Republicans Attacking Obamacare, One More Time

Republicans in Congress spent much of 2017 seeking to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. After repeated attempts failed, they celebrated a victory with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. While the tax bill left most of the ACA intact, it included the repeal of the ACA’s individual shared responsibility penalty, the penalty imposed on individuals who fail to purchase qualified insurance coverage.

That means the so-called individual mandate remains in the ACA but, beginning in 2019, individuals will no longer face a financial penalty if they choose not to purchase health insurance.

Health policy experts agree that this will destabilize the individual insurance market. With the ACA allowing people with pre-existing conditions to purchase health insurance at the same price as others, the individual mandate was a necessary counterbalance that encouraged healthy people to purchase insurance and stabilize premiums.

Emboldened by the legislative success of GOP tax reform, 20 states led by Texas and Wisconsin have renewed efforts to weaken and undo the ACA.

We study health policy and health care law and have watched the attacks on the law. We believe this latest legal challenge will likely fail but can still damage the ACA and insurance markets by exacerbating the uncertainty sown by actions of the Trump administration as the states-led suit meanders through the courts over the next years.

Death By A Thousand Cuts

The ACA has been under attack since it was enacted, but these attacks have intensified since the Trump administration took office and even more since congressional Republicans failed to repeal the ACA.

Cumulatively, the attacks have significantly weakened the law. Yet the law has persisted for almost eight years. And the most recent polls indicate that the ACA has never been more popular.

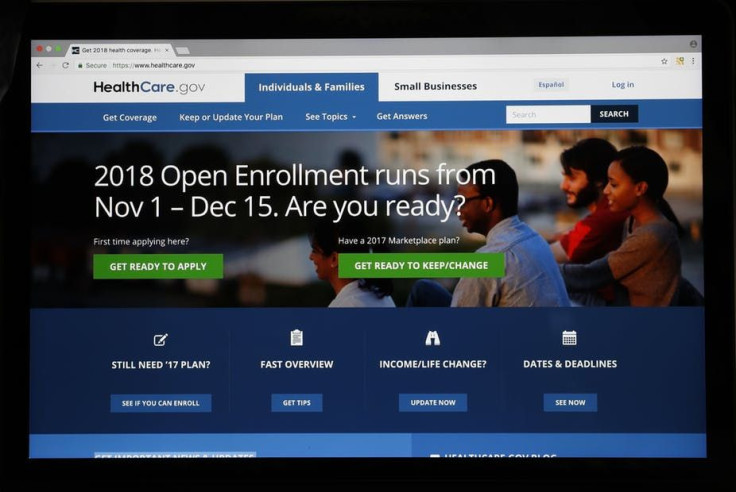

The Trump administration reduced outreach and advertising. It also ended cost-sharing subsidies in October. The administration also cut the number of days for enrollment to 45, significantly shorter than the first open enrollment. And, the website was down many Sundays, a popular day for enrollment.

But still, almost 12 million people enrolled during the most recent open enrollment period.

Major Previous Lawsuits

Since its passage in March 2010, the ACA has seen dozens of legal challenges. The very day the ACA was signed into law by President Obama, 26 states and others initiated the first major challenge to the ACA.

That lawsuit directly challenged the constitutionality of two core components of the ACA: the expansion of the Medicaid program and the requirement for individuals to purchase insurance or be subject to a fine.

Joining the court’s four liberal justices, Chief Justice John Roberts upheld the constitutionality of the individual mandate as a tax. However, he agreed with the plaintiffs that mandatory Medicaid expansion was unconstitutional.

The verdict, on June 28, 2012, damaged but preserved the ACA. Americans would be required to purchase insurance or face a penalty.

The expansion of the Medicaid program was left to the discretion of the states.

The next lawsuit took issue with the ACA’s requirement to provide certain forms of contraception to women. The Supreme Court sided with Hobby Lobby, Inc. in June 2014.

The court ruled that the ACA’s entire contraception mandate placed a substantial burden on closely held religious corporations. Various similar cases have been consolidated in Zubik v. Burwell. That case was sent back the lower courts in 2016 and is still pending.

King v. Burwell and Halbig v. Sebelius challenged the legality of premium subsidies for individuals purchasing insurance coverage through the federal insurance marketplace.

On June 25, 2015, the Supreme Court sided with the Obama administration in upholding the subsidies in a 6-3 decision.

Finally, in late 2014, the U.S. House of Representatives filed suit against the Obama administration over delays implementing the employer mandate and the payment of so-called cost-sharing reductions. These are reimbursements for insurance companies for payments they are required to make under the ACA to assist qualified individuals purchasing insurance in the insurance marketplaces for their out-of-pocket expenses.

The courts only allowed U.S. House of Representatives v. Burwell to move forward with regard to the cost-sharing reductions. However, the issue has become moot as the Trump administration has refused further payments to insurance companies.

Relitigating The Individual Mandate

With the repeal of the shared responsibility payment, the state attorneys general argue in their suit that the individual mandate is no longer a tax, and thus no longer constitutional.

The heart of the issue is what legal scholars call severability. When part of a law is deemed unconstitutional, courts must consider what should happen to the rest of the law – must it also be struck down or can it stand alone?

The Supreme Court previously was faced with this exact issue in the lawsuit filed in 2010. In its June 2012 ruling, the court rejected the Medicaid expansion as unconstitutional but still upheld the rest of the ACA.

This will be a critical question as courts hear this new legal challenge. If the individual mandate is now unconstitutional, then would Congress have still have wanted the remaining pieces of the ACA to persist? Alternatively, are there parts of the ACA that cannot stand without the individual mandate? This particularly applies to the insurance market reforms that came along with the individual mandate, like the requirements to sell insurance to all comers and at the same rates.

When the Roberts Court decided to uphold the remainder of the ACA while making the Medicaid expansion optional, the court stated that “we have no way of knowing how many States will accept the terms of the expansion, but we do not believe Congress would have wanted the whole Act to fall, simply because some may choose not to participate.”

We believe this has particular resonance with the current legal challenge. It seems clear to us that Congress would not have wanted the whole law or its protections to fall for everyone just because some Americans would choose not to participate.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article.

Simon F. Haeder is an Assistant Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University.

Valarie Blake is an Associate Professor of Health Law, West Virginia University.