Researchers Find Extensive Antibiotic-Resistant Genes Widespread In Bacteria That Attack Humans And Soil

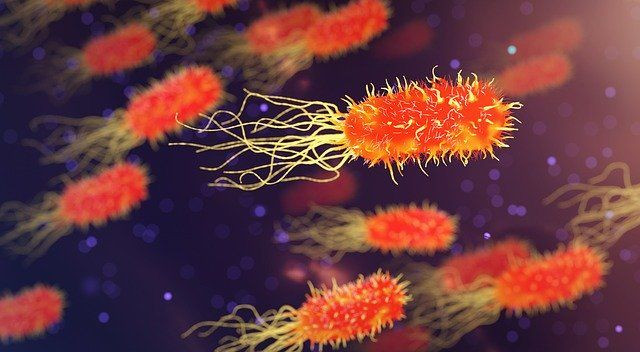

Genes representing a new method of antibiotics resistance are widespread in bacteria living in the soil and on people and some of those genes have the power of destroying all tetracyclines, reported a new study.

Tetracyclines- the first antibiotics that became available are broad-spectrum antibiotics with bacteriostatic activity. It works by binding specifically to a particular ribosome of the bacteria to inhibit protein biosynthesis. The current generation of tetracyclines is designed to thwart the most common ways bacteria resist these antibiotics.

The researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have created a chemical compound that shields tetracyclines from getting destroyed. When given alongside tetracyclines, the antibiotics’ efficiency was restored.

“We first found tetracycline-destroying genes five years ago in harmless environmental bacteria, and we said at the time that there was a risk the genes could get into bacteria that cause disease, leading to infections that would be very difficult to treat, the study’s co-senior author Gautam Dantas, Ph.D., a professor of pathology and immunology and of molecular microbiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis told News Medical.

The researchers were able to find them as soon as they started to look for these genes in clinical samples. This fact that these genes were found so rapidly explains that they are more widespread than previously thought.

“It's no longer a theoretical risk that this will be a problem in the clinic. It's already a problem,” Dantas told News Medical.

Five years ago, Dantas discovered 10 different genes that gave bacteria the ability to destroy the toxic part of the tetracycline molecule and inactivate the antibiotic drug. Those genes code for proteins that acted as tetracycline destructases. But the researchers weren’t aware of how widespread these genes were.

The Study:

Dantas and colleagues screened 53 soil, 176 human stool, 13 latrine, and two animal feces samples for genes similar to the 10 genes that they had already found. But they found out 69 more possible genes that destroyed tetracycline.

They cloned some of these tetracycline-destructase genes into E.Coli bacteria that wasn’t tetracycline-resistant to test whether the genetically-modified bacteria survived exposure to the antibiotics.

Findings of the study

- E. coli bacteria that got the destructive genes from soil bacteria inactivated tetracyclines

- E. coli that received the genes from bacteria associated with people destroyed all 11 tetracycline forms

- One of the tetracycline destructases that was found in human-associated bacteria might have evolved from an ancestral destructase in soil bacteria, but with better efficiency and a broader range

- Adding the chemical compound designed to preserve the potency of tetracyclines made the bacteria two to four times more sensitive to all three of the latest generation of the antibiotic drug

"Our team has a motto extending the wise words of Benjamin Franklin: 'In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death, taxes and antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance is going to happen. We need to get ahead of it and design inhibitors now to protect our antibiotics, because if we wait until it becomes a crisis, it's too late,” Timothy Wencewicz, Ph.D., an associate professor of chemistry in Arts & Sciences at Washington University told News Medical.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.