The Science Behind Facebook’s New Reactions: Why Mark Zuckerberg Said Nay To A ‘Yay’ Button

For the past seven years, the ubiquitous blue thumbs-up "like" symbol has been the core experience on Facebook. “Like us on Facebook” is displayed on millions of store windows, and media companies define success based on tallies of likes. It's an economy based on the like button, and more than a billion are sent each day.

But starting Wednesday that one-note emotion will be joined by five others chosen for their cross-cultural resonance around the globe: love, haha, wow, sad and angry. It's the biggest shift in the way Facebook works in years, and it will add an entirely new range of emotions users can express with one click or tap.

Called Facebook Reactions, the signals will change how Facebook's 1.59 billion users engage with the service. It will also bring a new range of signals to the advertisers and publishers, perhaps altering the tone of content and ads distributed there.

Users have long clamored for the equivalent of a "dislike" button, but until now the party line at Facebook has been a version of: If you don't like something, feel free to write a comment. And yet behind the scenes, Facebook was studying different reactions, bringing in outside academics to help distill a range of human emotions into a few emoticons that would give users more options while keeping the concept simple.

“We’ve been working on this for a while. It’s surprisingly complicated to make an interaction that you want to be that simple,” CEO Mark Zuckerberg said at a public town hall in Menlo Park, California, in September 2015, the first time Facebook publicly acknowledged it was working on a change.

The five new reactions are a result of about a year of research and testing by a team at Facebook dedicated to the new feature. “People come to Facebook to share all different things,” Sammi Krug, Facebook’s product manager for Reactions, said. “My college roommate got engaged. You’re so excited, and it didn’t feel right to just like that. I would have loved to love that.” Facebook Reactions hopes to allow people to more authentically react to posts, Krug said.

Commenting has been available on Facebook since even before the like button. The Reactions team studied the comments from Facebook users to see how people were reacting to posts on the social network. They also ran surveys and tapped psychology experts to provide insight.

Dacher Keltner, a 52-year-old father of two daughters, doesn’t use Facebook. But as founder and director of the University of California Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, he has worked with Facebook on several projects that required the expertise of a psychologist who specializes in social communication.

For instance, Keltner has presented to teams at Facebook’s headquarters on his research in the social functions of emotion. He has also consulted on previous major product updates such as the breakup tool, suicide prevention tools, the legacy issue and stickers. He also has worked with Google and with Disney’s Pixar for the film “Inside Out.”

Facebook first reached out to Keltner about Reactions in the spring of 2015. “They said that they’re trying to figure out: How do we react to other people producing information globally? They had the like button, but it’s broad and limited,” Keltner said.

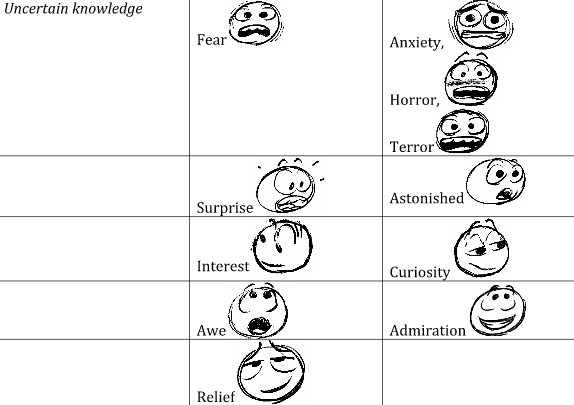

And so Keltner’s team at Berkeley drafted and shared an initial set of insights that included a map of human emotions as well as sketches. “It really mattered that the emoticons be scientifically faithful and capture what we really look like,” Keltner said.

Facebook consulted with them a few times before they began executing their own designs. They followed up for feedback after the initial designs were done. And after the global tests, Facebook shared thoughts on whether to not include the “yay” because it was not understood by all markets.

