pain a bit’ and remind them what things will be like if they don’t continue forward and earn their degrees,” the report read.

Dawn Lueck, who said she worked for both ITT and Corinthian, described admissions as a streamlined, regimented process. The 34-year-old said she attended weekly meetings where potential applicants were discussed in detail.

“You’re drilled so much on these students you start getting disconnected from the students’ actual story and what happened in their lives because all that information is brought into meetings to strategize on how to get them into class,” Lueck said. “‘Were they vulnerable? Where was their support system? Tell me about your early education. Who knows that they’re meeting with me today that really cares?’ You’re asking questions that really should establish trust. But you’re using it.”

Lueck started working at the ITT campus in Henderson, Nevada, in 1999, and moved to the company headquarters in 2002. She was a refund coordinator for a year, then returned to a campus in Murray, Utah, where she served as a financial aid administrator, recruitment representative and eventual director of finance. In 2007, she transferred to a campus in Phoenix. She joined Corinthian in 2009 but later left the business because, she said, “I just reached a point where I’m selling my soul, and it doesn’t feel good.”

During her time with ITT, Lueck became a master at her craft: getting students to enroll in, and stay in, class. She learned how to get students to come back within 72 hours of initially expressing interest — a window where they’re emotionally unstable or “still hot,” she said. The financial aid process was vague and confusing. Lueck said she and her colleagues were taught to only show potential students nine months of financial statements at a time. Sometimes, they rushed applicants on purpose.

“You’re throwing these amounts of dollars out in front of them, assuring them that they’re going to get the job to pay this back,” she said. “When you’re in an appointment for 45 minutes and you’ve got 18 pieces of paper flooding in front of you, then it’s online … how many students were clicking not knowing they were clicking to sign and authorize a master promissory note?”

Lueck recalled using return on investment graphs designed to show students how much they stood to make based on the program they pursued. But that research was funded and presented by ITT itself, so how true could it be? she said.

“ITT Tech is so good at arguing that ‘No, they’re not doing anything wrong’ because they know their process so well,” she said. “I lose sleep at night about this: These people really showed up with this dream. They believed this is going to better my life, and it is not what’s happening.”

Shielding Students, Or Trying to

Christina Hammond, a 35-year-old ITT alumna in Grand Rapids, Michigan, wears a black-and-white striped prison uniform whenever she visits campus these days. She stands on the side of the road, near the line of picket signs warning would-be students to turn back and hands out fliers printed with facts about the school. A duct-taped ball and chain sit in the grass around her ankles.

Hammond knows she looks crazy — she wants to draw attention. But the inmate identity doesn't appear to be much of a stretch.

Hammond, who graduated in 2013, describes her ITT experience as a nightmare she can’t wake up from. She developed depression when she couldn’t find a job in her field. She and her husband stopped talking about having children because of the overwhelming debt. Just last month, a grandmother removed Hammond from her will because she was afraid collectors would prey on the inheritance.

“A person with a life sentence from prison, it doesn’t matter what they do to try to get out — they’re going to serve their time,” said Hammond, who owes $104,000 in student loans. “I feel like that.”

The government has stepped up its scrutiny of ITT in recent years. In February 2014, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau sued the company for predatory student lending, alleging that it pushed many students into private student loans “destined to default.” It said ITT relied on the fact that its credits weren’t transferable to trap students and also misled them about their job prospects. Annual tuition at ITT costs roughly $26,000.

About a year later, the Securities and Exchange Commission accused the company and its executives of defrauding investors by hiding the poor performance of two private loan programs. The programs gave students off-balance sheet loans, and ITT convinced financiers to buy in by promising them guarantee payments if too many students defaulted. But when the loan pools performed badly, the company allegedly didn’t tell investors it faced paying millions in guarantees. It found ways around it, like secretly making payments on delinquent loans itself to keep them from defaulting, according to an SEC news release .

This past September, the U.S. Department of Justice announced an investigation into whether ITT purposefully provided false statements and defrauded the government. In October, the Education Department imposed tighter reporting requirements in order for ITT to keep getting federal aid. Under the new rules, the chain has to make sure that a student attends enough courses before it disburses financial aid to them and submit a monthly enrollment roster that includes disbursement information.

Essentially, ITT students were enrolling and withdrawing from classes so fast that the school couldn’t keep track of its money, said Baylor, the director of postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress. These and other developments might not bode well for ITT’s future, she said.

“All of these things sort of indicate a record of bad practices,” Baylor said.

But the Education Department might be poised to better handle an ITT shutdown simply because it already experienced Corinthian’s. In April, authorities found themselves so overwhelmed that they jump-started a change in borrower repayment schemes, later hiring Special Master Joseph Smith to develop a debt relief system for defrauded students. Similarly, lawmakers were inspired to call for protections that would make for-profits have proverbial skin in the game. The rationale behind this is that if the schools shut down and leave students stranded, taxpayers won’t have to shoulder most of the debt. The specific measures could come in the Higher Education Act, which is up for reauthorization this year.

