Road To Rio: London’s Uncertain Olympic Legacy Calls The Promise Of Rio Games Into Question

As Rio gears up for its controversial Olympic games, we examine the extent to which the most recent Olympic host, London, delivered on promises of a lasting economic legacy.

LONDON — The stadium at the heart of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park glitters in the evening light, a white jewel set among the lush paths and winding waterways of surrounding parkland. This stately effect is compounded by Anish Kapoor's twisting metal sculpture flanking the stadium, stretching hundreds of feet into the air — and underscores the extent to which the Olympic project has transformed this once-dilapidated part of east London.

Conventional wisdom has it that London's hosting of the 2012 Olympics was a success: The games were delivered under budget, at a cost of 8.7 billion pounds ($12.7 billion), saw U.K. athletes deliver outstanding performances and, according to a 2013 government assessment, had a positive economic impact. The U.K. government claims that 70,000 new jobs were created as a result of hosting the games, and £28 billion ($40.5 billion) to £41 billion ($59 billion) in gross value will be added to the British economy by 2020.

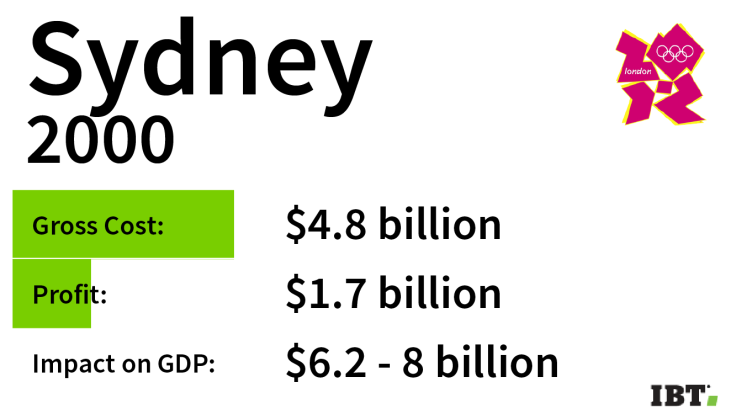

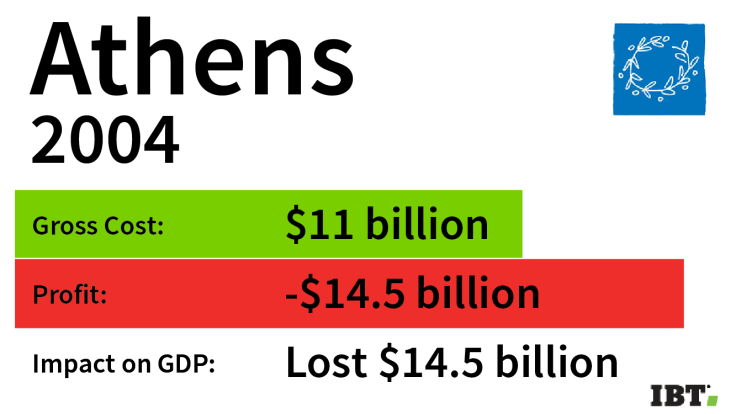

Other recent host cities cannot say the same. Athens is littered with decaying relics from its 2004 games, which ended up costing between $14-$15 billion — massively over their $4.6 billion budget — helping bankrupt the country. Montreal's 1976 games ran $1.4 billion over budget, leaving the city with a debt it took 30 years to pay off. Sydney's games in 2000, which cost $4.8 billion, were found in a later study to have reduced Australian household consumption.

Then there is the case of the Russian resort of Sochhi, whose 2014 Winter Olympics were the costliest games ever, coming in at around $38.93 billion. Most egregious amongst those games' costs were the stadium and public transport infrastructure — which remain massively underused while costing Russia's federal government $1.2 billion a year to maintain.

These lessons have not been lost on potential host cities like Boston, which have concluded that hosting the games isn't worth the expense.

For London, the most recent summer Olympics host, however, the legacy of the games is not all state-of-the art facilities and gold medals. With just a few weeks to go until the starter's pistol is fired in Rio's Olympic games — the prohibitive cost of which has stirred up great anger in a nation with entrenched poverty — aspects of London's experience may not augur well for the legacies pledged by the Brazilian organizers.

