Proposed: Apollo Lunar Landing Sites National Historic Park On The Moon

The U.S. is home to the Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, but despite its name, the park lies in a remote corner of Idaho. Now, two Democratic politicians are pushing for a national park that doesn’t just resemble the moon; they want one that’s actually on it.

Introducing the Apollo Lunar Landing Sites National Historic Park on the Moon, a destination that would require an oxygen tank and a 239,000-mile journey to visit, it could join Civil War battlefields and presidential estates on America’s roster of federally protected preserves.

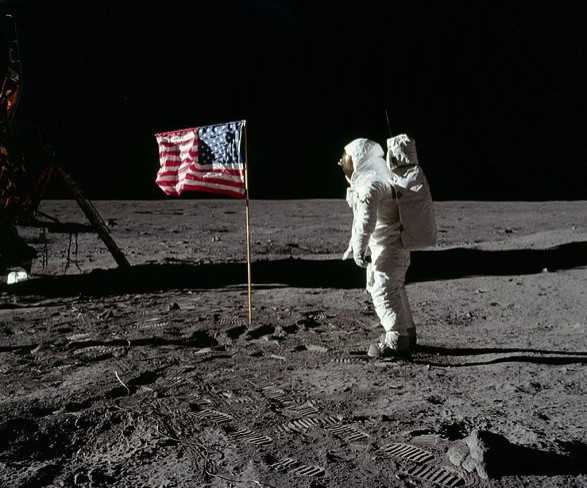

Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.), the top-ranking Democrat on the House Space Subcommittee, proposed legislation on Tuesday, along with Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-Tex), to establish the National Historical Park on the moon under the Apollo Lunar Landing Legacy Act. The designation would protect the site where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin first touched down on the lunar surface in July 1969.

“As commercial enterprises and foreign nations acquire the ability to land on the moon, it is necessary to protect the Apollo lunar landing sites for posterity,” the proposal noted. “Establishing the Historical Park under this Act will expand and enhance the protection and preservation of the Apollo lunar landing sites and provide for greater recognition and public understanding of this singular achievement in American history.”

The proposal is largely seen as a reaction to a 2011 NASA report on the potential impacts of commercial lunar visits. NASA said several commercial companies had been in contact, seeking guidance on how to approach the “space assets.”

The park, if approved, would be established no later than one year after the date of enactment as a unit of the National Park Service, which, thus far, only stretches beyond North American borders to include preserves on U.S. territories (and is already having trouble keeping its earthly possessions open to terrestrial visitors). The moon park would then be submitted to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, for possible designation as a World Heritage Site.

The Department of the Interior and NASA would be jointly in charge of protecting the artifacts remaining on the surface of the moon from the Apollo 11 through Apollo 17 missions, which ended in 1973, while the Smithsonian Institute would help ensure an accurate cataloging of the items, which include flags, a memorial to fallen astronauts, lunar landers, a golf ball and a moon car.

Under the Apollo Lunar Landing Legacy Act, the Secretary of the Interior could accept donations from, and enter into cooperative agreements with, foreign governments and international bodies, organizations, or individuals to further the purpose of an interagency agreement or to “provide visitor services and administrative facilities within reasonable proximity to the Historic Park.”

The bill specifies that only the artifacts (U.S. government property), not the land itself, would be included in the park. Yet, whether or not the moon proposal is even legal under international law is in question.

The U.S. is party to a 1967 United Nations Outer Space Treaty that states: “Outer space is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

The treaty, joined by the Russian Federation and 100 other countries, also states that space artifacts are property of the nation that launched them, making elements of the proposed park somewhat redundant.

GovTrak.us, which tracks congressional proposals, estimates that the legislation won’t even make it off the ground. It says H.R. 2617 has a 21 percent chance of moving past committee and just a 7 percent chance of being enacted.

The Democrats may be asking for the moon too soon. As space tourism kicks into full gear in coming years, however, the idea of space rangers and the protection of space artifacts might not be so otherworldly.

After all, if commercial space tourism companies have their way, these sites could become bucket-list items for thrill-seeking multimillionaires by the end of the decade. Who has the jurisdiction to protect them, however, is another question entirely.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.