Russian Coders, Ukrainian Cybercriminal, Mexican Smugglers, And The Largest Cybercrime In History

What do two young Russian coders, a Ukrainian cybercriminal and two Mexican fake credit card smugglers have in common?

No, it’s not the beginning of a insensitive ethnic joke. All five people have been linked to one of the largest cybersecurity breaches in history. One of them may have been mistakingly identified, but that hasn’t prevented him from being swept up in investigators’ wide net.

The day before Thanksgiving, unknown cybercriminals launched a coordinated strike against the Target (NYSE:TGT), the second-largest discount retailer in the United States. The attackers first broke into a Target Web server and uploaded malicious software to the point-of-sale machines that Target employees use in checkout lines. The software collected two things: the information contained within the magnetic strip of every credit and debit card swiped, and personal information from Target shopping accounts.

In the first two weeks of the holiday shopping season – including Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year -- the thieves made off with 40 million credit and debit card records. Another 70 million account profiles – which include the names, mailing addresses, phone numbers and email addresses of Target shoppers – were also stolen. Some say that attack is the biggest cybercrime against a single retailer in the U.S.

It wasn’t until Dec. 19, four days after the attack was over, that Target admitted the security breach and assured the public that it would find the person or people responsible.

“We take this matter very seriously and are working with law enforcement to bring those responsible to justice,” Target CEO Gregg Steinhafel said in a statement.

The hunt was on, and on Jan. 16 the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Secret Service, the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center, and cyberthreat intelligence firm iSIGHT Partners published a joint report that identified the malware as Kaptoxa (a Russian slang word for potato; pronounced Kar-Toe-Sha).

The following day, Los Angeles-based cyberintelligence company IntelCrawler announced that it had traced the “BlackPOS” malware to its source. IntelCrawler published detailed information on how it reverse-engineered the malware to find that it was authored by the codename “ree4,” a hacker who earned money by programming tools for the hacker community, hacking social media accounts, and training other hackers in performing attacks designed to take down Internet services.

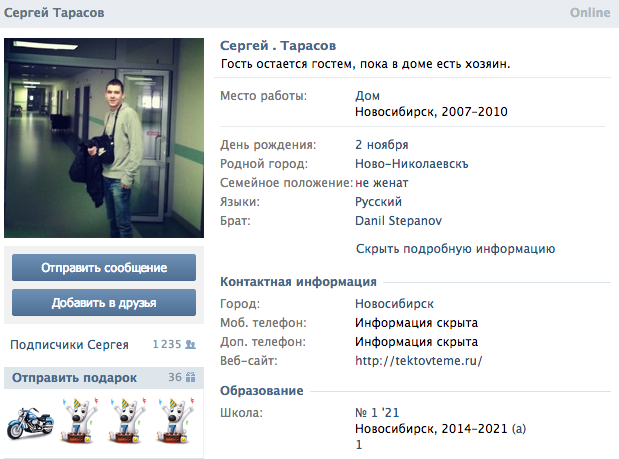

Using Russian social networks, IntelCrawler concluded that ree4 was the pseudonym of Sergey Tarasov, a 17-year-old Russian hacker with roots in St. Petersburg. Tarasov denied the accusation in Russian media outlets, stating that although he enjoys writing code for personal use, he doesn’t have the hacking know-how to create the Kaptoxa malware. He also said that he has no connetion to St. Petersburg.

Brian Krebs, who originally broke the story about the Target hack on his website, said he was skeptical about Tarasov’s involvement.

“They named the wrong guy,” said Krebs, who worked as a reporter for the Washington Post for 14 years before using his self-taught computer skills to start an independent computer security blog, Krebs on Security. His own research into the BlackPOS malware led to a different conclusion.

“If you are going to cover this news, it should be done so with a dose of skepticism,” Krebs told journalists who asked for his take on the IntelCrawler report.

This didn’t stop many news outlets from running with the story, and soon the teenager was synonymous with “Target hacker” in Google searches.

“Well, what can I say,” Tarasov told Russian news website Tjournal, according to a rough Google translation. “Our media grabs information and gives it to the masses without checking beforehand.”

Tarasov has reportedly hired a lawyer and refused to answer questions about his participation in hacker forums, but it’s hard to argue against his point. The IntelCrawler report had not been verified by other security firms or law enforcement agencies (possibly to avoid interfering with an on-going investigation).

