Sanctions Relief Won't Save Venezuela's Oil Industry, Analysts Say

In an agreement announced in Barbados last week, the Biden Administration temporarily scaled back Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) sanctions against Venezuela's oil industry in exchange for Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro committing to holding free and fair elections next year. The partial sanctions relief is scheduled to last six months, and then will be re-evaluated.

Despite the apparent economic opportunity associated with sanctions relief, some obstacles stand in the way of the revival of Venezuela's oil sector. Starting with political ones. A genuinely competitive election, which is the precondition for sanctions relief, isn't guaranteed.

The Maduro administration "is unlikely to allow itself to be defeated electorally," Ryan Berg, director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Americas Quarterly in May.

Any breach of the new agreement with the U.S. on Maduro's behalf will result in a full reinstatement of sanctions on Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state-owned oil company, and associated enterprises.

"We're in the presence of a new era for Venezuela," Maduro said on state TV Wednesday. "We are ready for a new era with the US, of respect, equality and advancement."

Opposition Candidate

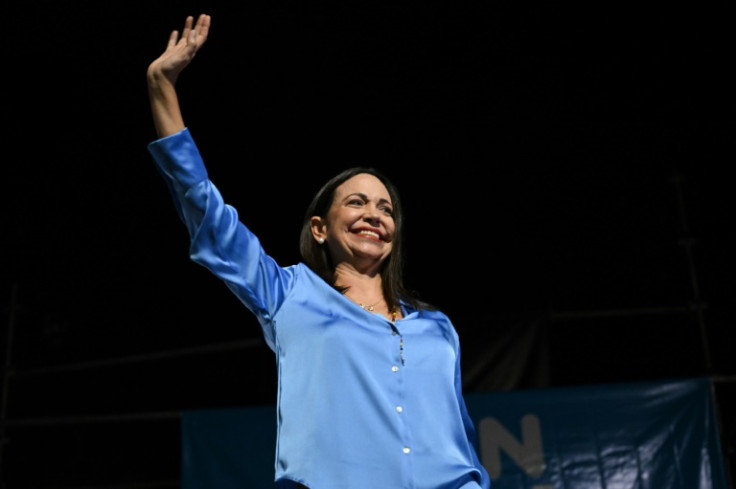

Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado resoundingly won Sunday's unsanctioned presidential primary, the first to be held in 11 years, raising expectations that Maduro could face a serious challenge in the 2024 election (the exact date of which has yet to be determined).

If a competitive election is indeed held and sanctions are removed, Machado has said that, as president, she plans to reinvigorate the country's oil sector by privatizing PDVSA. The company's production is still less than 50% of levels from before the oil shock of 2014/2015 and the imposition of U.S. sanctions in 2019.

"In 2024 we are going to win this presidential election, we are going to topple Nicolás Maduro and we are going to begin the reconstruction of our nation," Machado, 56, said in a public address Monday evening.

Machado is currently disqualified from running for office (a charge she contests) and Maduro's government has repeatedly lashed out against the prospect of international elections observers.

Low Oil Output

Additionally, Venezuela's oil infrastructure has endured a severe degree of neglect and underinvestment dating back to Hugo Chávez's presidency, limiting potential growth.

If all restrictions are lifted by 2025, Venezuela stands to add between 250,000 to 300,000 barrels/day in crude oil production, according to Francisco Monaldi, fellow in Latin American energy policy at Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy. Although that would be a 34% increase relative to current production, even in this scenario Venezuela would still produce less crude than its neighbor Brazil, and far less than the 2 million barrels/day PDVSA consistently pumped out before 2014.

"The likelihood that [sanctions relief] will materially impact the oil market is negligible," Ellen R. Wald, President of Transversal Consulting Group, told the Atlantic Council last week.

The Venezuelan state also still owes billions of dollars to international lenders, primarily China, in oil-backed debt, meaning that only around 40% of current production actually goes towards generating income. Even if Maduro were to leave office peacefully after a free election, his successor could not rely on oil revenue to nearly the same extent as previous governments.

The Biden Administration's easing of sanctions is the first of dozens of steps needed to resume some sense of normalcy in the Venezuelan economy—there is still a long road ahead. While it may be a sign of near-term hope for PDVSA, sanctions relief alone will not remedy the root causes of Venezuela's current crisis.

"What awaits us is an arduous road, we know it," María Corina Machado said Monday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.