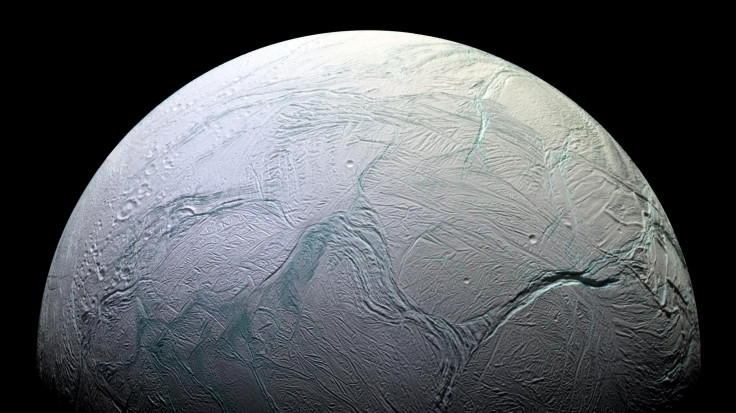

Saturn’s Enceladus Throwing Snowballs At Other Moons

Researchers have discovered that Saturn’s moon Enceladus is ejecting snow on its other neighboring moons Mimas and Tethys. The researchers believe the snow covering the surface of these moons is the reason for their high reflectivity.

For their study, researchers from the U.S. and France analyzed around 60 radar observations on Saturn’s moons, including data collected by NASA’s Cassini mission from 2004 to 2017. After going through the data, the researchers realized that the reflectivity of the moons increased over the years.

Upon closer inspection, the researchers discovered that the reason behind the moon’s high reflectivity is the snow falling on its surface. According to the researchers, water from Enceladus’ internal oceans is spewed out through geysers on the moon’s surface. The water then turns to ice as it leaves the moon.

The researchers noted that some of the water-ice particles fall and coat the surface of Enceladus while others reach Mimas and Tethys.

Dr. Alice Le Gall, a member of the researcher team, explained that the snow covering the moons have caused their reflectivity to increase.

“The super-bright radar signals that we observe require a snow cover that is at least a few tens of centimeters thick,” she said in a statement. “However, the composition alone cannot explain the extremely bright levels recorded.”

“Radar waves can penetrate transparent ice down to a few meters and therefore have more opportunities to bounce off buried structures,” she added. “The sub-surfaces of Saturn’s inner moons must contain highly efficient retro-reflectors that preferentially backscatter waves towards their source.”

In addition to the snow, researchers believe that there are other factors that contribute to the three moons’ reflectivity. Although the researchers are not yet sure what those factors are, they intend to continue analyzing the radar observations to understand the lunar events on Enceladus, Mimas and Tethys.

“So far, we don’t have a definitive answer,” Le Gall said. “However, understanding these radar measurements better will give us a clearer picture of the evolution of these moons and their interaction with Saturn’s unique ring environment. This could also be useful for future missions to land on the moons.”

The details of the researchers’ study were presented during this year’s EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.