Protests In Tahrir Square And Subsequent Higher Oil Prices Due To Fears Of Oil Disruptions Are Bolstering Pipeline Activity In The Heart Of The US

With about 7,000 miles between Cairo’s Tahrir Square and Oklahoma, residents of the town of Cushing are less likely to be following the Egyptian protests than they are whether the bass are biting out at the lake that gave the hamlet its name.

Yet some think they have found a connection between the current epicenter of the Arab Spring and the small, remote town of about 7,800 that has the distinction of being the busiest pipeline hub for domestic crude oil in the U.S.

The present dramatic rise in crude-oil prices worldwide, which led to a 23 percent spike in the price of crude produced in the U.S. Midwest between mid-April and early July, to $106 from $86, can be directly attributed to those disaffected Egyptians amassing in and around Tahrir Square, said Christopher R. Knittel, an energy economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management.

Unrest in the Arab world generally, and in Egypt particularly, has instilled fear in traders and other market participants that shipping through the Suez Canal, which serves as a conduit for 4 million barrels of oil every day, could be disrupted, Knittel said. “Egypt made some players in the market very uneasy as to what might happen in the near future with supplies,” he said.

A world away from Cairo -- geographically and culturally, at least, if not economically -- Cushing’s Joe Naifeh was skeptical of that idea. “You know, I don’t think it has to do with Egypt at all, I really don’t,” said Naifeh, owner of Naifeh’s Deli and Grill, where the Friday special was Frito chili pie. “As far as a direct cause of what’s going on here in Cushing, Oklahoma, and in the United States as far as oil production, it’s not hurting matters, but it’s not the cause of it.”

In effect, Naifeh and Knittel are both on to something. It is true that increased flow of oil through Cushing involves more than concerns about the Suez Canal. Also in play is vastly expanded infrastructure in the U.S., which enables domestic sources to better respond to shifts in global markets. But experts who spoke with the International Business Times attribute most of the global volume and price changes to uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East.

U.S. oil producers “are seeing an opportunity to get the economic [gain] from the political uncertainty” not only in Egypt but also in Syria, Libya and Algeria, said Charles K. Ebinger, director of the Energy Security Initiative at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

The price of U.S. crude -- the benchmark long called West Texas intermediate, or WTI (INDEXDJX:DJUBSCL) -- is heavily influenced by the price of its European counterpart, a crude known as Brent blend, which is the pricing standard for two-thirds of the world’s traded crude. When Brent prices rose over worries about the Suez Canal, the price of WTI went up as well, Knittel said. “Anytime there is a price increase that drives up the Brent price, that is going to affect the U.S. [price],” he said. As Brent prices go up, oil producers in the U.S. Midwest and in Canada have more incentive to sell their oil to Europe, which further drives up WTI prices, Knittel said.

The other major reasons U.S. crude oil prices have soared during the last three months are the expansion of pipelines in the heart of the Midwest, in response to increasing amounts of oil available in North America due to the shale boom and spare Canadian products. Until recently, the U.S. had limited pipeline capacity to transfer the abundance of oil that is stockpiled in Cushing. With new pipelines coming on-line, that glut can begin to be released to take advantage of high prices elsewhere.

Here is a chart showing the increase in the ending stocks of crude oil (in thousands of barrels) at Cushing from 2004 to 2012:

“The longer-run story really is this infrastructure issue,” said Hillard Huntington, executive director of Stanford University’s Energy Modeling Forum. “We are now in a market which we are slowly chipping away at this difference between the U.S prices [WTI] and prices on the world market [Brent].”

