Russians Worry For Their Savings As Ruble Tanks

When she saw the ruble go through the floor, Natalia Proshina made a beeline for the bank.

Like countless other Russians, she feared her savings would vanish overnight in an economic crisis precipitated by western sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine.

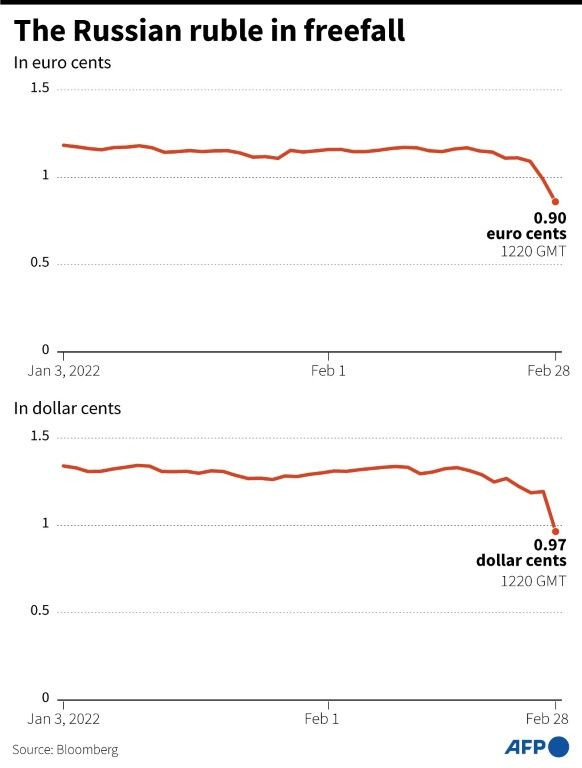

On Monday, the Russian currency plummeted to a historic low, falling to 100 against the dollar and 109.4 against the euro.

The tanking ruble revived unpleasant memories of financial instability of the 1990s, when millions of Russians saw their savings evaporate under the effect of a devaluating currency and soaring inflation.

"As soon as I saw the ruble nosedive, I rushed to the bank," Natalia explained.

The retired 75-year-old, who used to be a journalist on Soviet-era television, kept her money in VTB, Russia's largest bank after Sberbank.

The West slapped sanctions on both state-owned financial institutions when Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine last Thursday and Sberbank's European subsidiary is already on the verge of collapse.

Natalia said she rushed to withdraw her cash "to avoid losing my entire fortune", just as she had in the 1998 financial crisis.

"We lost all our money then, including everything my husband had earned abroad," she lamented.

"I don't want to play this game with the state any more... They could declare martial law at any minute and confiscate my savings (for the war effort)," the one-time Soviet propagandist muttered furiously.

Outside Natalia's bank in central Moscow, Alexander Zuyev, who works in the culture industry, waited his turn to see his account manager.

"I think it's pretty reasonable to withdraw cash, given the current climate," the 40-year-old opined.

"We all have to look after ourselves, seeing as we have no idea what this country is going to come to."

Fidgeting behind him in the queue, 51-year-old retired soldier Edward Sysoyev was losing patience.

He tried to get cash out of another branch of VTB but couldn't.

While there is as yet no major rush on the banks, Edward thinks panic is not far off.

"Ninety percent of Russians are going to rush to withdraw their rubles and change them into dollars, property or even gold," he predicted.

"It'll be ordinary people who pay for this military bun-fight," he said grimly of President Vladimir Putin's decision to attack Ukraine.

Rustam Iakovlev is also expecting mass panic.

"Even if the central bank tells us everything is OK, people are going to spook and withdraw their cash," the 50-year-old engineer from Moscow forecasted.

"If I had any, I'd have taken the lot out."

On Monday, the Russian central bank hiked its key interest rate from 10.5 to 20 percent, after struggling for four days to "stabilise the situation" via interventions on the currency markets.

In the northwestern city of Saint Petersburg, Putin's birthplace, a dozen or so customers hovered outside a subsidiary of Austria's Raiffeisen bank.

Svetlana Paramonova, 58, was among those waiting for the branch to open its doors.

She said she was going to take her money home and keep it there.

"It's safer there, given we haven't a clue what's going on any more," she concluded.

Her neighbour in the queue, Anton Zakharov, had a similar plan.

"No-one has any confidence in the powers that be or in the banks," the 45-year-old explained.

Economic analysts are divided over the potential for more widescale public uproar as Western sanctions bite.

The instability of the ruble will "undercut Russians' standard of living over the next 12 months", Alexei Vedev of the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy told AFP.

Be as that may, the authorities might still keep a lid on the situation.

"Russian discontent will only boil over if people's living standard drops to a third of the current level," said Sergei Khestanov, macroeconomic adviser with dealer Open Broker.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.