As Saddle Ridge Hoard Gold Coins Are Set To Hit The Market, A Rare Coin Expert Talks About How Numismatics Has Evolved To Boost Investor Confidence

UPDATE, March 5 -- The Los Angeles Times quoted a U.S. Mint official saying there is no evidence linking the Saddle Ridge Hoard to a theft cited in a Jan. 1, 1990, report in a tade newspaper.

UPDATE, March 4 -- The coins discovered by a northern California couple may have been stolen from the San Francisco Mint, according to an old iron and steel trade newspaper report dated Jan. 1, 1900. The evidence is compelling these coins were stolen as a result of an inside job at the Mint. SFGate reported on Monday about this fascinating revelation about the origins of the $10 million Saddle Ridge Hoard.

Original story begins here:

On Thursday, the first coins from the Saddle Ridge Hoard will go on public display at the National Money Show in Atlanta, a three-day annual event that attracts coin collectors from across the country seeking to spend modern cash on some old and collectible currencies.

Featured prominently this year will be some pieces from what is believed to be the largest single discovery of buried treasure ever unearthed in the United States. A year after a Northern California couple discovered on their property eight decaying, rusty cans filled with gold coins dating from the late 19th century, collectors will soon be able to start buying the pieces on Amazon.com or from Kagin’s, a rare-coin seller based in Tiburon, Calif., that was commissioned by the anonymous owners of the treasure to organize the sale of the pieces. The average value of each coin from late 1800s is estimated to be more than $7,000.

It’s the kind of story that spurs imagination: A couple walking their dog and serendipitously discovering a lost cache from the past, buried by some unknown person for unknown reasons, someone who never made it back to recover what he (or she) so carefully stashed away so many years ago.

There are professional treasure hunters whose obsessions become part of the story of uncovered riches, as was the case of the late Mel Fisher and his tragic 16-year search for the Atocha Motherlode, a $450 million cache of 17th century Spanish colonial booty found in 1985 in 22 feet of water off the Florida Keys.

Then there are the hobbyists with their metal detectors you sometimes have seen digging holes in parks and on beaches hoping to find a lost doubloon or other historical artifact. In December, retired Canadian security specialist Bruce Campbell was engaging this hobby on Vancouver Island and discovered a 16th century English silver shilling that has rekindled a controversial theory that explorer Sir Francis Drake, not Capt. James Cook, was the first European to visit what would later become British Columbia. In this case the coin’s modest price of $500 to $1,000 in the collector’s market is outweighed by its potential historical value.

So what exactly do you do when you find an old coin in grandmother’s attic or happen upon a stash of lost or forgotten booty? Well, the first thing you do is look up a numismatist and figure out exactly what you have and how much it’s worth.

The U.S. live auction market for collectible coins is estimated to be about $500 million dollars.

“That’s just for live auctions of U.S. coins,” Brian Kendrella, president of Stack’s Bowers, the New York-based rare-coin and currency auction house that generates about $300 million in sales annually through Internet-based and live auctions, sales to dealers and retail, says. “We know that when you include the eBays of the world and when you include dealer-to-dealer or coin-store business, and the trade in collectible paper currencies and the trade in collectible coins from all over the world, the numismatic market in the U.S. alone is in the billions of dollars.”

