Yik Yak's Baltimore: No Campus Is An Island

Much media attention has been paid to social media accounts of the Freddie Gray demonstrations, and the violent turn that some of them took. Twitter reaction roundups proliferate, and even the fledgling Periscope has played a role in media coverage of the events in Baltimore.

But there is another social network that has been largely overlooked: Yik Yak. The anonymous, student-centered app has become so ubiquitous that rival app Secret is shutting down. Far more than a welcome distraction during finals week, the app provides a powerful portrait of two Baltimores.

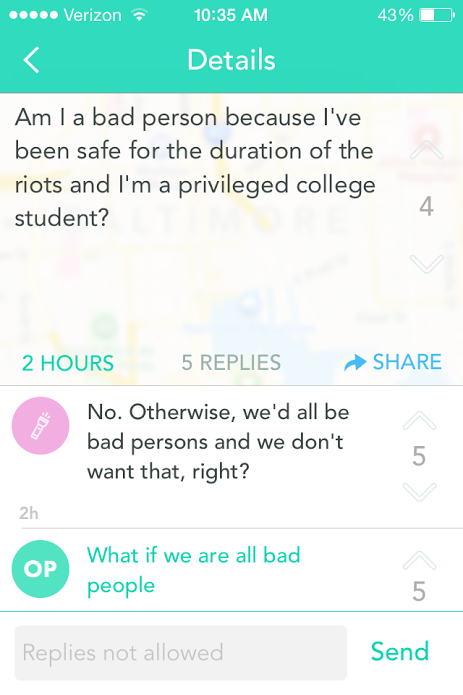

Am I A Bad Person?

Johns Hopkins University is a highly competitive school. Only 12 percent of undergraduate applicants were admitted to the class of 2019. Despite the fact that the class of 2019 is JHU’s “most diverse yet,” less than a third of the class identifies as underrepresented minorities in a city that is 63.3 percent black.

JHU also is the third-largest employer in Maryland -- so demographic mismatch aside, the campus and the local community are inextricably linked. But Yik Yak posts from this week reveal that the student population isn’t exactly comfortable with that overlap.

JHU is not the only elite university in the United States surrounded by an underserved community -- Yale, Duke and the University of Pennsylvania also come to mind. However, in the wake of demonstrations that captured the attention of the world, the school is uniquely situated for self-reflection.

“Part of being a privileged student is you can turn away from the world whenever you want,” says Mariam Banahi, a doctoral student at JHU. Meanwhile, Gray’s death and the frustrations that poured out in its aftermath are no surprise to students of color: “We carry our vulnerabilities every day.”

The Meaning Of 'Nonaffiliates'

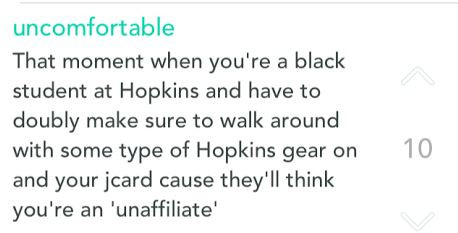

“Black people on campus don’t feel anonymous,” says Madeline Streiff, who graduated from JHU early, in December 2014. She references campus security alerts, which refer to nonstudents as "nonaffiliates" -- a term many in the campus community have come to see as a euphemism for “black”.

When these alerts go out there is a sense of, " 'Why don't you just say black because we know what you mean,' " Streiff says.

The above post calls to mind the refrain of Martese Johnson, a black University of Virginia student bloodied by police as he repeatedly asserted “I go to UVa!”

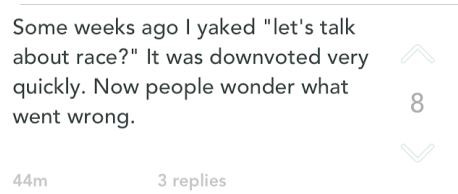

At the same time black students feel hypervisible, they also feel like issues of race are invisible. Or, in the language of Yik Yak, downvoted:

On Yik Yak, students seem a lot more comfortable making anonymous jokes about their own privilege than facing it head-on. According to Kidist Ketema, a senior majoring in public health and economics and a student of color, discomfort with those types of conversations translates to real life: “ It’s kind of a way of not associating with what’s going on.”

But, she says, it’s getting better. In a year in which LGBTQ rights and criminal justice reform have repeatedly made headlines, all social justice issues have become more visible.

“People do listen, over the last year people talk about them more," says Ketema. "Ever since Beyoncé came out on stage with that feminist sign, people have been interested in these types of things."

'Come Out Of The Library'

Recent graduate Streiff is a member of the Student Admissions Advisory Board. This week, there was an internal debate over what to do about questions about the riots that admitted students posted on the admitted students page (regular-decision applicants who have been accepted have until May 1 to decide whether to attend).

Some members of the board felt questions about the riots should be deleted, considering them irrelevant to campus life. Streiff couldn’t disagree more. But she says that debate was proof “we feel ourselves as a separate entity."

According to Streiff, one of the deepest and most consistent JHU pushes to uplift Baltimore -- free tuition for Baltimore public school graduates admitted to the university -- can be a source of resentment from other students, based on the assumption these students are less qualified.

Like a casually racist Yik Yak post hovering at the top of a feed, problematic attitudes persist, and students of color deal with the discomfort of not knowing whether the person sitting next to them in class is upvoting: “People like it and it’s allowed to exist,” says Ketema.

