S. Korean Regulators In Constant Search For Porn

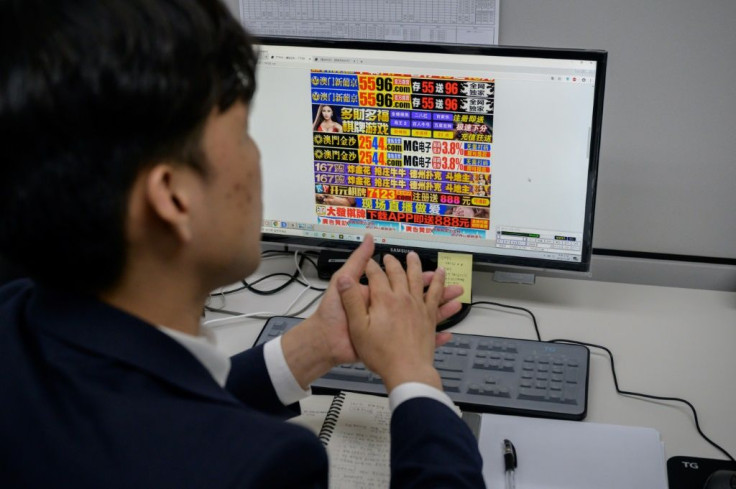

In a drab government office in Seoul, a team of broadcast regulators spend their days watching online porn -- the front line troops of South Korea's attempts to crack down on spycam videos that mostly expose women.

The 16-member digital sex crime monitoring unit was set up this autumn by the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC), with a mission to hunt down and remove sexual videos posted without consent. As of last month it operates 24 hours a day.

Known as "molka", spycam videos are largely shot by men secretly filming women in schools, toilets and elsewhere.

The taskforce also targets "revenge porn", private sex videos filmed and shared without permission by disgruntled ex-boyfriends, ex-husbands, or malicious acquaintances.

In the highest-profile example, star K-pop singer Jung Joon-young was arrested in March on charges of filming and distributing illicit sex videos without the consent of his female partners. His court verdict is due next week, with prosecutors demanding seven years' imprisonment.

The twin phenomena have become increasingly widespread in the hyper-wired South, driving tens of thousands of women to demonstrate against them in the streets of Seoul last year, chanting "My life is not your porn" and demanding authorities take action.

Sitting at their desks, the KCSC staff -- most of them assigned from other roles at the commission, and four of them women -- have the cautious manner of government bureaucrats.

An Hyeon-cheol came through this year's competition for highly-coveted government jobs at the KCSC, when there were 146 applicants for each available position, but his duties are a far cry from what he expected.

"It was difficult to maintain my composure," the 27-year-old said of his first days as a civil servant. "I saw many provocative pictures of a kind that I had never seen before in my life."

The head of the monitoring team Lee Yong-bae told AFP: "When I went outside, I could not look at women around me because pictures I saw in the office overlapped in my mind's eye. I had to keep my head down."

To find the material, they search for Korean-language hashtags on domestic and international platforms -- including Twitter and YouTube -- that reference sexual acts, although sometimes key terms are disguised with asterisks.

They can instruct South Korean sites to take down suspect videos, but the vast majority are hosted on overseas servers beyond their jurisdiction -- when they tell domestic internet service providers to block access, but can only ask the foreign operators to remove them voluntarily.

The taskforce took action 82 times a day in October on average -- eight times as many as the regulator did four years ago, before the dedicated unit was set up.

Ordinary commercial porn -- which is illegal in the South and access to it blocked -- is not part of their remit.

Sometimes panicking victims contact the taskforce themselves on a KCSC hotline, 1377, asking for help.

"We recently had a victim who gave us 100 different site addresses where a sex video secretly shot by her ex-boyfriend was uploaded," Lee said, acknowledging that completely removing a video was "nearly impossible" with material being disseminated and shared online at the press of a button.

One spycam video first posted in May spread to more than 2,700 sites in six months, a KCSC document shows.

The first day after initial upload was the "golden time" to intervene, said Min Kyeong-joong, secretary general of the KCSC, after which repostings are likely to "spiral out of control".

"Our mission is to contain the spread in the first 24 hours," he said. "For the victims, every second is a heart-wrenching moment."

In the conservative South, women who appear in such videos will feel deep shame despite being the victims and face the threat of ostracism and social isolation if the videos become known to those around them.

Nearly 5,500 people were arrested for such offences last year, up 22 percent on 2016, police data showed -- and 97 percent of them were men.

Park Yu-na, 31, told AFP she now routinely avoids using public toilets "as much as possible".

"I and other women share this fear that we can fall victim to spycam crimes anytime, anywhere," said the Seongnam resident.

The KCSC taskforce was set up after President Moon Jae-in acknowledged the spycam issue last year, calling for tougher punishments and saying: "We as a society have failed to fully recognise the trauma and humiliation suffered by those victimised."

Filming or distributing intimate videos without consent can each be punished with up to five years' jail, but analysts say many often end up with only a suspended sentence or a fine.

"There is this tendency where watching illegal sex videos is tolerated as just another form of men's entertainment, compounded with weak punishment," said Lee Na-young, professor of sociology at Chung-Ang University in Seoul.

The South's patriarchal culture "suppresses pragmatic sex education", added Bae Bok-ju, a member of the National Human Rights Commission, so that many men "grow up thinking there is nothing wrong with watching illegal porn as long as they don't put it into action".

Some argue against controls on spycam videos as an infringement of freedom of expression, said KCSC secretary-general Min.

"When I listen to such claims, I want to ask them this: Would you say the same thing if it was your wives or daughters?"

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.