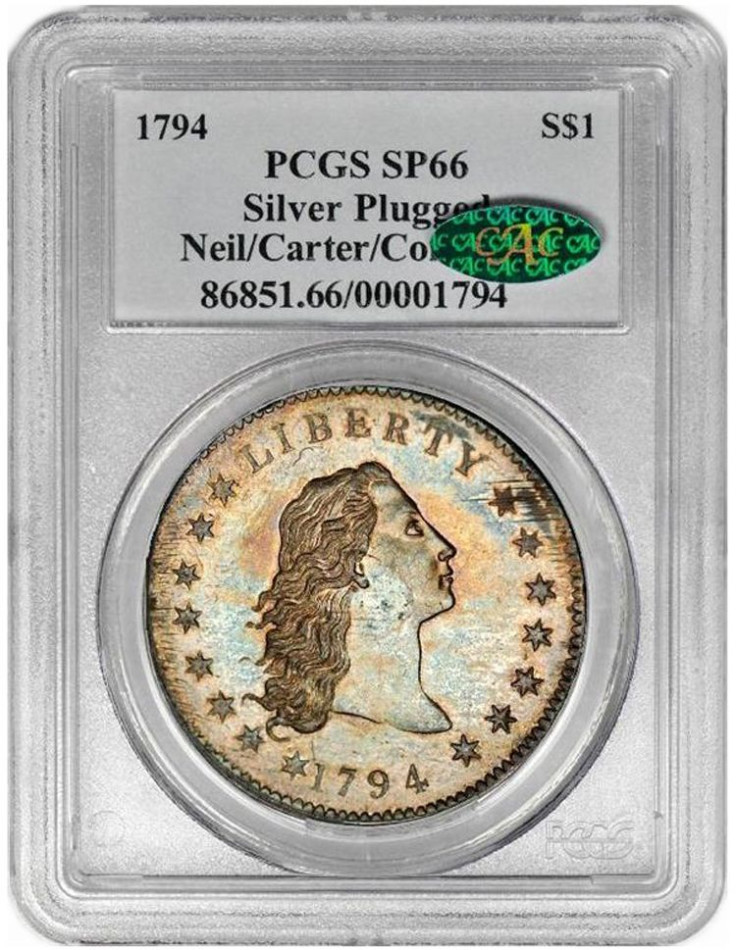

In January 2013, Stack’s Bowers received national attention for selling the most expensive single coin in history, a 1794 silver dollar that went to an anonymous buyer for $10 million dollars, the total combined estimated value of the Saddle Ridge Hoard’s 1,427 gold coins. The coin was minted in the first year that the U.S. began minting silver dollars, and its pristine condition suggests it might have been carefully preserved by its makers, suggesting it could be the first silver dollar ever produced.

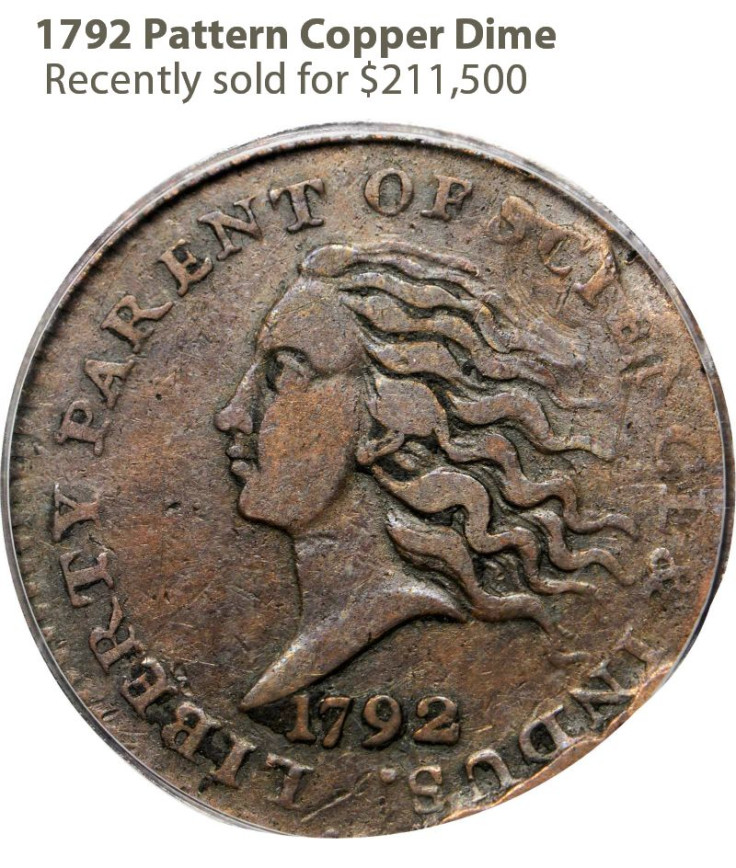

Earlier this month, Stack’s Bowers hosted an auction of American-themed coins in a conference room at the Director’s Guild of America in Midtown Manhattan. The wintery weather kept attendance in the auditorium low, but in a modern live auction, most bidders are online anyway. During that three-day auction, a buyer snatched up a 1792 copper American dime. It might have been worth 10 18th-century cents, but this month the coin sold for $211,500. Like many high-rolling auction bidders, the buyer remains anonymous.

