Road To Rio: The Race Is On To Build The World’s Fastest Olympic Swimsuit

There’s a new swimwear-tech arms race underway — one where the difference between victory and defeat in the pool (and within a $1 billion swimwear market) can come down to comfort and a hundredth of a second.

The competition will be fierce during the swimming events at this summer’s Olympics in Brazil. An established titan will be fighting to maintain dominance as a longstanding rival reaches for success. And a plucky upstart that’s been turning heads aims to make a splash like never before.

These aren’t Olympic swimmers. These are the sportswear companies designing the swimsuits the swimmers will be wearing.

Seven years after swimming’s governing body banned controversial high-tech swimsuits that had upended the sport and led to accusations of “technical doping,” there’s a new swimwear-tech arms race — one where the difference between victory and defeat can come down to the feel of a fabric, the stretch of a suit, and a hundredth of a second in the pool.

On Friday, U.K.-based Speedo, long the biggest name in Olympic swimming, unveiled the suits its sponsored swimmers will be wearing at the games. “The Speedo federation suits look so eye-catching, dynamic and powerful that our athletes will no doubt hit the blocks with confidence, empowering them to look, feel and perform their best,” Jamie Cornforth, Speedo’s vice president of product and marketing, said in a release. But the swimwear giant won’t be the only brand name on the starting blocks in Brazil; the Italian company Arena Water Instinct, Speedo’s fiercest competitor, has been closing the gap in terms of technology and sponsorships. Both operations have employed cutting-edge research and global networks of swimmers and coaches to develop suits that they say offer unparalleled boosts — both technical and psychological — to the swimmers wearing them.

These rivals are facing an unexpected threat: When swimming icon Michael Phelps came out of retirement in 2014, he chose not to rekindle his longtime relationship with Speedo or join forces with another established brand, but instead launched “MP,” his very own swimwear line.

Whether years of effort and millions spent in research and design pay off for each of these three operations will be determined over two competition-packed weeks in Rio de Janeiro this August. What’s at stake isn’t just who wins medals and who doesn’t. Which logos are on the suits that grace the podium could significantly impact market shares of the estimated $1 billion competitive and fitness swimwear market, one that’s fueled by a growing number of baby boomers opting for laps in a pool instead of running or other high-impact exercises. While none of these suits will turn a hobbyist into a gold medalist, the right Olympics-burnished brand could make a person feel like a winner — leading them to spend $300 or more for the hottest attire in swim racing.

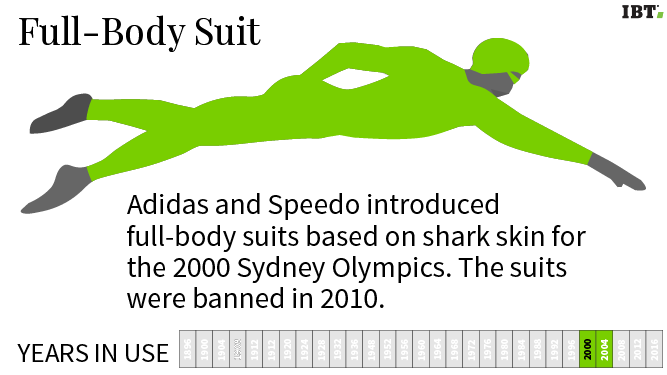

Rubber Suits to Carbon Cages

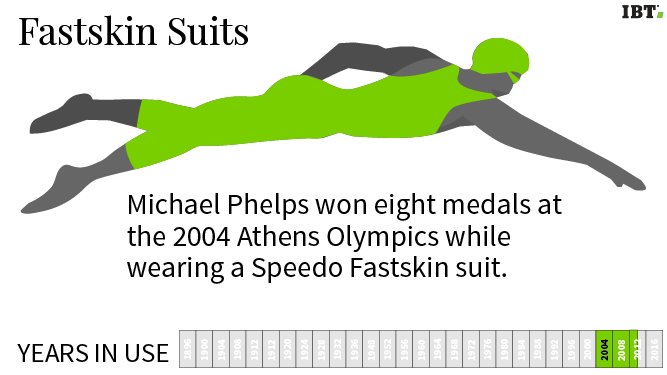

In early 2008, Speedo unveiled its “LZR Racer” swimsuit line, launching the age of the “rubber suit.” The body-length suits featured nonpermeable materials like polyurethane that turned swimmers into sleek tubes and trapped air beside the body, increasing buoyancy. Other companies, realizing the technological advantage of such an approach, followed Speedo’s lead, and soon nearly all competitors were wearing similar designs. In less than two years, swimmers set more than 130 world records — raising questions about whether such accomplishments had more to do with what the competitors were wearing than actual abilities.

