School Accountability A Civil Rights Issue For Organizations Fighting New Elementary And Secondary Education Act

In a message to Congress before signing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act 50 years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson said full educational opportunity was a "national goal" because the country faced a "national problem." It was 1965, the height of the civil rights era, and gaps in achievement were pervasive. Johnson said he saw the law as a chance to bring better education to the millions of disadvantaged youth who needed it most.

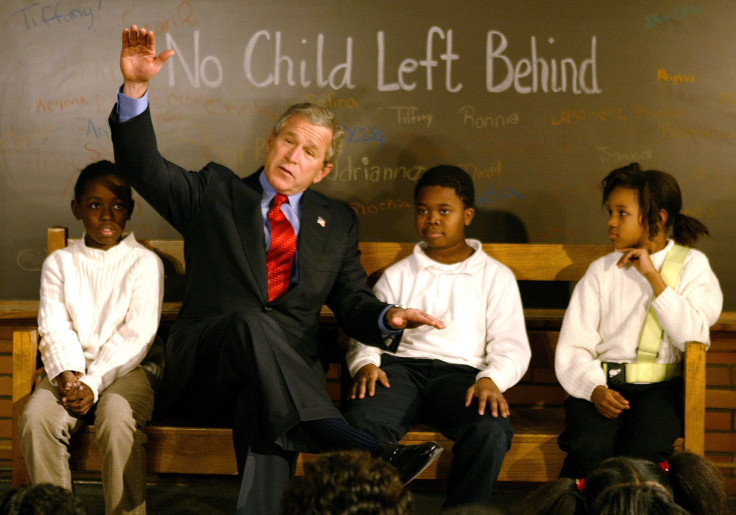

Now, as Congress works to reauthorize Johnson's policies, advocacy organizations worry that mission might be lost. This month, the House and Senate passed revamped versions of the education law aimed at reducing the amount of oversight its most recent iteration, the No Child Left Behind Act, gave the federal government. Both bills largely return the power for accountability, or required intervention in failing schools, to the states.

But student advocacy groups say they're concerned that shift would cause the updated law to stray too far from its original purpose. They say the federal government's role is critical in protecting certain minority subgroups of children -- specifically, those who are Hispanic, black, low-income, learning English or disabled.

"This is historic civil rights legislation, and we need to keep those federal accountability measures strong," said Brent Wilkes, the national executive director for the League of United Latin American Citizens, a Hispanic organization based in Washington, D.C. "We just don't trust certain states to do the right thing for minority populations."

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that in 2013, 86 percent of white eighth graders scored at or above the basic achievement level. About 68 percent of Hispanic eighth graders and 61 percent of black students scored the same, compared with 40 percent of disabled students and 30 percent of English-language learners.

No Child Left Behind, the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act under President George W. Bush, included provisions forcing states to identify repeatedly under-performing schools and intervene to help their students. The law prodded states to give the schools more resources and start enrichment programs, but the new bills back away from this. If the House and Senate bills become law, states would develop their own accountability systems and interventions, Politico reported.

This is a problem because there is no guarantee that states – dozens of which are run by Republican legislatures and governors -- will take action when students don’t perform well, Wilkes said. In the past, he added, some states' older populations may have opted to decrease investments in public education because they felt uncomfortable funding a school system that catered to a growing population of minority students. Wilkes pointed to California and Utah's fluctuating per-pupil spending as examples.

"We’re going from a robust accountability system to one that basically rolls the clock back and means that schools can completely fail our African-American and Latino students and still get a check mark,” he said. “We need to have a system that works for everyone, and not just for a privileged group of students.”

Wilkes' group and 37 organizations signed a letter Tuesday supporting an amendment from Democratic Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Cory Booker of New Jersey and Chris Murphy of Connecticut that would have required states to give extra support to any public school in the bottom 5 percent in the state, where 67 percent or fewer students graduate on time, or where low-income, disabled, minority or English-learning students don't meet state standards.

When that amendment was shot down, a smaller coalition issued another letter urging senators to oppose the bill entirely. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, NAACP, National Urban League, Southern Poverty Law Center joined with others to demand lawmakers "keep the commitment of the original ESEA to help the most vulnerable students.”

"This is really about equity," said James H. Wendorf, executive director of the National Center for Learning Disabilities in New York City. "It's about making sure that all students are understood, their needs are addressed, their academic achievement is documented, and that teachers can do what they do best."

The legislators behind the bill don't disagree that the new law has to cater to minority students -- just on how to do it. Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tennessee, said earlier this month that too many schools have failed too many kids for too long. But he said the federal government shouldn't be in charge of changing that.

"The national school board -- as I call it -- which has been created over the last 10 years as we move more and more responsibility from states to Washington, D.C., has created a backlash. It has made it harder to have higher standards. It has made it harder to evaluate teachers," Alexander said. "It has showed conclusively that the better path to higher standards, better teaching, and accountability is through the states and not through Washington."

But civil rights leaders insist the federal government is best suited to close the achievement gap. No Child Left Behind's accountability rules were partly responsible for the 16 percentage-point rise in the graduation rates of students with disabilities between 2001 and 2013, said National Disability Rights Network public policy analyst Amanda Lowe, who is based out of Washington, D.C. Without accountability safeguards, vulnerable students could get lost in the system, she said.

“They ensure that states are doing what they’re supposed to be doing,” Lowe said.

Phillip Lovell, the vice president for policy and advocacy for comprehensive high school reform at the Alliance for Excellent Education in Washington, D.C., said that the federal government shouldn't necessarily set what form school interventions take -- only that they must exist. States and districts should be able to tailor their extra resources to fit the specific needs of each school, whether that's curbing chronic absenteeism, starting intensive reading programs, or something else, he said.

But unless the bills get stricter, Lovell said, graduation rates and achievement will stagnate among underserved and minority children. "Students that are on a trajectory toward success will be just fine ... it's kids that need additional help that receive no guarantee of that support," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.