San Francisco's Race For Robo-taxis Cleaves Sharp Divide Over Safety

A driverless taxi slows down on a dark San Francisco street and is quickly surrounded by a group of masked figures.

One of them places a traffic cone on the hood of the car. Its hazard lights flick on, and the car stops in the middle of the road, disabled.

This bizarre scene has been repeated dozens of times across the US tech capital this past week -- the work of activists protesting against the proliferation of robot cars, which they consider unsafe.

"We believe that all cars are bad, no matter who or what is driving," said the activist, who asked to be referred to by the pseudonym Alex to protect his identity.

His anti-car activist group, "Safe Street Rebel," is radically pro-pedestrian and pro-bike, and not impressed by widespread claims that driverless cars are a "new revolutionary mode of transportation."

Alex sees their arrival "just as another way to entrench car dominance."

Using traffic cones stolen from the streets, the activists have been disabling driverless taxis operated by Waymo and Cruise -- the only two companies currently authorized in San Francisco.

Their resistance has gone viral online, racking up millions of views on social networks at a time when state authorities are mulling the expansion of driverless taxi operations in the city to a full 24-hour paid service.

The proposal by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), which oversees autonomous taxis in the state, would allow Waymo and Cruise to directly compete with ride-sharing apps such as Uber or Lyft -- but without drivers.

But the issue has caused friction between state and city officials.

Driverless cars were first introduced in San Francisco in 2014 with a mandatory human "safety driver" on board.

Four years later, California scrapped its requirement for a human driver to be in the car, meaning it is no longer the stuff of sci-fi to cruise past a Jaguar without a driver on the streets.

But lately, San Francisco officials are worried by an increasing number of incidents involving autonomous cars.

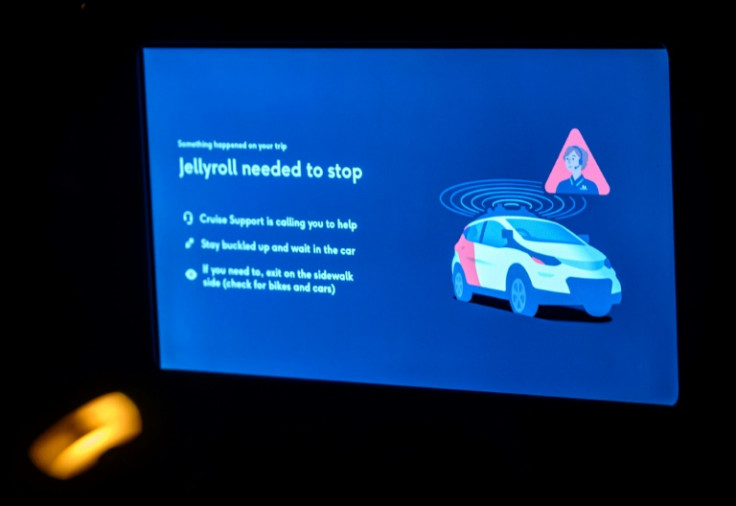

Allowing robots to take the wheel has led to cars getting stuck in the middle of roads, blocking bus lanes or even interfering in a police crime scene.

No fatal accidents involving humans and Cruise or Waymo vehicles have been recorded, though a Waymo taxi was reported in June to have killed a dog that ran into the street.

City supervisor Aaron Peskin condemned the CPUC's "hasty decision" to allow a "massive ramp-up" of driverless taxis on San Francisco's streets.

The San Francisco County Transportation Authority sent a letter to the CPUC, detailing 92 incidents involving autonomous taxis last year.

And the mounting controversy seems to be having some effect.

A critical decision by the CPUC on whether to further expand Waymo and Cruise's services was due by the end of June, but has been postponed twice, now to August 10.

For now, Cruise is only authorized to charge customers for routes driven between 10 pm and 6 am. Waymo cannot charge for rides without a human driver on board.

Still, even with these experimental schemes, the two companies have built up loyal customer bases.

Jaeden Sterling rides in a robo-taxi every day.

"I use them mostly for convenience and safety," the 18-year-old, who uses they/them pronouns, explained.

From the backseat of the Waymo, they watch the car's software detect other vehicles, pedestrians and cyclists in real time.

They said they feel more secure riding with a self-driving car than with other services such as Uber or Lyft.

"A lot of the time, (those) drivers feel rushed because their pay is based on the number of rides they're taking, so they may drive unsafe," Sterling said, adding that they see self-driving cars' frequent stops as a sign of the vehicles' caution.

Driverless cars' safety records are the main marketing argument for their manufactuers.

Waymo has had "no collisions involving pedestrians or cyclists" in "over a million miles of fully autonomous operations," the company told AFP, while "every vehicle-to-vehicle collision involved rule violations or dangerous behavior on the part of the human drivers."

But some local residents remain wary.

Cyrus Hall, a 43-year-old software engineer, worries about what could happen if a glitch shows up in a car's computer system.

He sees the vehicles' previous incidents as foreboding warnings that shouldn't be ignored.

"If they go to full service, and they scale (glitchy software) up, that's a much harder battle than making sure that we have a good regulatory framework in place now," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.