“Something that Mark pushed us really hard on, which was awesome, was making sure that the reactions we are using are very universally understood. It’s not just applicably available to one culture but really very much that this is made for the global community of Facebook,” Krug said.

And so out went yay despite a push by the Berkeley team. For Keltner, he wanted the network to offer as many choices as possible. Yet the Facebook product team said it needed to be limited — at least for now. “The Buddhists have this great concept of sympathetic joy. I wish they had it in, but it just didn’t happen. The best expression [of yay] has arms in the air,” Keltner said.

While a yay in emoji-speak might mean the blowing party horn, balloons or beer glasses clinking, Facebook chose to depict its emoji reactions, for the most part, with the human face. The like button as a thumbs-up and the love button as a heart are the two exceptions. “It’s all the human face. There aren’t as many possibilities for cultural confusion,” Keltner said.

Facebook uses the default color of yellow as seen in traditional emoticons. There are no diverse Facebook Reactions yet, despite the public outcry about such options for emoji by Unicode Consortium. For now, Facebook is keeping it simple and the same to all users. “We talked with [the localization and internationalization teams] a lot. Will these faces be applicable to every country?” Krug said. “We needed to make sure we understand how this is being understood.”

Prior to the global release, Facebook conducted small tests of the product in seven countries: Spain, Ireland, Chile, Portugal, the Philippines, Japan and Colombia. Krug said these markets provided diversity in languages and cultures, as well as device breakdowns.

Facebook chose to provide one system worldwide. Wyatt Jenkins, VP Product at Optimizely, a company that provides A/B testing and works with Facebook’s developer tools, cautioned that sometimes personalization provides a better user experience. However, Facebook wanted to be consistent globally, and therefore it was key that it experimented.

“Testing, at its core, is really about being empathetic. It’s about providing the experience your users want to have — not the other experience you think they should,” Jenkins said in a statement. “There is a certain level of humility in this kind of decision-making.”

Many companies may not be able to afford such thorough testing, but with Facebook’s $17 billion in annual revenue and a community of nearly 2 billion around the globe, it makes sense to take time. “Up until today there was one way to express a certain feeling about content on Facebook,” said Jason Klein, CEO of ListenFirst, a social analytics system. “Reactions has the potential to make it infinitely better.”

ListenFirst works with hundreds of high-level chief marketing officers at Fortune 1000 companies, and for years it has provided sentiment analysis tools. For example, ListenFirst’s system can scan Facebook comments and analyze how many are positive.

However, Klein admitted that computers are not perfect. “That’s an imperfect sign. It’s complicated to understand human language through computers,” Klein said. “If you think about how most people use social media, to draft sentences and to create words takes work. Most users engage with social by clicking buttons.”

Now Facebook’s own system will provide an easy-to-understand breakdown of insights that can show whether people simply liked or chose to love a post.

This update extends from the average Facebook user to publishers and advertisers. Some advertisers aren’t interested. “The cynic in me says, it doesn't really matter to Facebook and its advertisers which emoji verb you choose. As long as it gets a Reaction, Facebook and its partners can measure it, report on it, charge for it,” Tim Ocock, executive technical director of VML London, wrote in Marketing Magazine this month.

But Reactions could affect how publishers prioritize content. For example, the Huffington Post in February 2015 released a global editorial strategy called What’s Working that shed more light on positive news. It was inspired partly because positive news tends to be more widely shared on social media. ‘‘You’re not as likely to share a story of a beheading, right? I mean, you’ll read it,” editor-in-chief Arianna Huffington told employees, according to the New York Times.

However, now readers on Facebook can quickly engage with such stories and can choose to respond angrily. Just like with a like button, that interaction sends a boost to the algorithm. So perhaps bad news will lead online.

“It puts another level of complexity around how marketers strategize around looking at Facebook. A marketer can’t develop strategies around specific clicks or actions,” ListenFirst's Klein said. “Facebook is a dynamic landscape, and the best marketers are aware how dynamic it is.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.