International Business Times sat down with Vicken Yegparian, a numismatist for Stack’s Bowers, to discuss how the market in collectible coins has changed in recent years.

IBTimes: My grandfather once gave me a silver dollar. I still have it in storage somewhere. How much is it worth?

Yegparian: A lot of people get collectible coins like that, they’re given to them. In your case it depends on the condition and the year. That silver dollar might not be worth more than the silver content is worth, which is about $15.

IBTimes: That’s a bummer.

Yegparian: We often disappoint people who come to us with their coins.

IBTimes: Numismatics is not exactly a household name. How does one become a numismatist?

Yegparian: I’m the youngest of four boys. My eldest brother was a coin collector. He got me interested in this and we would go to banks looking for silver half dollars. Silver coins have not been circulated since the late 1960s. Most silver had already been taken out by people knowing that the coins were worth more than their face value. We would go [in the 70s] to banks looking for silver half dollars. Many people weren’t aware at the time that there were still silver coins mixed in with the junk-metal ones. One time I pulled out this roll and every single one of the coins was silver. Needless to say I was jazzed about that.

IBTimes: This industry is pretty big in dollar terms. Are people buying these coins as hobbyists or is there an investment quality to this in the same way people might buy art pieces, jewelry or classic cars as equity?

Yegparian: People come at it from different perspectives. Basically, it’s a hobby. In the 150 years of active collecting in the U.S., the value of rare coins as an investment has waxed and waned. What’s interesting is that the amount of information available today has made it more comfortable for the average collector and for investors to jump into the fray. Before, a lot of information was in people’s heads, difficult to obtain, etcetera. With the advent of the Internet, this information is more easily accessible. Fourteen years ago when I started I would get people asking me where they can find information about the value of their coins. I would tell them, “We’re not there yet. There are websites out there, but I don’t know how useful or reliable they are.” Now there is so much information out there on the Web, in peer-to-peer chat groups and other online forums, that people can piece together information about their coins and how much they’re worth.

IBTimes: Has this helped prevent fraud? Are collectors now more able to detect scams?

Yegparian: A significant part of that, especially in U.S. numismatics, is third-party grading. Grading standards have evolved for coins. The grading services in the mid- to late-1980s really pushed to codify the standards.

IBTimes: Who does this?

Yegparian: It’s like GIA [Gemological Institute of America] certificates for diamonds. You have grading services in this country that will grade and authenticate coins. You can see our coins are in these plastic encapsulations. We don’t do that. We send coins out or we receive coins already certified and encapsulated. There are two major ones and a slew of other ones, some of which are better or worse -- you get what you pay for. The two main ones used by Stack’s Bowers are PCGS [Professional Coin Grading Service] and NGC [Numismatic Guaranty Corporation].

IBTimes: It looks like you can’t open this plastic box without proving that it’s been tampered with.

Yegparian: Exactly. The only way to open it is to break it open and you can’t put it back together. The point is to keep the certification insert with the coin and to give the buyer the security of knowing that the certification goes with that particular coin.

IBTimes: You can’t handle the coin itself without opening the box. I would want to touch the coin, but I guess investors want to preserve that proof of the coin’s value.

Yegparian: This is an advent of the last 30 years. It’s a relatively new phenomenon, but it has given greater confidence to those who aren’t experts, who don’t have the time to invest in building the knowledge needed to authenticate a piece. That’s given a lot of stability to the market in recent years. Back in the day it was a problem.

IBTimes: What is an example of past attempts to defraud collectors?

Yegparian: Using your example of your grandfather’s silver dollar. If you took an 1893 silver dollar, even in well-worn condition it’s worth hundreds of dollars. If you were to glue an S-mint mark [a tiny letter “S” that indicates the silver dollar was minted in San Francisco] making it into an 1893-S silver dollar, you just fraudulently added thousands of dollars of value to the piece. This kind of thing was common before the advent of standardized grading services. We don’t see that kind of thing happening very often anymore, because if someone is paying thousands of dollars for one of these coins it will have been graded and encapsulated.

IBTimes: Have you noticed a marked rise in interest in this trade in Asia?