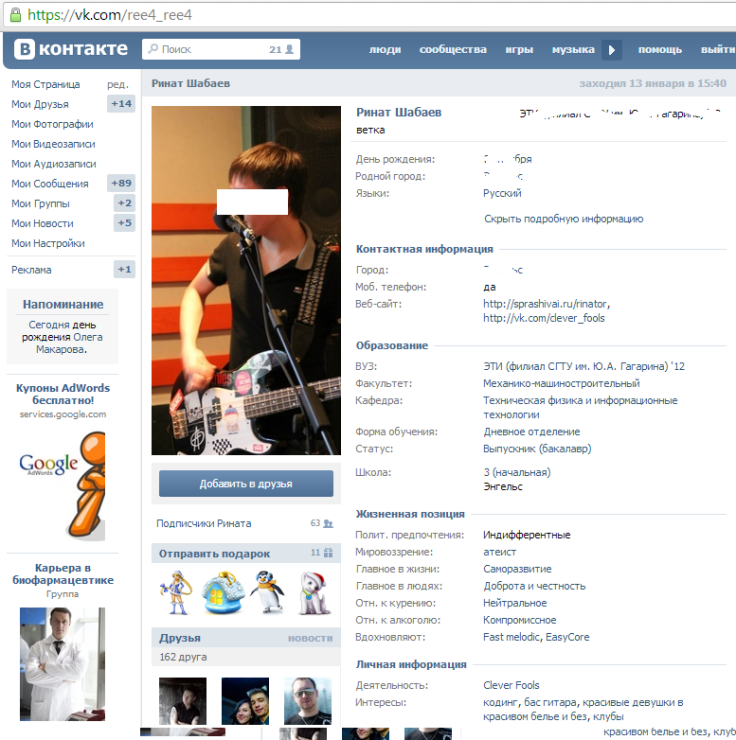

Tjournal also reported that on VK, a European social network especially popular among Russian-language speakers, the username and email address “ree4” was used by another young Russian man, 23-year-old Rinat Shabaev.

Just three days after its initial report, IntelCrawler apparently changed its mind. The company revised the report to say that Shabaev was the real author behind the BlackPOS malware used to attack Target, and that Tarasov was acting as technical support.

Krebs agreed on Twitter that this conclusion matched his own research, but told IBTimes that he has not looked into Tarasov’s involvement.

So Intelcrawler apparently just changed its mind about the guy responsible for the Target POS malware. Now they have the right guy

— briankrebs (@briankrebs) January 20, 2014“These guys rarely work alone,” Krebs said. “In this case, I really don’t know one way or the other.”

Recent reports have abandoned the story of “the teenage hacker,” and now focus on the “Russian punk-rocker with a programming hobby.” Shabaev even discussed his involvement in the malware in a video interview with Russian news site, Lifenews.ru, saying that he didn’t invent Kaptoxa but did write an extension that allowed the BlackPOS malware to operate undetected on Target’s machines.

Like many programmers, Shabaev draws a distinction between writing the code and how the software is eventually used.

“If you use this program with ill intentions, you can make pretty good money, but that’s illegal,” Shabaev said, adding that the software could have also been used for benign purposes and that his only intention in writing the code was to sell it. “That’s why I didn’t want to use it. I just wrote it for sale. Let other people use it so it’s on their conscience.”

Neither Shabaev nor Tarasov have been charged with any crime. In the U.S., writing code, even for malware, is protected as free speech, though distributing and using it may be illegal.

If that’s the case, then charges may fall on someone known online as “Rescator.” Rescator operates multiple illegal stores online and is a top member of Russian- and English-language crime forums. Since the attack, Rescator’s stores have been busier than usual selling cards (for as much as $135 per card) that were linked to Target.

Not only is Rescator profiting from the stolen data, but the cybercriminal may have been involved in the creation of the BlackPOS. Kreb’s analysis of the malware’s code turned up Rescator’s name in strings of text, and this finding has since been supported by McAfee.

Krebs traced Rescator to Andrew Hodirevski, a young man living in Odessa, Ukraine. When Krebs contacted Rescator to verify his findings, Rescator offered $10,000 to bury the report.

While the trail of bread crumbs in the malware’s code leads to Eastern Europe, the only arrests made in connection with the Target hack have been on the other side of the world.

Daniel Dominguez Guardiola and Mary Carmen Vaquera Garcia, two Mexicans with outstanding arrest warrants for credit and debit card fraud, were arrested in McAllen, Texas for carrying 90 fraudulent credit cards. Authorities eventually seized 22 more from the pair and linked the data on the cards to information stolen from Target customers.

There is no evidence linking any of these five people with the actual attack on Target. While the arrests of Guardiola and Garcia could reveal information leading to the hackers, the fact is that information belonging to as many as 110 million Target shoppers is already being sold on the Internet.

Fake credit cards are the least of people worries. The information taken from the 70 million Target accounts can be used for identify theft.

Nieman Marcus Group was also attacked, resulting in another 1.1 million stolen cards. Reuters also reported that the same malware is currently being used against six other U.S. retailers, exploiting weak security guarding the computer systems.

Looking at the tangled but undecipherable web that was behind the Target attack, odds are that there will be many more data leaks before retailers can sell consumers a real promise of privacy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.