A Teacher’s Anguish

On the first day of classes, former ITT computer networking professor Deanna Hennigar used to pull certain students aside, close the door and offer them an out. She’d say she knew they couldn’t afford the school, so if they wanted, she would mark them absent. That way they could drop the class and not have to pay a full semester’s worth of fees.

“The amount of money they charged these people was not fair at all,” Hennigar said. But “I don’t think I ever had anybody drop out. I was really good at bringing them in and keeping them. I kind of feel guilty about that — not about the education they got. The way they got taken monetarily.”

Hennigar, 60, loved her students, and they loved her back. She entered classrooms to calls of “hey, Miss H!” She came in early and stayed late, conducting impromptu advising sessions at her desk. She said she was voted “teacher of the quarter” at the Austin, Texas, campus in 2008 and held the title for four years.

Even today, she stands by the education her students received. She said the curriculum she taught was solid and well-paced. Career counselors held mock interviews to prep people for job hunting, and Hennigar said the students who worked hard generally got hired after graduation by companies like Cisco or Dell.

Meanwhile, the school’s administrative side was changing. In her later years, Hennigar said counselors often pigeonholed people into programs they didn’t request — it was “about the numbers, not about the students,” she added. ITT switched up its schedule so classes ran longer every night, which Hennigar said made attending school harder for adult learners who worked all day. Administrators asked Hennigar to lead classes outside her field, causing her to spend 60 hours a week working. She ended up teaching courses in paralegal writing, computer studies, structured cabling, sociology and business.

Hennigar said she was eventually fired for letting students leave early on the last day of classes. Now, her LinkedIn and Facebook feeds are filled with former students complaining about student loans.

“When I left, I felt abused,” she said. And she wasn’t the only victim: “I felt very badly for the students who went there. They will never be able to pay that money back.”

Money, Money, Money

ITT’s revenue in 2014 was about $962 million — down about 10 percent from the year before, according to its annual report on Form 10-K. As of Sept. 30, 2015, ITT’s total assets were $728 million. The corporation’s third-quarter earnings report shows it spent $20.1 million on settlements and legal fees in the first nine months of the year.

Elam, the chain's spokeswoman, said in a statement that ITT is complying with the Education Department’s requirements and being cooperative in all investigations -- many of which the company has publicly criticized. For example, after the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announcement, ITT released a statement saying the complaint over predatory student lending shouldn’t have been filed for a variety of reasons, one of which was that the issues didn’t fall under its purview. A federal judge later granted ITT’s motion to dismiss one of the four counts.

ITT denied any wrongdoing in a statement about the Securities and Exchange Commission charges, as well, saying it “repeatedly expanded [its] disclosures in an effort to present material information to investors.” As for the Justice Department probe, it simply said its compensation practices were in compliance.

Elam said ITT hasn’t received any “out of the ordinary” student or investor reactions to recent news, but she noted fluctuations in enrollment. At the end of 2012, ITT had about 61,000 students. This past September, it was down to 48,000. She added that more than 70 percent of ITT’s class of 2014 got jobs using skills taught in their degree programs.

But on a conference call last month, CEO Kevin Modany told listeners he was “certainly not pleased” with the company’s declining new student enrollment numbers. He announced a plan to reverse the trend by customizing communications for individual students and helping them make informed decisions.

Kevin Kinser, an associate professor and for-profit college expert at the University at Albany, also noted that the restrictions the White House put on ITT were more relaxed than those for Corinthian. He suggested the government may be hesitant to take ITT down because it’s still scrambling to figure out how to forgive Corinthian students’ loans.

“The department is concerned that if they hit ITT too hard, they will have a Corinthian times three on their hands with trying to deal with the blowback from it,” Kinser added. “The department is now very aware that its regulatory action could be catastrophic to an institution.”

‘The School Has Ruined Everything’

ITT’s TV commercials were what drove Watson, the criminal justice graduate, to initially visit the Little Rock campus shortly after moving there in 2005. The advertisements made big promises: night classes, small groups and hands-on activities. Plus, there was the lure of employment.

The day she graduated, Watson was optimistic. She wore a thin black robe as she crossed the stage in a dark auditorium, celebrated with an Outback Steakhouse dinner afterward and felt pride swell in her chest at being the first in her family to go to college. The daughter of a 10th-grade dropout and a longtime Kmart employee, Watson was determined to forge a career in criminal justice with her newly minted degree.

Over time, Watson’s warm memories have grown cold. She’s watched her inbox fill with job rejection letters, seen her house go into foreclosure and started screening phone calls to avoid collectors. She said she’s angry not only at ITT for defrauding her but also at the government for not fighting back.

“It’s been one of those things where I thought I was going to be bettering myself by going to that school, because they make it sound so great in the beginning,” Watson said. “And just slowly, as it went on, it got worse and worse.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.