Critics are already questioning how these promises will, or can be, delivered on. The organizers have admitted that plans to clean up the body of water for the Olympic sailing competition — described by some as an “open sewer” — will not come to fruition. In addition, plans to pursue urban regeneration projects in some of Rio's poorest favelas, or shanty towns, have been drastically scaled back.

London's dreams of urban regeneration did not quite live up to the five pledges made in the city's Olympic bid. The economically deprived neighborhood around the stadium has undoubtedly been transformed -- but experts are questioning thecost to longstanding residents.

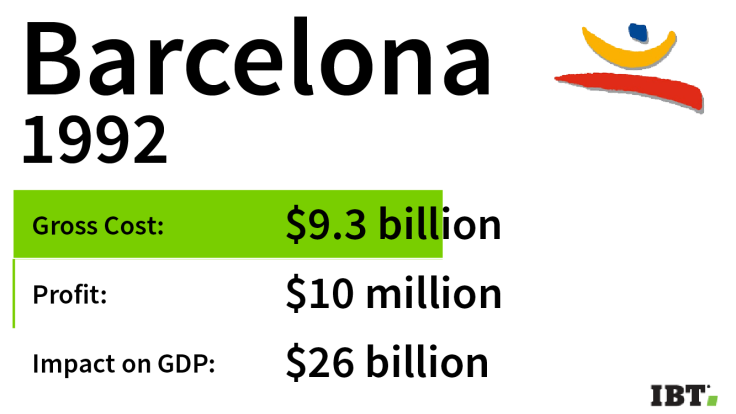

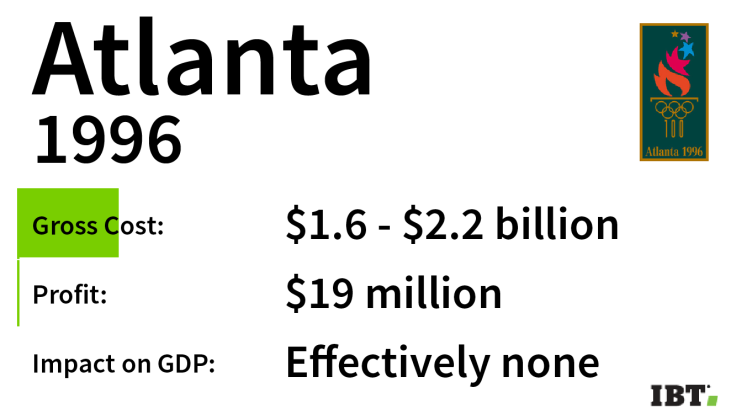

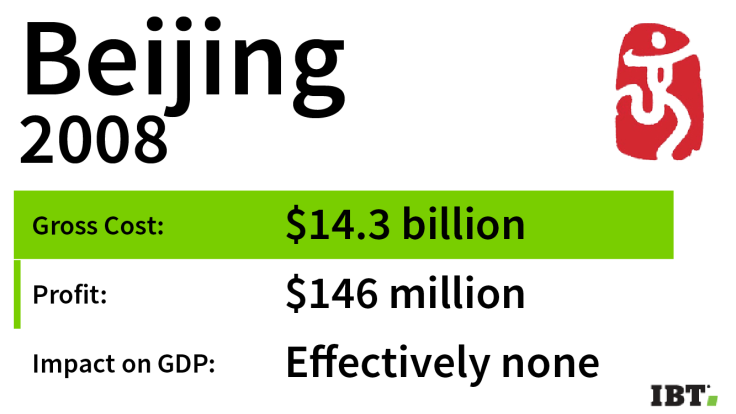

Olympic Cities: Who Was A Winner?

Click through to see how much Olympic host cities made— or lost.

“[Gentrification] is inevitable,” Ralph Ward, a former planning and regeneration advisor for the Olympics at the Department for Communities and Local Government, told International Business Times.