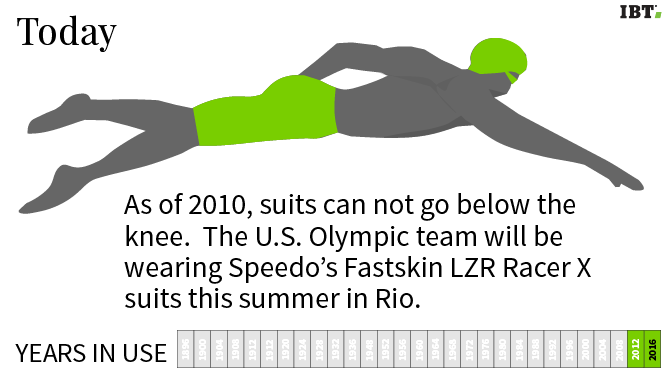

That’s why in July 2009, the International Swimming Federation, or FINA (Fédération Internationale de Natation), wiped the slate clean, requiring all competitive swimsuits to be made of air-permeable fabrics and be kept between the knee and navel for men and knee to shoulder for women. The new rules also prohibited fastening systems, like zippers, that had allowed swimmers to put on super-tight outfits.

The changes rocked the industry. Many brands had been building on Speedo’s nonpermeable bodysuit designs, but now, with everyone starting from scratch and with far fewer tools and approaches at their disposal, the only companies that had a real shot at designing new Olympic-caliber suits were those with the most resources and know-how. That included, alongside Speedo, the 43-year-old Italian competitive swimwear company Arena, founded by the son of the founder of Adidas.

“We hit a new technological era,” Giuseppe Musciacchio, Arena’s general manager for brand development, said in a phone interview from the company’s headquarters in Tolentino, Italy. “It has become more difficult for all the brands in the market to create something that is really a competitive suit. It’s why in high-level competition, you only see a few brands now, which are Arena, Speedo and TYR. And in this very moment, it’s really a big fight between us and Speedo.”

While Arena had wholeheartedly embraced the rubber suit trend, even upping the ante with a pure polyurethane suit compared to Speedo’s hybrid approach, looking back, Musciacchio believes the ban was the right choice for the sport. “It had been a time when technology had been taking over the world of swimming,” he said. “We were handling the kind of technologies that could really change the values in the pool.”