Yegparian: We started our auctions in Hong Kong in December of 2010. We brought great collections of Asian coins with us, but we also entered that market taking the American business model of an auction house and a reliable system that helped us quickly become the biggest auctioneer of Asian pieces in Hong Kong. We’re spoiled in the U.S. We took our hits and made our mistakes and developed a good grading system over time. Coin collecting has been around for a long time, and it’s certainly well developed in Europe, but the U.S. took it to the next level. Now buyers in these emerging markets can jump right in to a reliable system of trading.

IBTimes: You must get a lot of amateurs and hobbyists coming to you with their finds. You suggested before that many people can end up being disappointed to learn something they dug up isn’t really worth as much as they had hoped. Can you give an example of someone who just came to you off the street with something they found that ended up being something of value?

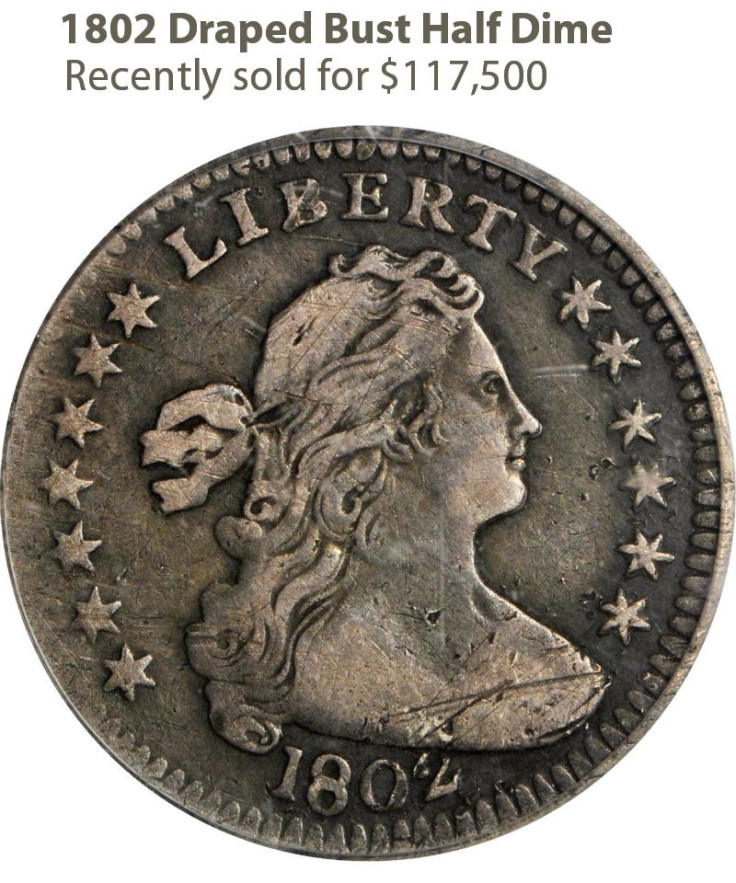

Yegparian: Rare American colonial-era coins come to us quite frequently. A few years ago an office building was being built next to the ground where the first U.S. mint in Philadelphia used to be. Some guys figured out where the construction workers were dumping soil from the construction site. They metal detected the soil and came up with some things that most probably -- it would be difficult to prove, but probably -- came from the first U.S. mint. They started making coins there in the early 1790s and these guys had a 1793 half-cent. It was corroded but you could tell it was in mint condition when it went into the ground, something that was dropped outside of the mint doors or discarded for some reason. There was another piece that was a piece of scrap copper that had a silver dollar imprint. They were probably testing the dies used to print the coins and then chucked the piece out the window. To a collector today that’s an awesome find.

IBTimes: These are obsessed people. They figure out a mint was at a location, they learn a building is being constructed nearby, they following construction workers to where they’re dumping soil ...

Yegparian: Well, it’s treasure hunting! It’s the lure of pirate gold. There are millions of serious collectors out there.

IBTimes: There’s also debate out there about getting rid of coins eventually and replacing paper currency with polymer-based fiat currency, like Canada did last year. I suspect you are pro-coin.

Yegparian: Yes, but I think we’re realists. I would love for there to be coins forever, but I guess one day coins will disappear as we know them. I think there will always be collectors.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.