“If you make an area more attractive, the prices are going to go up. That's just supply and demand. And as prices go up, the people who can't compete are the local community, who are relatively low paid. The tragedy of East London is that to some extent, the Olympics has this aura about it and the problem is solved, but actually what it's done, for some people, is to make life a lot worse,” he said.

Affordable housing, a scarce commodity in a city where property prices regularly set world records per square foot, also appears to be an area where promises made before the London games have failed to deliver.

“There are a number of new towers being built on the fringes of the park [that] include either no or very low levels of affordable housing. Even when affordable housing is included, these tend to be intermediate, with ‘affordable’ housing on one scheme requiring a 65,000 pounds ($94,700) minimum income,” said Penny Bernstock, co-director of the London East Research Institute and head of sociology and social policy at the University of East London.

“In a sense you've got these two worlds developing. You've got people living in the park ... and just walk across the road and you'll see the housing misery building up. It hasn't delivered on affordable housing,” she said.

As a result, some of the area's longtime residents say that unemployed people struggle to get government-funded social housing, a process one Stratford resident described to the Guardian as "social cleansing."

Both Ward and Bernstock, as well as other experts IBT spoke with, acknowledged that the games had left positive legacies in improving facilities and employment opportunities for local people, but said the number of jobs created was not enough to justify the initial pledges.

And the sporting legacy of the London games, something the bid team and the government strongly touted in advance, has had decidedly mixed results.

The results of the Active People survey — which measures the level of participation in sports across the U.K. — have been lauded by senior figures behind London's Olympic bid as showing an increase in sporting participation in the wake of the games. The official report says that 15.74 million people 16 years or older played sports at moderate intensity for at least 30 minutes at least once a week — which it says is 245,200 more people than the interim result reported six months ago, and 23,200 more than a year ago, an increase of 1.65 million people in the last decade.

On closer examination, however, the numbers are not that impressive. The number of people 16 and over taking part in sports in the country rose from 2012-13 to 2014-15, but is still lower than the 15.89 million that participated in 2011-12.

Experts say assertions that hosting the Olympics will increase grassroots participation in sports are fundamentally flawed.

“You need to be careful when you examine to what extent the games delivered this or that, because if you don't have a specific strategy designed to leverage the opportunities created by the games, very little is going to happen,” Vassil Girginov, a reader in sport management and development at Brunel University in London, who has done extensive research on the legacy of the London games, told IBT.

The participation figures call into question the extent to which Olympic success managed to inspire ordinary people to get involved in the sports that received a great deal of attention.

“Swimming and athletics are classic examples,” said Griginov. “Both sports did very well in the Olympics in terms of [U.K. athletes'] success, yet their participation rate has gone down. The whole premise that there is a straightforward causal relationship between hosting the Olympic Games and increased or decreased participation in sport is false, because it assumes a straightforward causal relationship and doesn't take into account a myriad of other factors.”

Despite the broken promises, the majority of experts IBT spoke to viewed London's Olympic experience as successful and said Rio would do well to learn from London's mistakes.

“I think the basic story is good,” Ward told IBT. “But it's not the story that we led the public to think was going to happen. My main message would be: Don't look at the promises. Look at what has happened and judge that on its own terms.”

The result of these discrepencies is manifesting itself in an increasing global disinterest in becoming an Olympic host city. Boston withdrew its bid for the 2024 summer games, and four cities have withdrawn their bids to host the 2022 winter games. Enthusiasm for the games, such as it still exists, appears to be driven less by promises of lasting legacies or massive profits, and more by prestige and politics.

Despite the enormous cost involved, hosting the games and the international exposure that comes with it is still attractive to voters in many countries. In 2013, the International Olympic Committee found that public support for hosting the games was around 70 percent in Tokyo, 76 percent in Madrid and 83 percent in Istanbul, the cities bidding in that year to host the 2020 summer games.

Even Londoners, famed for their ability to complain about everything from the weather to their local football team's performance, were not immune to the feelgood factor. A poll carried out at the end of 2012, after the glory of the games had vanished, found that almost 80 percent of Londoners thought the games were worth it, and that they "did a valuable job in cheering up a country in hard times."

That's a result that would be as good as gold for Rio.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.