With The Right Guiding Principles, Carbon Taxes Can Work

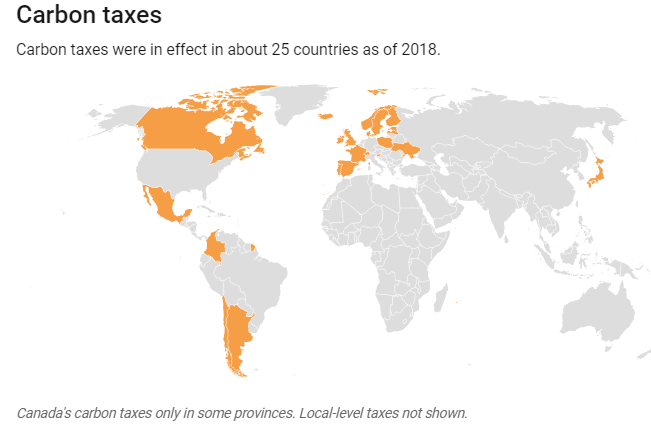

Like most economists, I favor taxing carbon dioxide to cut carbon pollution.

A carbon tax makes fossil fuels like oil and coal more expensive. That, in turn, leads consumers and industries to use less of them. At the same time, it boosts demand for alternative energy sources like wind and solar powered electricity.

With the anti-regulatory Trump administration in power and a Republican majority controlling the Senate, however, no such national policy is imminent. Prospects for statewide efforts may look bleak too, after ballot initiatives in Washington state that would have created the nation’s first carbon tax failed in 2016 and 2018.

But other states may move in this direction. Having conducted extensive research about how climate policies are working around the world over the past decade, I believe that the effort to enact a carbon tax is worth it.

The headwinds

Based on my experience serving as the deputy assistant secretary for environment and energy at the U.S. Treasury Department for two years during the Obama administration, I recognize it won’t be easy to enact tough climate policies. Recent events in France underscore this fact. There, President Emmanuel Macron has backed down on the taxes on gasoline, diesel and heating oil that led to waves of so-called yellow vest protests that rocked France and left six protesters dead by mid-December.

Fairness is central to the French protests, which sprang from objections to what came across to many voters as an elitist, out-of-touch central government that has lowered taxes on the rich while hiking taxes on the poor. The 2018 French budget, enacted last December, cut corporate tax rates and wealth taxes while increasing a social levy on all income similar to our payroll taxes. This change skewed taxes away from the rich and made the poor pay more.

This law had already stirred discontent. The hike in fuel taxes, part of a carbon tax initially enacted in 2014, poured fuel on those flames. Framing the increase as an environmental tax did nothing to assuage rural and low-income voters. “We’re not anti-environmental,” a movement organizer said. “This is a movement against abusive taxation, period.”

Meanwhile, the failure of the Washington State ballot initiative illustrates the risks of trying to enact controversial policies at the ballot box. When vast amounts of money poured into the state from big oil corporations like BP to finance a campaign against a carbon tax, thoughtful policy debate was forced to compete with a slick media campaign. Supporters also had to overcome the legacy of a previous failed referendum that pitted climate policy advocates against each other.

The benefits

Designed correctly, a carbon tax can do more than reduce carbon pollution. It can also make tax codes more fair. Research by a group of economists demonstrates that carbon taxes can be progressive – meaning higher income households pay more in tax per dollar of income than lower-income households.

A carbon tax can also create jobs. Although instituting one in the U.S. would surely speed up the disappearance of U.S. coal mining jobs, that shift would continue no matter what while also expediting the creation of new employment opportunities. As of today, there are more than twice as many jobs in solar technology than in coal mining.