Ironic, when the #BlackLivesMatter movement itself is about the very right to black existence.

The university has a tendency “to express concern for the campus community in the face of immediate violence, but ignores structural racism, the disenfranchisement of the community and everyday experiences of oppression,” doctoral student Banahi says.

She wants the campus to acknowledge their effect on Baltimore 100 percent of the time, and not only when things get dire:

Johns Hopkins has initiatives for volunteering in the community, but not everyone takes advantage of them. “There are ways to help out, but you kind of have to look for [them],” says Ketema.

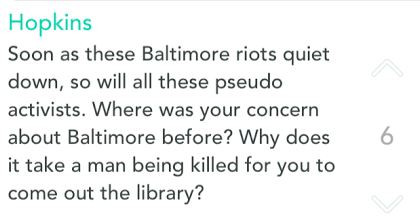

Several Yik Yak posts deride those who used this week as an opportunity to document their activism on Snapchat and Instagram, but whether those criticisms are directed at students of color or white “allies” isn’t clear.

Far From Right

Over the past decade, the school also has been criticized as a force for gentrification -- specifically, for plans to redevelop East Baltimore and a neighborhood called the Middle East. As Marisela Gomez -- who was schooled in the city through her Ph.D. at JHU and is the author of "Race, Class, Power and Organizing in East Baltimore" -- told Next City, in 2001 the university relocated black residents to pave the way to develop properties they already owned:

“There was an intention behind the project. ... It was becoming too unsafe for the Hopkins community. Making it safe meant moving out the black people, because that was what the public perceived as the problem.”

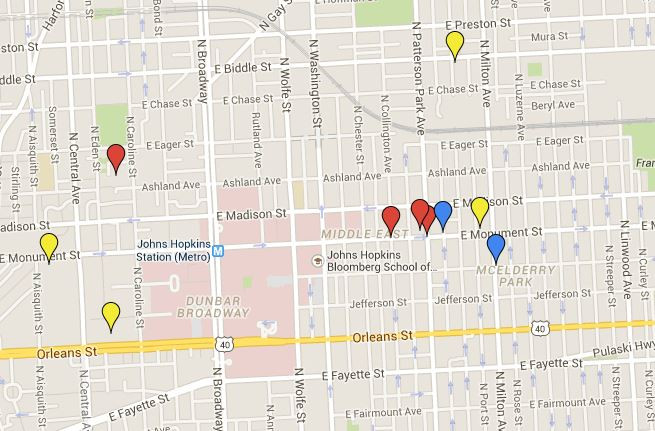

This crowdsourced map from civic hacker Shea Frederick and Hopkins data scientist Ryan Smith shows that the Middle East was a site for looting and fires on April 27 and 28.

The Next City deep dive into JHU’s development project also brings out that the school intended to create a “mixed income community” healthier than the one in place. But the mutual distrust Gomez hints at is a fixture in town-gown relations.

From a student’s perspective, it can be a self-fulfilling prophecy, says Ketema. She’s heard from other students that the community doesn’t like them, but hasn’t experienced that for herself. “People are always open to me,” she says.

There is no prototypical student experience. Streiff continues to be baffled as to why she was one of only two white students in a class on black politics, especially because she has nothing but glowing praise for the professor.

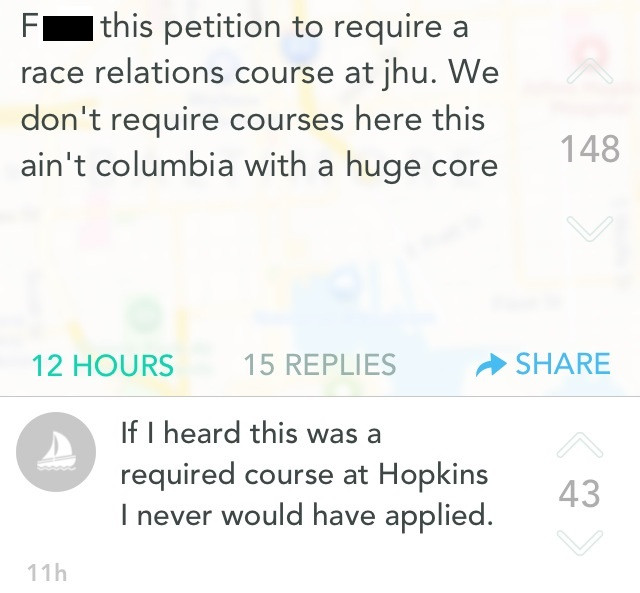

Yet, the second most popular post on Yik Yak right now slams the possibility that a class on race would ever be required:

Today, Ta-Nehisi Coates -- who last year wrote the Atlantic’s unforgettable cover story on racist housing policy -- addressed the JHU student body in a planned event that had been rescheduled, presumably because of this week's turmoil.

“Stop squirming, there’s nothing to squirm about," Coates said to those uncomfortable with their own privilege. "There’s a lot you can do right now, but there is very little you can do right now that will undo this long, long history. Your job is to do your part right now.”

Although the loudest Yak-ers may preach a less-than-perfect understanding of the black experience at JHU and in Baltimore, the future of town-gown relations will rely on the ability to listen.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.