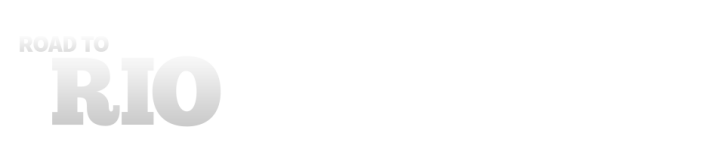

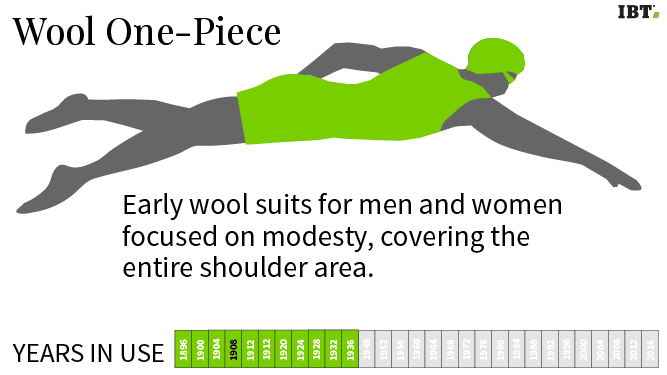

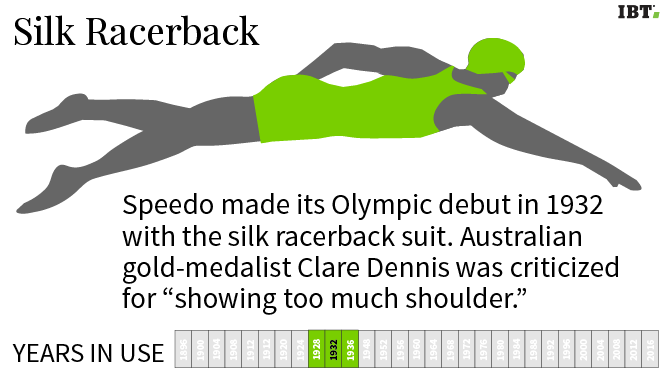

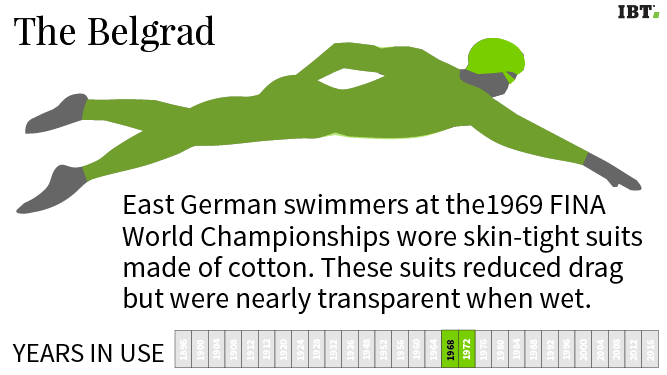

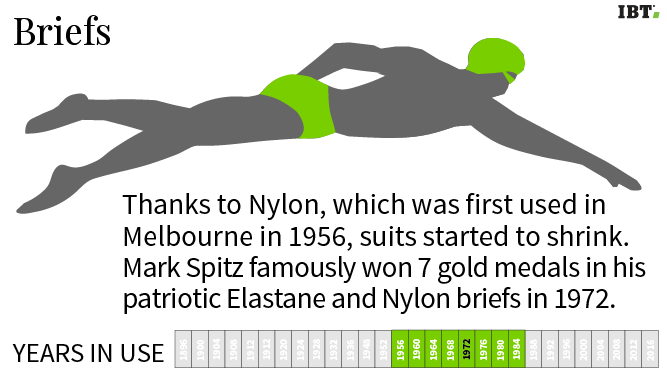

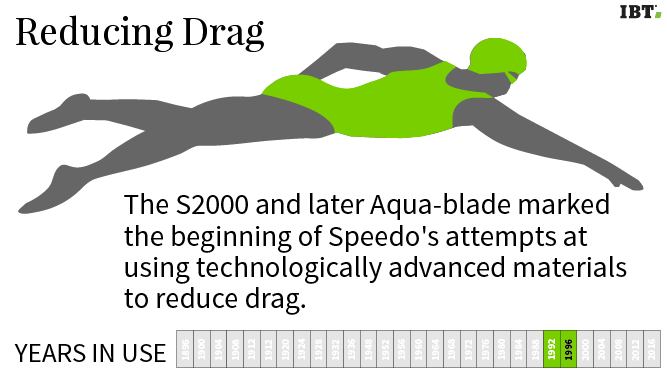

Click through to see how swim suits have advanced

But while FINA had outlawed high-tech suits, it couldn’t take away what companies like Arena had learned while making them. “The polyurethane suit age had left us with a much, much deeper knowledge of the potential effects and interactions of the body moving in the water and the suit the swimmers are wearing,” said Musciacchio. “In a way, it was like we had to cook dinner and the list of possible ingredients we could use was dramatically cut. But our skills to cook the right things were much higher.”

To start cooking, Musciacchio and his small team of designers began asking themselves how they could recreate the compression effects of plastic suits without resorting to now-banned plastics. They hit on carbon fibers. While carbon fiber-reinforced clothing was already being used in bike racing because of its tear-resistant and anti-static properties, Musciacchio and his colleagues realized that by weaving carbon-fiber cages into their swimsuits, they could limit how far their textile fabrics could be stretched. “The role of the carbon is to lock out, like a seatbelt in your car,” said Musciacchio. “When you stretch a Lycra fabric, you can stretch it to more than 100 percent of its length. When you add in carbon fibers, they lock it at a certain level.” Suddenly, with the launch of the Powerskin Carbon-Pro in 2012, Arena once again had a high-compression suit made with legitimate materials.