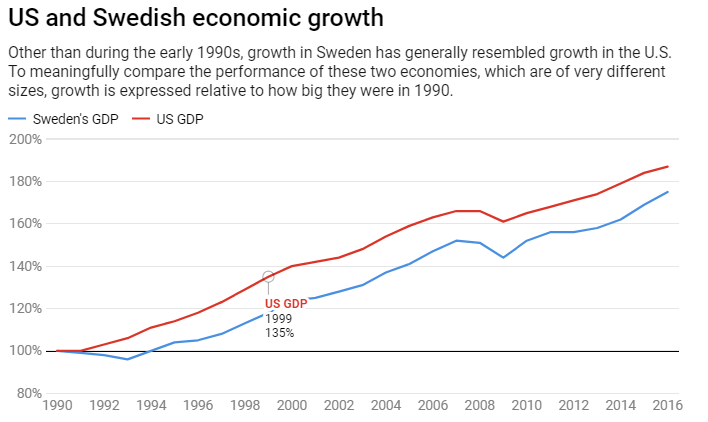

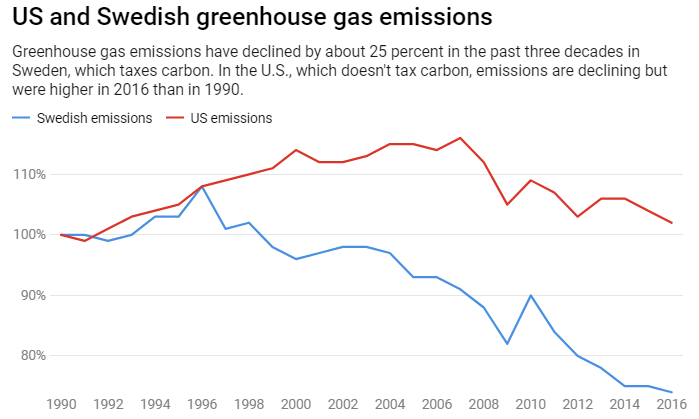

Finally, taxing carbon is unlikely to hurt the economy. Despite a roughly $135-per-ton tax on carbon dioxide, Sweden is doing just fine. Its GDP has grown by nearly 80 percent since it enacted a carbon tax in the early 1990s, while its emissions have fallen by one-quarter.

Sweden’s growth rate has actually exceeded that of the U.S. since 2000 despite high taxes on carbon pollution, in part because Sweden uses the revenue to cut other taxes. And the World Economic Forum finds the two economies to be about equally competitive.

Likewise, British Columbia’s carbon tax has not hurt its economy since going into effect in 2008. My analysis indicates, if anything, the tax has boosted growth in the Canadian province. That’s because some of the revenue raised was used, to cut marginal income tax rates on individuals and the tax bills for small businesses. Another economist based at the University of Calgary found that local employment increased by a small but statistically significant amount.

Politically feasible

When and if Congress is finally ready to enact a carbon tax in the U.S., it should consider a guiding framework as it debates the elements of the new tax.

President Ronald Reagan understood the power of establishing frameworks to guide tax policy. In his 1984 State of the Union address, he called for a tax reform that would raise no additional revenue but “make the tax base broader, so personal tax rates could come down, not go up.”

With that directive, Reagan launched the most significant tax reform in the history of the tax code. His directive made clear that he wanted lower tax rates without sacrificing revenue. This simple framework imposed an important discipline that kept lawmakers on track.

In my new book, “Paying for Pollution: Why a Carbon Tax Is Good for America,” I lay out similar guiding principles. In my view, carbon taxation should be revenue-neutral, make the tax code fairer, streamline climate policy and lead to significant emission reductions.

Republicans and Democrats have argued for years over the size of the federal government. It is a debate that should not ensnare climate policy. Revenue neutrality in this context means that all the money raised through a carbon tax should be returned to Americans through some combination of tax cuts and direct payments.

Fairness means that low to moderate income households are not made worse off by the tax. There are many ways to do this including a proposal from the Climate Leadership Council, a policy initiative backed by big corporations like ExxonMobil and General Motors as well as three big environmental groups and former Republican secretaries of State James Baker III and George Shultz, to give all U.S. households the money raised from carbon taxation through carbon dividends.

The government should also provide transitional relief to carbon-intensive industries and regions. The federal government should partner with state and local governments to develop transition plans for these communities.

National climate policies generally include various tax breaks for renewable energy as well as mandates – which in the U.S. primarily consist of state-level renewable portfolio standards. With a carbon tax, it is possible to eliminate some of these overlapping policies and guarantee that emissions decline at the same time.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the whole point of climate policies and therefore the highest priority when implementing them. As the latest U.N. climate report makes clear, cutting carbon pollution everywhere and quickly is an urgent priority. And the Swedish track record suggests that pricing carbon dioxide can help make it happen without hindering economic growth.

Gilbert E. Metcalf is a John DiBiaggio Professor of Citizenship and Public Service; Professor of Economics, Tufts University.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.