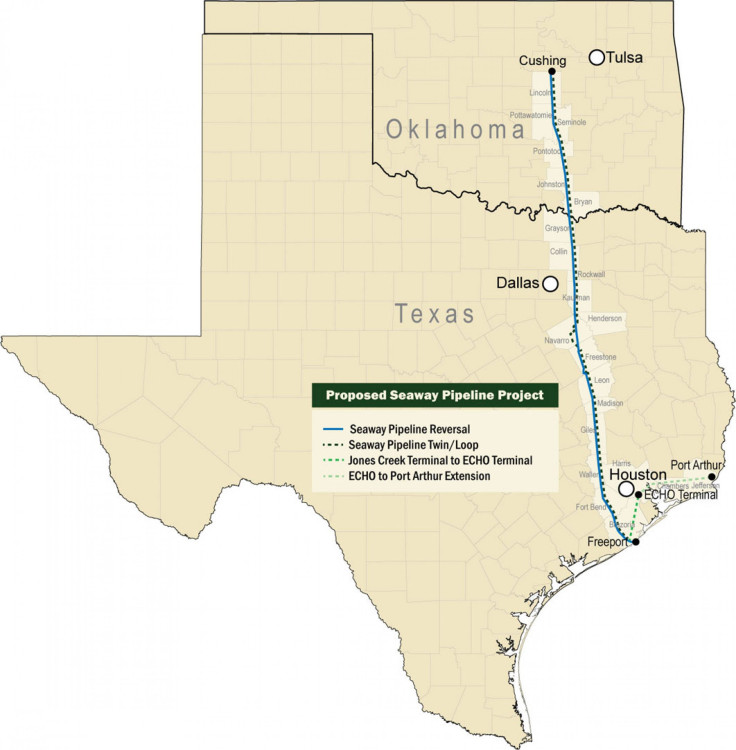

Until recent years, U.S. crude stored in Cushing was shipped north and east, but as more oil was produced in the upper Midwest and in Canada, refineries in the eastern and northern U.S., as well as in Canada, have not been able to keep up with the glut. That created the need for more pipelines to the Gulf Coast, which has led to new construction along the Seaway pipeline between Cushing and Freeport, Texas (which has already started moving crude), as well as the Keystone Gulf Coast pipeline. With greater access comes greater ability to respond to rising prices, such as those occurring worldwide now. In turn, that will create more incentive for expanding access.

The first Seaway pipeline came on-line in June of last year and initially moved 150,000 barrels of oil per day from Cushing to refineries in Texas. In its second phase, completed in January of this year, the capacity increased to 400,000 barrels per day: However, there are no current figures for the number of barrels of oil per day being moved now, a Seaway representative told the IBTimes. Another Seaway pipeline running parallel to the existing pipeline is being built now and will become operational in the first half of next year. Called the Seaway Loop, it will have a capacity of 450,000 barrels of oil per day.

The other major pipeline, Keystone Gulf Coast, is being built by the TransCanada Corp. (NYSE:TRP), the company that proposes to build the controversial Keystone XL pipeline awaiting Obama administration approval. A TransCanada representative said the Gulf Coast pipeline, which is 80 percent complete, will extend from Cushing and carry 700,000 barrels of oil per day to Texas refiners by the end of the year.

Now “there is more ability, more capacity, [and] having a pipeline out to the Gulf Coast allows you to sell to a market you couldn’t sell to before ... It is like having an increase in demand for your product,” Stanford University’s Huntington said. As a result, U.S. oil inventories in Cushing are at a seven-month low of 367 million barrels.

The question, then, is why releasing a glut of oil in Cushing doesn’t lead to falling prices, owing to the economics of supply and demand. The answer, MIT’s Knittel said, is that WTI prices go up in response to worldwide demand, and the volume of oil from Cushing is not significant enough to influence global oil prices directly. Likewise, higher prices for WTI do not automatically translate to higher gas prices at the pump, which are more directly influenced by world oil prices.

Currently, the price of WTI is actually higher than that of Brent: This month, for the first time in three years, the price differential between the two all but disappeared. Brent crude closed at 106.68 and WTI crude closed at 108.02 Friday.

And, for now, domestic oil companies are to some degree profiting from the unrest in the Middle East and North Africa. “The oil actually never has to go from the Midwest to Europe for Europe prices to impact U.S. prices,” Knittel said. “Just the threat of me [the U.S.] being able to send it to Europe will drive up my price.”

Added the Brookings Institution’s Ebinger: “The uncertain geopolitical situation is not just Egypt ... there is still very great concern of the Syrian conflict that will increase a Shiite-Sunni war and spread far beyond Syria’s border. Potentially disrupting and creating political problems in Saudi Arabia ... if it gets out of hand it can disrupt a lot of oil supplies.”

Asked if there is a clear correlation between that instability and oil profits in the U.S., Ebinger replied: “Oh, absolutely. This is not new -- different people always take advantage when they can get more dollars for a barrel.”

Finally, in other news, the Cushing Lake fishing report indicated largemouth bass fishing is pretty slow due to high surface water temperatures of around 82 degrees Fahrenheit.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.