The concept was a hit, leading to subsequent iterations such as Carbon-Flex and Carbon-Air. Then, in March 2016, in the lead-up to the Olympics, Arena unveiled Powerskin Carbon-Ultra, which Musciacchio said is likely “the technological limit of where we can push the technology.” The new suits — the most expensive on the market, with a retail price of $399 for men and $549 for women — boast three times the amount of carbon fiber than before. But they also feature a new suit design developed not just through high-tech tests (such as scrutinizing test subjects’ movements and vital signs as they swam in infinity pools, and tracking the water resistance and drag of suited-up “test dummies” strapped into underwater centrifuges) but also by examining the personal needs of dozens of elite athletes that Arena works with all over the world.

“We listened to them telling us, ‘When you want to become an Olympic champion, the training is important, what you eat is important, sleep is important, but the most important thing is the strength you have within you,’ ” said Musciacchio. “What we asked ourselves was, ‘How can we turn this interesting insight into a product?’ ” They did so by developing an internal suit structure that connects and supports key muscle groups while still allowing freedom to rotate.

While other brands have also begun to incorporate carbon into their suits, Musciacchio insists they’re missing something: a deep knowledge of how to best work with such textiles for maximal results. “You need a lot of experience to understand the tension of each of the threads woven into the fabric,” he said. “One of my teammates is a guy who has been with the company since 1973, Michel Joseph. Now 72, he has participated in the development of every suit in this company. The knowledge of someone who has been crafting suits for nearly 50 years of his life is incomparable.”

Such experience has paid off. According to Musciacchio, at the 2011 World Aquatics Championships in Shanghai, swimmers in Arena swimwear won 46 medals, compared to 80 medals by those in Speedo suits. By the 2015 championships in Kazan, Russia, those numbers had been nearly reversed: Arena netted 73 medals to Speedo’s 56. At the same time, Arena has been luring away big names from squads that have long been associated with Speedo, such as members of the Australian Olympic swim team.

“Arena has 40 years of history, while Speedo has slightly more than 80 years of history,” said Musciacchio. “We have to catch up. But I can tell you, we are closing.”

Getting in the Zone

Speedo, however, shouldn’t be counted out. After the 2009 shake-up, the venerable brand’s research and design team went back to work at Aqualab, the department at Speedo’s Nottingham, England, headquarters, charged with a single mission: Design the world’s fastest swimsuits. They brought in experts ranging from aircraft designers to nanotech experts to sports psychologists. They built computerized models of professional swimmers and subjected them to virtual swim meets. They dreamed up suits that looked straight out of a superhero movie.

The result, in 2012, was the Fastskin Racing System, an arrangement where redesigned swim goggles and caps worked in concert with a new version of the LZR swimsuit, LZR Racer 2, that featured fewer compression panels and covered less of a swimmer’s body, as required by the new FINA rules. Technically, the system was a success, but it wasn’t a commercial blockbuster. “It might have been too much newness, too quickly,” Tim Sharpe, Speedo’s head of design and innovation, told International Business Times in a phone call from England. “There was a completely different feel to the fabric. We got that feedback that it wasn’t quite feeling right. So we said, ‘Right, let’s go back and look at what didn’t feel right.’ ”

For the next iteration of its LZR swimsuits, Speedo worked with more than 300 elite swimmers and nearly two-dozen swimming experts from 26 countries, analyzing how their designs affected swimmers not just physically but also psychologically. “We prototyped up the suits, tested them out, figuring what felt right, what didn’t feel right, and why it didn’t feel right,” said Sharpe. “We ended up with a massive bank of data from which we were able to pull major insights.”

They found that the one-size-fits-all approach to racing suits didn’t work for everyone. Some competitors wanted less compression in their suits; for these swimmers, Speedo continued to offer its LZR Racer 2 line, which felt lighter on the body. Others wanted more compression, as long as it made them still feel fast and flexible. This led to the design of LZR Racer X, featuring extremely high-compression fabric that stretched in just one direction, meaning it compressed horizontally around muscles in the hips, glutes and quads while allowing the legs freedom to move up and down. The suits also boasted ultrasonically welded “X” seams that weren’t just for show: They were designed to enhance links between core muscles and encouraged proper body position in the water. Finally, the female version of the suit had one layer of fabric cut away at the abdomen, to emphasize and reinforce core abdominal muscles. The result, said Sharpe, was a suit that was “not just physically fast but [also] emphasized the psychological feeling that comes with feeling you are fast.”

