Scientists Discover Secret Behind Longevity Of Human Eggs; May Help Female Cancer Patients

KEY POINTS

- All the oocytes that a female requires are present in the ovaries at birth

- These oocytes stay dormant for decades in the female body with no damage

- The conclusion was reached by administering live imaging, proteomic, and biochemistry techniques.

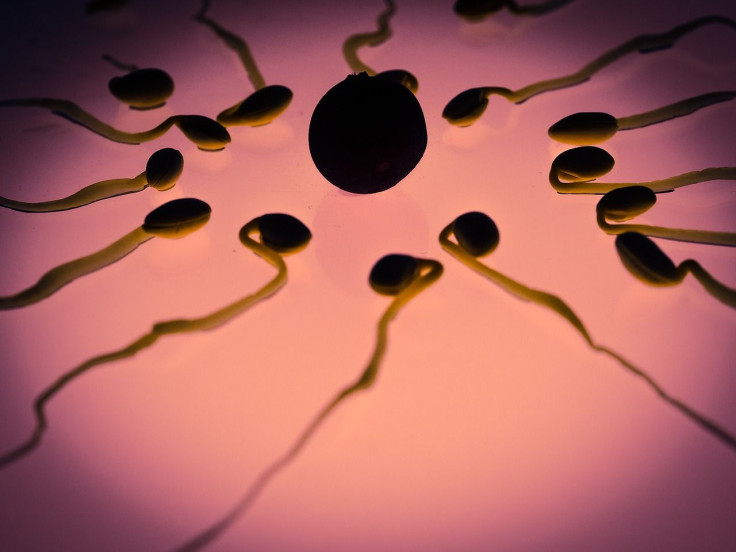

In a major breakthrough, scientists at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) have stumbled upon the secret to the longevity of human egg cells.

In the study, published in the journal Nature, it was found that immature human female egg cells called oocytes circumvent a crucial metabolic process that is pivotal in the energy generating process.

The cells, cleverly, omit the stage that releases reactive-oxygen species known to build up in the cells. These species damage DNA and can even lead to cell death.

This finding shed light on the unusually long dormancy human eggs go through.

“Brand New Paradigm” – Scientists Discover How Human Eggs Remain Healthy for Decades https://t.co/3oYJvwN4lg

— SciTechDaily (@SciTechDaily1) September 5, 2022

For the uninitiated, biology 101 is required.

In Humans, all the oocytes that a female requires are present at the time of birth in the ovaries. These oocytes, formed during fetal development, go through different stages of maturation. When the female hits puberty, each month an oocyte matures and is released by the ovaries.

These oocytes stay dormant for decades in the female body with practically no damage and retained functionality.

"Humans are born with all the supply of egg cells they have in life. As humans are also the longest-lived terrestrial mammal, egg cells have to maintain pristine conditions while avoiding decades of wear-and-tear. We show this problem is solved by skipping a fundamental metabolic reaction that is also the main source of damage to the cell. As a long-term maintenance strategy, it's like putting batteries on standby mode. This represents a brand-new paradigm never before seen in animal cells," Dr. Aida Rodriguez, first author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the CRG, said.

Scientists reached the conclusion by administering live imaging, proteomic, and biochemistry techniques.

The powerhouse of the cell, mitochondria, makes use of alternative metabolic pathways of energy production. This is something unseen in other types of animal cells.

It all comes down to an enzyme called complex I, which acts as a 'gatekeeper' that spurs the energy production process in mitochondria. This protein is omnipresent in all organisms ranging from yeast to blue whales. However, its absence in human oocytes is bewildering. The only other species known to showcase this absence in its cells is the parasitic plant mistletoe.

The authors further posit in their study that this revelation also explains why some women with complex I-related mitochondrial conditions like Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy have seemingly no effect on their fertility in comparison to women afflicted with other mitochondrial diseases.

Most importantly, the study's findings may help safeguard the egg reservoir of cancer patients in the future.

"Complex I inhibitors have previously been proposed as a cancer treatment. If these inhibitors show promise in future studies, they could potentially target cancerous cells while sparing oocytes," Dr. Elvan Böke, senior author of the study and Group Leader in the Cell & Developmental Biology program at the CRG, noted.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.