The special editions of the LZR Racer X and LZR Racer 2 Speedo unveiled on Friday for Speedo-sponsored Olympians this summer — such as Missy Franklin, Nathan Adrian and Ryan Lochte — feature new print designs, but the design of the suits themselves remains unchanged. That, according to Sharpe, was a conscious decision. “This is the first time we have launched a suit as early as we have in terms of an Olympic schedule,” he said. “We learned from 2012 that swimmers had to get to know the suit so they could be comfortable in it and at ease. They need to be completely in the zone, and having trained in the suit they are now racing in, they can get into that zone.”

Breaking All the Rules

Despite Arena’s and Speedo’s best planning, chaos was introduced to the equation in August 2014 when Michael Phelps, returning from retirement, announced that he and Hall of Fame coach Bob Bowman were launching their own competitive swimwear line, MP. They were doing so in partnership with Aqua Sphere, an Italian company that since its founding in 1998 had focused much of its efforts on developing radical new ideas for swim eyewear, like wraparound swim masks, but had never dabbled in competitive swimsuits. In fact, said Todd Mitchell, Aqua Sphere’s California-based business line manager, “When we started conversations with [Phelps and Bowman], neither of them knew who we were, even though we had become the No. 2 swim-goggle company in the world.”

But Phelps and Bowman weren’t looking for a known quantity in the racing scene; they were looking for an outsider operation willing to shake things up. “A competitive swimming company would have never invented the swim mask,” said Mitchell. “It takes a less restrictive view of what swimming is to allow you do things differently. [Phelps and Bowman] felt they could do things differently than anyone had done it in the past, and better. And we were the vehicle to help them do that.”

Brainstorming, researching and testing at Phelps and Bowman’s training center in Baltimore, Aqua Sphere’s design team began to reimagine the concept of competitive swimwear. For starters, Phelps wanted low-profile swim goggles that allowed him increased range of vision so he could better see lane lines, his competitors and the crowds cheering him on. After spending months working with patented curved-lens technologies, the team was able to develop a competitive goggle with several additional millimeters of peripheral vision. “It sounds minute, but it’s a big deal when you have a goggle that’s so small,” said Mitchell.

Swim caps were another concern. According to Phelps, typical caps had a tendency to wrinkle during competition, leading to increased drag. Using 3D models of Phelps’ head, the team developed a cap with thicker silicone panels on each side to hold it firmly in place.

Then, of course, there were the swimsuits themselves. Phelps had come to believe other swimwear companies had become slaves to the concept of compression. “He said he felt like a penguin,” said Mitchell. “He said, ‘Give me a suit that has hydrodynamic properties, but I want flexibility. I want something I can swim in more naturally.’ ”

The lack of flexibility wasn’t the only complaint leveled against high-compression suits. It often takes a half hour or more for swimmers to properly squeeze into such outfits. “Races can be a high-stress environment,” said Mitchell. “Now you have this added component that you have limited time to put on this suit, and if you put it on wrong, it can rip.”

The swimsuit solution came from Aqua Sphere’s swim goggle team in Italy. The company had recently combined two different materials to ensure their eyewear was both water-tight and comfortable. They took the same hybrid approach for their swimwear, leading to the MP Xpresso suit, involving the fusion of two fabrics: a high-compression material in key areas of the suit and a more flexible material elsewhere.

Not only did the resulting swimsuit take just 10 minutes to put on, it also appeared to boost performance: While wearing the Xpresso suit and his other MP equipment at the 2015 U.S. National Championships, Phelps swam the fastest times of the year in 200-meter individual medley, 100-meter butterfly and 200-meter butterfly.

Results like that were heartening to the folks at Aqua Sphere. “Obviously, Michael and Bob have extremely high standards for themselves and everything associated with them when it comes to swimming and performance,” said Mitchell, a former competitive swimmer who never imagined he’d be working with one of the biggest names in the sport. “It’s motivation. There is excitement that comes with working with the best, and there is pressure that comes with that, too.”

Phelps, the only potential MP-sponsored competitor in Brazil, still has to qualify for the competition at the Olympic trials in June in Omaha. But if he does, it will raise the stakes for what’s already the biggest showdown in the world of competitive swimwear. “For us, the work is done now,” said Sharpe at Speedo. “It is now up to the athletes. They are the ones who win the medals. All we can do is give them the best chance we can.”

But even after the competition wraps up in Rio, none of the swimwear companies will take much time to relish their victories or recover from defeat. “There is certainly no sigh of relief,” said Mitchell. “The next Olympics is only four years away.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.